By Mohammad Sajjad

The Champaran Satyagraha (1917) occupies significance in the history of India’s anti-colonial struggle because of many reasons. One, it was Gandhi’s most spectacular and first experiment of non-violent Satyagraha in India; two, Bihar’s prioritized engagement with “regional patriotism” to become a separate province from the Bengal kept the reach of the Congress very limited in Bihar till Gandhi visited Champaran to intervene into the inhuman oppression to which the peasantry was subjected by the European planters. The indomitable peasant resistance however started manifesting more visibly since 1860s.

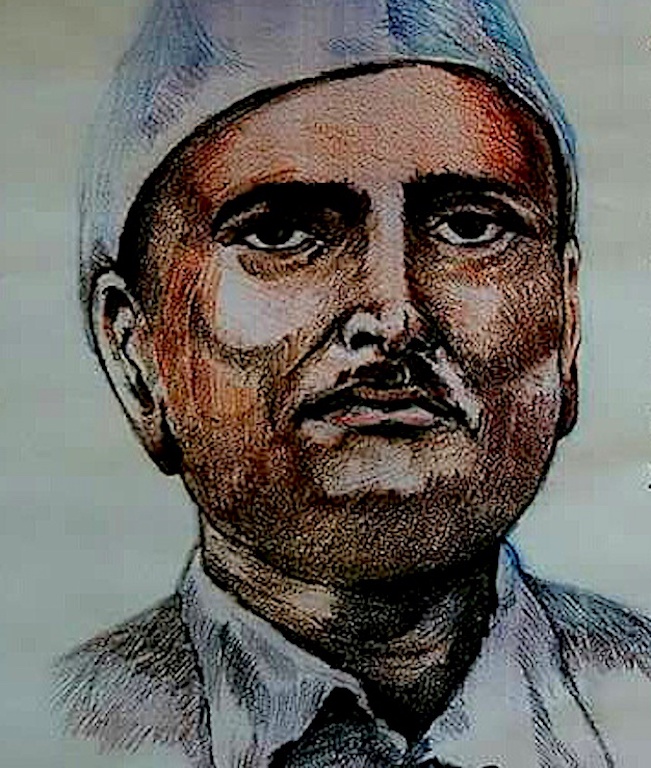

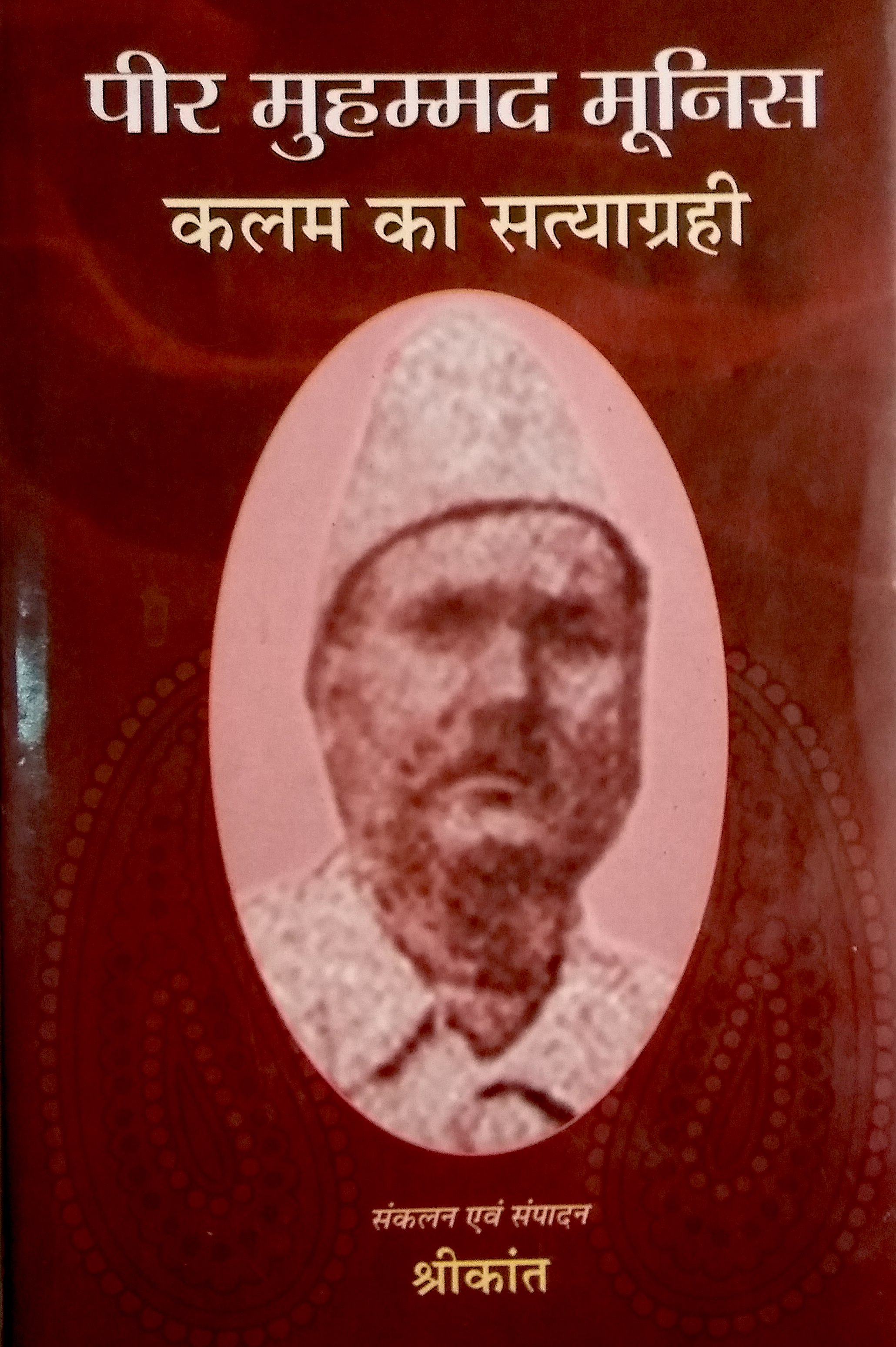

The scholars like Jacques Pouchepadass, Girish Mishra (1978), Razi Ahmad (1987) and few others have paid adequate academic attention to the issue. Still, the name of Pir Md. Ansari ‘Munis’ (1882-1949) remained much less known (except for the passing mention in such works). Hats off to Shrikant, a Patna–based journalist working with the Hindi daily Hindustan, (and co-author of two major, well-researched Hindi language academic books on contemporary Bihar), who delved into archival documents and the much scattered newspaper files to bring Munis’ profound roles into the popular and academic domain. This essay draws substantially upon Shrikant’s Hindi booklet, Pir Mohammad Munis: Qalam Ka Satyagrahi (Patna: Gandhi Sangrahalaya, 2000. Note: This useful book has got some proof-errors and inadequate, unprofessional referencing. One hopes, its revised edition will take care of all these).

Razi Ahmad’s work (1987) tells us that in the first wave of the Champaran peasant movement (1867-77), which was sticking more to legalities, one Meer Enayat Kareem of the village Siswa Ajgurreah, besides many others, had represented the ryots’ grievances to the local authorities and also to the Lt. Governor of Bengal, W. Gray, praying to appoint a Commission of Enquiry into the causes of peasant discontentment. In the second significant wave of the peasant protest in Champaran (1907-09), which was defiant and violent too, one Shaikh Gulab (1858-1943) of the village Chand Barwah and Shaikh Rajab Ali of the village Kala Barwah had supported the cause of ryots asking them not to grow indigo and to assault the planters if they forced them to grow indigo. Shaikh Gulab was tried on charges of unlawful assembly, arson, loot, and causing fatal attacks upon the planters and their property; the agitators were united in their opposition to the [European] planters irrespective of caste, creed, and religion. The Muslims took oath of loyalty with the Quran in their hands; the Hindus did so in the presence of their idols, cows, and under the sacred Pipal trees. It was widely believed that the reign of the English was over, and the leaders collected fund to fight the factory owners, which in their eyes, represented the British raj.

Much before the advent of Gandhi on the Champaran scene, Peer Md. Munis had played a very important and significant role as a local correspondent of the Hindi weekly, later daily, Pratap (Kanpur) edited by Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi (1890-1931).

Munis was a fearless journalist, and creative writer in Hindi literature, one of the founders of the Bihar Hindi Sahitya Sammelan (founded in Sonepur in 1919; and President of its 15th session, 1937, Arrah; his presidential address was reported in the Indian Nation, 25 December 1937). For his relentless efforts at exposing the horrific sufferings of the Champaran peasantry at the hands of the European planters, he was dismissed (1915?) from the services of teaching in the Bettiah Raj High English School, even though many such exposes were made by Munis in Pratap (Hindi weekly, Kanpur, later daily, edited by Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi, 1890-1931) with pseudonyms. It was through his essays/reports in Pratap that the horrific tales of Champaran became known to the world at large, and narrated eye witness account of those horrific tales. Munis is considered as the founder of fearless anti-colonial Hindi journalism in Bihar. The colonial dossiers referred to him as “dangerous”, and “notorious”, and “bitter” man writing “doubtful literature”. Munis was a correspondent for Pratap; he also wrote stories for children in Baalak, Hindi monthly edited by Rambriksha Benipuri (1899-1968), and published his patriotic poems in Hindi monthly, Gyanshakti, Gorakhpur (launched in 1915 it continued till 1935. See Arjun Tiwari, Swatantrata Aandolan aur Hindi Patrakaarita. Varanasi: BHU).

In Champaran, some sadhus used to distribute leaflets (of the reports/columns published in Pratap). The Shikarpur police and the Motihari police had seized such leaflets in February 1916. Besides, he was also on the editorial board of Desh launched and edited by Dr. Rajendra Prasad.

Munis had also written, “A History of Champaran”, the manuscript of which was with one of his comrades and a teacher in a Bettiah school, Harivansh Sahay, whose death made the manuscript traceless (probably in 1960s). Munis had also collected his newspaper columns, stories, etc., to publish its compilation in a volume; it was sent to the “Pustak Bhandar”, Darbhanga for publication, but these were destroyed in the massively devastative earthquake of 15 January 1934.

Usually, the text-books as well as the reference books, mention the role of Raj Kumar Shukla who invited Gandhi to intervene into the Champaran issue. The fact is that even the first letter written to Gandhi by Shukla was drafted by Munis. Apprising Gandhi of the miseries of Champaran Peasantry, Munis wrote, “Our sad tale is much worse than what you and your comrades have suffered in South Africa”. Shukla’s visit to the Lucknow session of the Congress (1916) to apprise Gandhi of the Champaran issue was the brain child of the peasant leaders, Shaikh Gulab and Munis, etc. When Gandhi visited Champaran, he made it a point to meet Munis’ mother, and met her on 23 April 1917. After Gandhi’s intervention, despite the theoretical abolition of the tinkathiya system, the peasantry continued to suffer at the hands of the European indigo planters; Munis then started, “Raiyati Sabha”. For which Munis further earned the colonial wrath, and in a falsely implicated case of June 1918 he was sentenced to be imprisoned in September 1918 and was put behind bars for six months besides some financial punitive fines (See Pratap, 30 September 1918). The Bettiah’s Sub-Divisional Officer, W. H. Lewis, in his letter to the Tirhut Commissioner, called him a ‘connecting link between the raiyat and the educated class’. (Pol. Spl. 1511/1917, Pt.II). In his essay, “Champaran Mein Phir Nadirshahi”, Munis protested against extraction of tax by the planter in the name of purchasing motor for a new born son of the planter. He subjected the Tehsildars and Jamadars of the Lauriya Kothi, as also the Court of Wards etc., to criticism for extortions.

In 1930 he was imprisoned in the Patna Camp jail for three months for his participation in the Salt Satyagraha of the Civil Disobedience Movement (Ashraf Qadri, 1992; Qadri lists many types of taxes extracted from the raiyats). In 1937 he provided leadership to the sugarcane producers protesting against the intermediaries who were pocketing bulk of the income accrued from this (KW 14/34, Report of the Commissioner, Tirhut, Muzaffarpur; The Searchlight, 29 December 1937). He addressed the public rally of the Harijan employees of the Bettiah municipality who were on strike protesting against few issues (The Searchlight, 19 December 1937). He was also elected member of the Champaran Zila Parishad (District Board) on the Congress ticket, and became President, Bettiah Local Board, from which he resigned and subsequently jumped into the Individual Civil Disobedience Movement.

His presidential address in the 15th session of the Bihar Hindi Sahitya Sammelan (24 December 1937, Arrah) reported in the Indian Nation, 25 Decemebr 1937) reveals that he was against sanskritised Hindi (panditon ki bhasha) and urged upon to make it simple so that it could be made popular (aam jan ki bhasha); he proposed to form “Ramayan Mandalis” for this purpose. In his address he welcomed the government decision to open a new department of rural development and he hoped that its newly appointed commissioner Prajapati Mishra and the education minister (Syed Mahmud) would undertake development works as well as would make efforts towards popularizing Hindi, in which he promised that the Sahitya Sammelan would extend all possible cooperation. He also proposed that the rural primary schools should be involved in popularizing Hindi on large scale. He also praised the creditworthy works done by Chhabinath Pandey (this Hindu Mahasabha leader has published his autobiography Apni Baat) for strengthening the Bihar Hindi Sahitya Sammelan. He also acknowledged the Muslim contributions in development of Hindi language and literature, viz., Amir Khusrau, Kabeer Jayasi, Raheem, Mubarak, Ras Khan, Nazeer, Meer, Zahur Bakhsh, etc. He also took stock of the development of Hindi literature and periodicals in Bihar; acknowledged the roles of the weeklies like Navashakti, Yogi, Pataliputra, Jivan, and Vibhakar; he was sad about absence of appreciable monthlies except Baalak (Laheria Sarai); he appreciated Sahitya, the quarterly journal of the Sahitya Sammelan.

Munis was strong advocate of “Hindustani”, simple Hindi with word-stock and diction from local languages/dialects; and refused to consider Hindi and Urdu as two separate languages. Various presidential addresses of the Bihar Hindi Sahitya Sammelan since 1919 generously acknowledge the contributions of Munis in strengthening it.

His essays and creative writings:

“Shart Bandhi Ghulami Ke Virudh Kharhey ho Jaao”,Pratap, 6 September, 1915

“Prarthana”, Ek Dukhi Aatma, Letter to Editor, Pratap, 17 February 1916

“Champaran Mein Atyachar”, Pratap, 28 February 1916

“Champaran Mein Andher, by Dukhi, Pratap, 13 March 1916

“Bihar Sarkar Ka Ek Anuchit Karya”, Pratap, 3 April 1916

“Champaran Ki Durdasha”, by Dukhi Hridaya, Pratap, 16 April 1917.

“Champaran Mein Phir Atyachar”, Pratap, 4 August 1919

“Champaran Mein Karmveer Gandhi Ka Aagaman”,Pratap, 30 April 1917

“Champaran Mein Mahatma Gandhi”, Pratap, 7, 14, 28 May 1917

“Champaran Mein Tinkathiya Pratha”, Pratap, 21 May; 4, 11, 18 June 1917.

“Hindu-Muslim Ekta”,

“Misr [Egypt] mein Parivartan”

“Mazhar-ul-haq Se Baat Cheet”, Pratap, 11 October 1920

“Champaran Mein Phir Nadirshahi”, by Dukhi Aatma,Pratap, 30 August 1920

Munis translated Tota Ram Sanadhya’s Hindi memoir, “Fiji Dvip Mein Merey 21 Varsh” into Urdu. This memoir had inspired many creative pieces of Hindi literature like Maithili Sharan Gupt’s “Kisan”, Lakshman Singh Chauhan’s (husband of Subhadra Kumari Chauhan) drama “Quli Pratha”. Jayaprakash Naran was also much inspired by this memoir.

His Stories for Children published in Baalak:

“Mahabharat Ka Yudh Kshetra”, vol. 2, no. 8, year ?

“Aurangzeb Ki Veerta”

“Waqt Ki Barbaadi”, vol. 2, no. 9, year?

“Hazrat Muhammad Sahab”, vol. 3, no.1., year?

His Poems/Couplets:

●Ranj ki ghahiyan hain lekin shaadmaani hai mujhe

Qaum burhi hai magar josh-e-jawani hai mujhe

Naa-ummeedi se zyada kuchh kaamraani hai mujhe

●Laazim hai Hinduon ko tan man nisaar karna

Hindustan ko Rashk-e-Bagh-o-Bahaar karna

(used in his essay, “Hindu-Muslim Ekta”, written after the Shahabad riots, 1917)

●Ai qaum dekh teri haalat ko kya hua

Hairat hai aaina ki surat ko kya hua

Ham ko zaleel sust o majboor dekh kar

Pratap keh raha hai hamiyyat ko kya hua

Jis ne barhey barhon ke the chhakkey chhurha diye

Us shoor veer qaum ki surat ko kya hua

Ironically, this hero of freedom struggle spent a life of abject poverty; one of the founders of the Bihar Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Ramdhari Prasad, kept extending financial help to him till very last. Acharya Shivpujan Sahay, while writing on Munis, said, “Vidyarthi’s killing in the communal riots of Kanpur in 1931 was a terrible shock to Munis which he could never overcome, and then Sahay adds about Munis, “Having forgotten such an ideal litterateur and patriot the heartless people [of independent India] is immersed in its own luxury”. I am also intrigued why didn’t the Congress bank upon the leaders like Munis in the face of the Muslim League’s onslaught during 1938-46?

(Mohammad Sajjad is an Asstt. Prof. at Centre of Advanced Study (CAS) in History, Aligarh Muslim University.)