By Namrata Chaturvedi for TwoCircles.net

The nation-state India is increasingly being referred to as Bharat, and Hindu religion seems more aggressive than ever. People who think critically about these realities are criticised for being pseudo, escapists, bohemians, sickular and so on. In India, Hindu religion is the majority religion and the numbers have perhaps given certain people the misconception that more numbers mean more rights.

When I travel in public transport, when I share public spaces with fellow citizens of my country, I see many Hindus around me, many of them (especially young men) communicating aggression through their body language. In the behavior of most people around me, meaning more Hindus than practitioners of any other religion, I see very little, if any, compassion. Since we are concluding by numbers, I can disappointingly conclude that Hindus lack compassion.

In Hindu theology, all the schools of thought explore the idea of karunā (compassion) as the end of spiritual endaevour. At the final stage of fullness (purnata), argues Abhinavagupta, the individual consciousness recognizes its oneness with param siva and on account of the Ananda (happiness) that follows this state of fulfillment, every individual soul extends compassion to other souls. The other souls are seen as still being fettered in avidya (limited knowledge) and hence in need of love and compassion.

In Sanskrit poetics, the beginning of kavya (literature) is attributed to the famous kraunch episode in Valmiki’s life. It is believed that Valmiki, on seeing two birds in a state of sambhog (union) was deeply affected when a hunter’s arrow slay the male bird. The weeping of the female bird led to such a deep churning in Valmiki’s consciousness, that the sublime story of love and devotion- the Ramayana was inspired. Valmiki was a transformed man and he created a compelling story that has soka (grief) at its aesthetic and philosophic core. Bhavabhuti has rendered the Ramayana story in its essence of soka (in Uttararamcharita) and has referred to the karuna rasa (the compassionate) as the most supreme of all rasas.

It should hardly be needed to establish that compassion born of witnessing grief lies at the core of all theologies in the world. In Buddhism, karunā follows from a realization of the dukkha of others, while in Christianity, the suffering of Christ compels a believer to extend compassion unto others as a means of atonement. In the light of compassion, why is the behavior of the average Hindu so utterly devoid of karunā?

Clearly, this is because the over used and much abused words Hindu thought have been appropriated in ways that have created a complete disconnect with one’s philosophical history. To be able to understand myself as a Hindu, I feel the need to understand my philosophies (there are more kinds of philosophies than Advaita Vedanta!) I then feel the need to see my lived life in those terms because only then can I claim equality with other theologies in asserting my rights and priveleges.

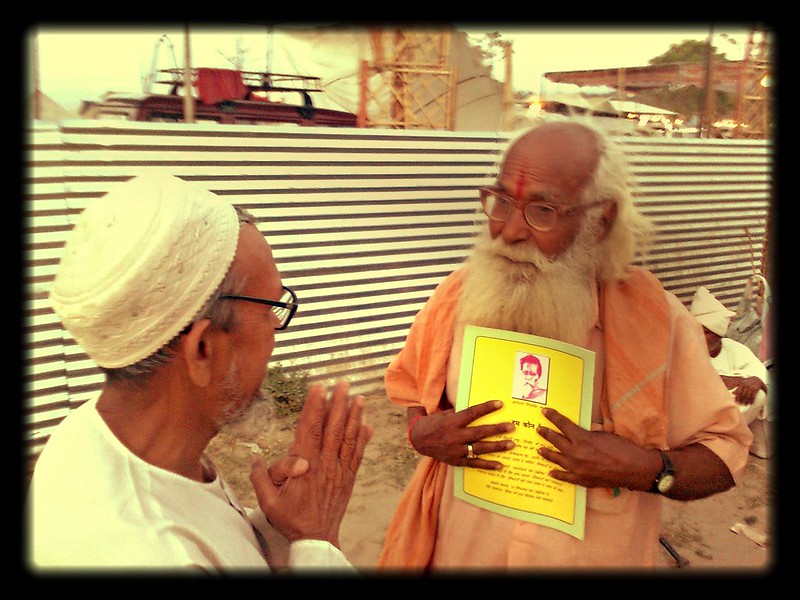

When I think of the nineteenth century, and come to thinkers like Dayanand Saraswati and the Shuddhi movement, I see the beginnings of this downfall. The interpretation and dissemination of Hindu philosophical ideas was left to certain individuals or organizations that severed the ties of an average Hindu with her theological foundations. These middle men emphasized on certain aspects of philosophies that made the average Hindu think that he is in some sort of an identity crisis and militant revivalism is the only answer. We stopped reading scholars and started believing swamis. Instead of worrying about the perceived persecution of Hindus, if we engage with the fantastic work of comparative theologians like Badrinath Chaturvedi, Anand Amaladass or Felix Wilfred, we will discover resonances of love and compassion across all theologies and will be better able to understand our own theology. Badrinath Chaturvedi has upheld Christ as the perfect embodiment of dharma and has nowhere claimed that Christ was Hindu.

In the 1990s, the principles of dharma and karunā that are so integral to any philosophy in Hindusim were reinterpreted as religion and foolishness, respectively. We all know how the concept of dharma, which actually means attributes of a particular entity, were disseminated to mean religion-mine versus yours. This has led to such grave errors, misjudgments and hatred amongst people that we have painfully witnessed. Yet, unlike Valmiki’s, our consciousnesses have not stirred towards karunā.

Let us look at the second concept. Every human consciousness is believed to be capable of compassion, and that includes the consciousness of one who calls himself Hindu too. So, when an old man comes and stands in the metro and a fit, young man continues to occupy his seat, what is the reason? Is it because he lacks compassion or is so wretched that he is incapable of ever feeling, let alone, extending it? I do not believe this. What I can understand from this behavior of his is that at some point, this most human impulse in him has been superseded by an indoctrinated idea. This idea is one of reaction, in thinking why should it be me, or us, always? This imagined persecution that many Hindus have been indoctrinated to believe makes them reactionary when they would want to be human. Just when that young man’s heart is willing to tell him to gracefully offer his seat to someone who needs it more than him, his mind that is not his own anymore, asks him why should he stand while many others like him are continuing to sit? Is it his responsibility alone to show kindness, sensitivity etc? The other day no one stood up for his uncle, so why should he bother? In lived reality, compassion is overcome by reaction, belief by cynicism.

So, when a Hindu feels the basic human urge to love another human being, he thinks members of other religions have been persecuting members of his in his own country, and he quickly erects impregnable walls of prejudice and bigotry around him, and becomes incapable of loving. The behavior of people makes me think that they fear being labeled a fool if they show kindness when at this time they should be sharpening their knives for an inevitable battle for their identity. Ironically, there is an identity crisis for the Hindus today, and it is most necessary that they revisit and reclaim their foundations of love and compassion and battle it out with doctrines that seek to reduce and mock humanity. There must be a reason why I do not perceive and will not be led into perceiving a threat to my identity as a Hindu. I have trained and challenged my mind to understand my dharma. I am sure you can do the same. Believe me, this independence gives more happiness than jumping to a master’s call.

—

Namrata Chaturvedi teaches in the Department of English, Zakir Husain Delhi College. Her area of research is comparative aesthetics and theology.