By Raqib Hameed Naik, TwoCircles.net

Pulwama: The year 2016 was extraordinary in Kashmir’s conflict-ridden history, and given the Valley’s past, that is a strong statement to make. What made last year so deadly was that along with men, women and young girls were also hit by lead pellets fired by security forces. As of now, there is no particular study done to find out, how many women were hit with pellets, but even conservative estimates would suggest a shockingly-high number. And Ifrah Shakoor is one of them.

Ifrah, who lost her father in a crossfire, waits in the kitchen in her house in Rahmoo, Pulwama. She is expecting her sister to bring “nun chai- Kashmiri tea”, which is served in the Valley during mornings and evenings. As she waits, Abdul Aziz, her 65-year-old grandfather joins her.

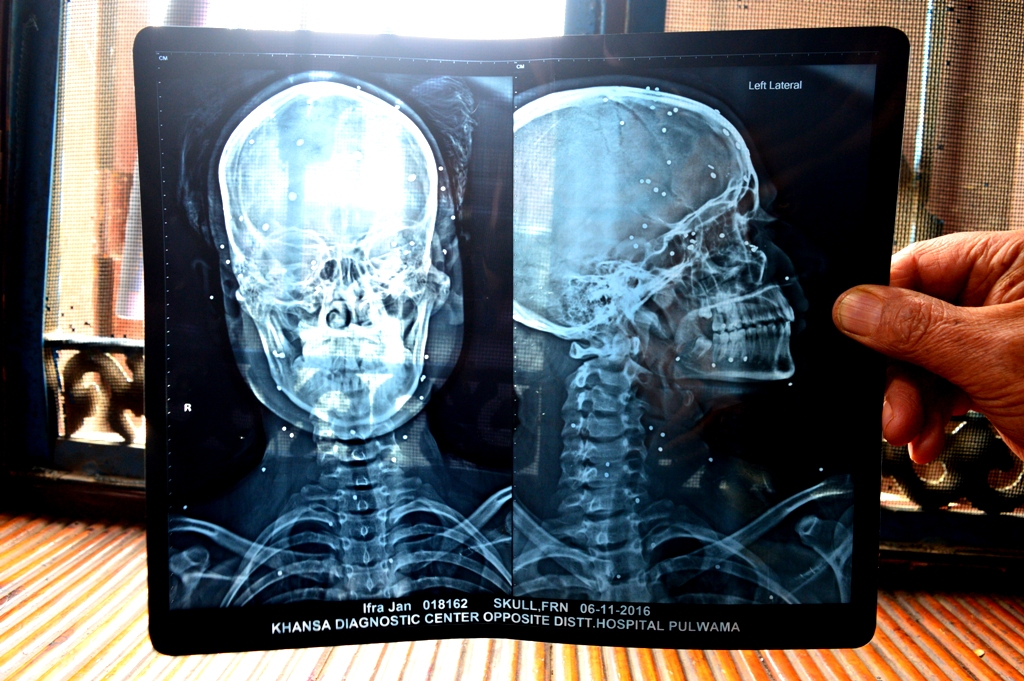

She instantly asks her grandfather, “Wen Kar chu hasptal tarun (When do we have to visit hospital)”, which he replied March 15. Ifrah was referring to Shri Maharaja Hari Singh (SMHS) hospital in Srinagar city, where she has gone through four eye surgeries after she was hit by pellets in October 2016.

On 31 October, a month before the government announced a mass promotion for different classes along with the 8th standard (Ifrah was in class 8) she was going through books back at home when security forces went berserk in her village.

The noises and sounds of pellet guns, tear gas shells and pepper gas rented the air leaving little Ifrah anxious and concerned about the safety of her younger brother, Yasir. Without giving a second thought, she ran toward the main gate, leaving books scattered on the rug, believing she will come back and put them into her school bag.

As she tried to set her foot outside the gate, she saw security forces marching on the road, firing tear gas and pellets at will. Realising that she was in a delicate spot, she tried to return to her house, but it was too late. A police man got hold of her hair and dragged her outside.

“I remember his face. He was a policeman. He pulled my hair and dragged me outside the gate and beat me up with sticks. I was shocked and cried out loud. Another policeman came and aimed his pellet guns at me and fired,” she recollects.

She lay flat on the ground with blood oozing from her chest, face and eyes. Neighbouring youths immediately bundled her into a car and drove straight to District hospital Pulwama from where she was referred to SMHS hospital in Srinagar city.

Her family couldn’t travel to Srinagar the same day due to the deteriorating law and order situation along the road leading to the city. They visited her the next morning.

“That w a s horrifying experience. I saw her lying in bed, moaning in pain. She was pellet-riddled from her chest to her face. You could see the holes in her face,” recalls Abdul Aziz.

As the pink walls inside the kitchen got gloomy with the details of 31stOctober, 11-year old Yasir Shakoor enters the room. Sitting beside his grandfather, he recalls his first meeting with her elder sister a week after she was hit by pellets in the hospital.

“When I saw her, I felt scared. I had seen boys with pellet injured but a girl; never. I tried to ask her if she was fine, but she couldn’t talk,” he recalls.

After finishing giving vivid details of his meeting, he plays a freedom song sung by a Punjabi rapper on his grandfather’s mobile phone. More than the sounds of utensils, the kitchen resonates with song lyrics, “Kashmir ki Azadi tak, Jang Jang, Jang Rahege.”

Ifrah remains sitting in a corner. Unmoved by what is happening around, she plays with the threads that have come out from the kitchen rug. Before she was hit in the eyes, Ifrah used to dedicate most of her time to studies. She was enrolled in 8th standard in Sheikh-ul-Alam educational Institute, Rahmoo.

Her grandfather was planning to send her to Srinagar city after she finished her 10th standard so as to let her pursue the dream of becoming a doctor. But pellets took away all her dreams.

“She has only 40 percent vision in right eye and a total blank left eye. Even though blind, she tried to read her books, but mostly, it was tears that rolled down her eyes. The doctors have advised her not to do anything,” says 35-year-old Fareeda Begum, Ifrah’s mother.

Even though Ifrah was treated at government hospital, the cost of medicines and other miscellaneous expenses prompted Abdul Aziz a small time farmer, to take debt from his friends. More than paying back the debt, Aziz is worried about the future of her granddaughter.

“In Kashmir, even if girls have no physical disability, it is hard to find groom for them. After hit by pellets, who will marry my Ifrah? ”asks Aziz intensely looking on the rug.

When asked who she blames for her present condition, Ifrah instantly names Mehbooba Mufti, the J&K Chief Minister. She says, “Mehbooba is responsible for it. Government was in her hand. She could have done anything to stop the pellet guns, but she didn’t.”

The younger Yasir jumps in the conversation and says, “Now, whatever is written in destiny will happen.”

“I will put in all my efforts to become a doctor and full the dreams of my sister,” he adds and ends the conversation with an optimistic note.

But for Ifrah, the life is divided between the darkness of life, and the dreaded operation theater.