By Raqib Hameed Naik, TwoCircles.net

As a group of children crosses the Handwara-Baramulla Highway at Watergam town in north Kashmir, Mushtaq Ahmed Dar, a mason curiously looks at them from the corner of an alley as they carry school bags of different colours; red, black, blue and brown, with straps hanging from the shoulders. The children gossip and giggle as they disappear in the morning fog, inside the woods leading to a tuition centre.

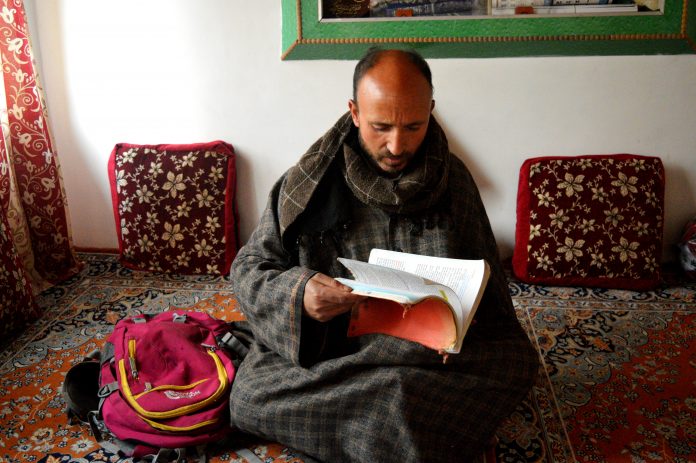

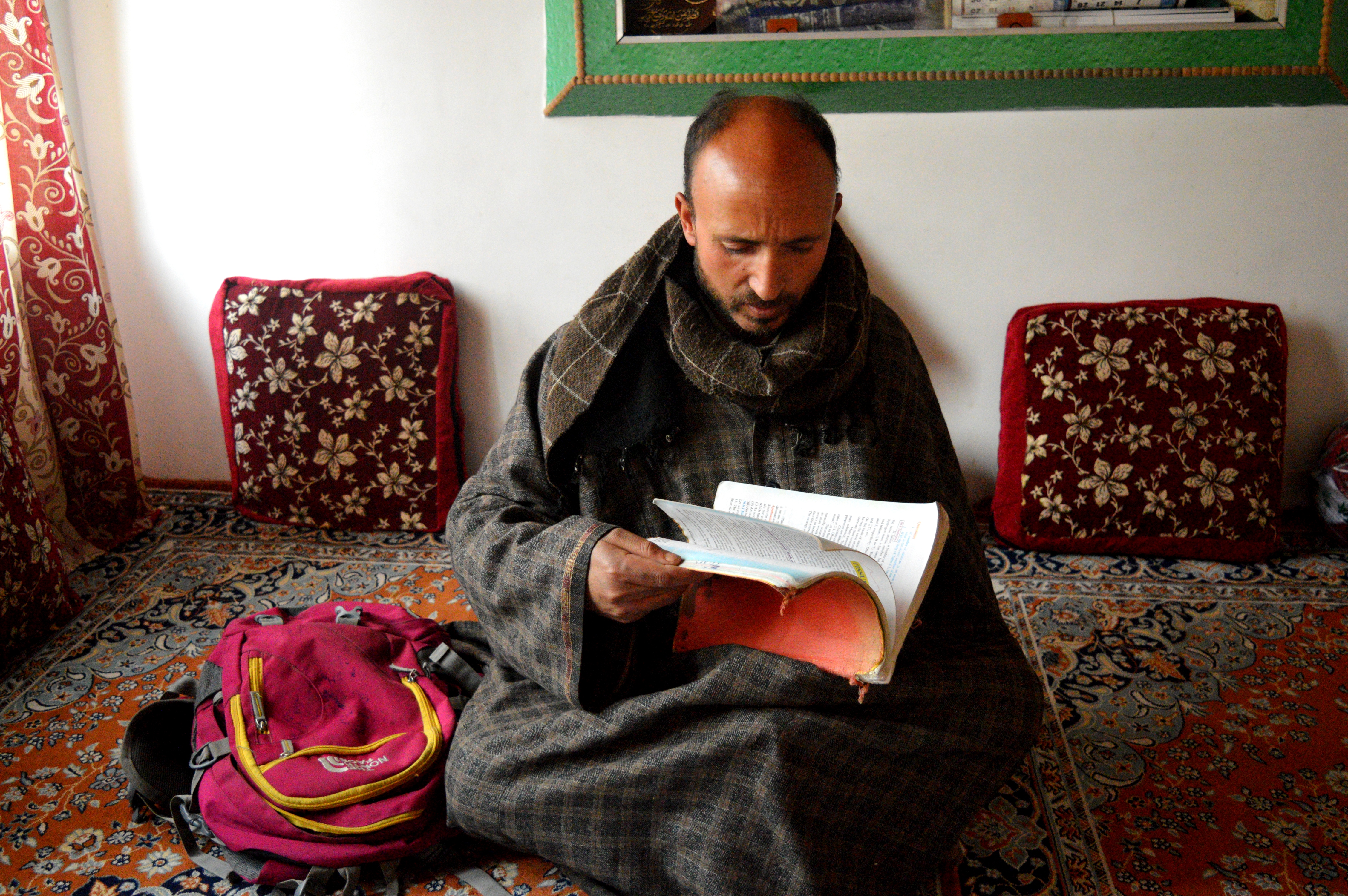

Forty-five-year-old Mushtaq, a thin, bald man wearing Phiran (a traditional Kashmiri gown) extending till feet and a muffler covering half his face grows restless as he loses sight of the children. He seems agitated. In the commotion, he rushes towards his house in Dangarpora locality, surrounded by poplar trees which have shed their leaves a month ago.

The moment he steps inside his single-storey modest house with faded walls and yellow windows, it is followed by a frantic search inside the rooms. The impression he creates is that of a person looking for something valuable for years.

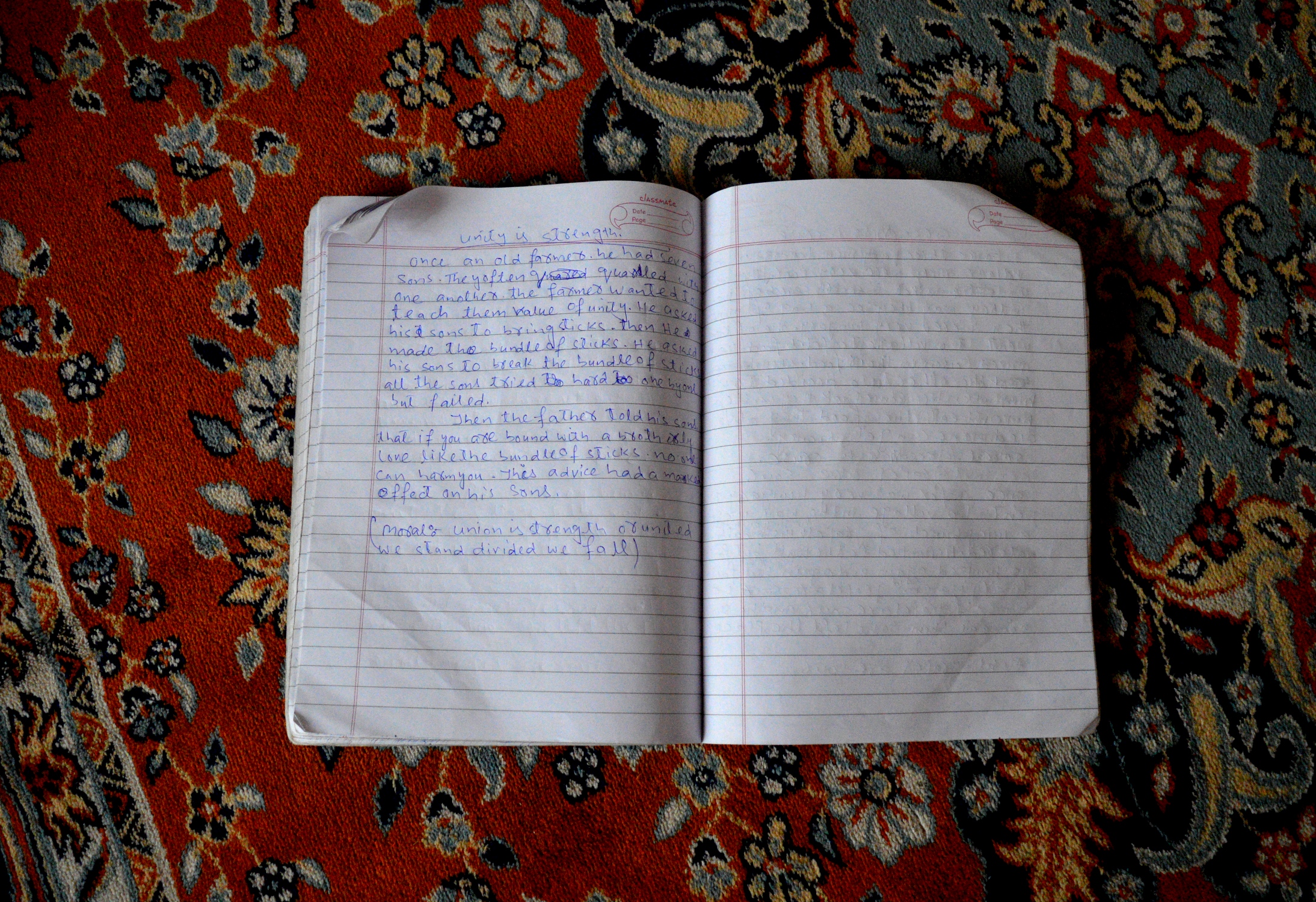

He peeps inside a wardrobe and pulls out a red school bag scribbled with different names, unzips and takes out a notebook, flipping the pages and stops at a page featuring essay ‘unity is strength’ written by Ubair Mushtaq Dar, 15 his eldest son who was studying in 9th standard on February 9, 2013 a day before he fell to the bullets of the security forces.

The fateful day of February 10

In February 2013, the Valley erupted in protests following the hanging of parliament attack convict Afzal Guru. As the protests intensified and spread across the valley, Ubair continued his life unperturbed and went to drop his three younger siblings to an Islamic seminary before he could head to purchase vegetables for dinner with a Rs 50 note gripped tightly in his right hand.

Three months before the fateful day, Mushtaq had fractured his neck in an accident and was bedridden for more than two months at Sher-e-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (SKIMS), Srinagar and asked to take bed rest for at least a month. Meanwhile, Ubair was religiously performing his new responsibilities from doing the household chores, buying groceries to dropping off his younger siblings at school.

“I was hospitalized and my wife was looking after me at the hospital. Back home Ubair was looking after his siblings,” recalls Mushtaq. “He treated them as if he were their mother. He baths them, washed their clothes and cooked meals for three months along with taking care of his own studies.”

The moment Ubair reached the Handawara-Baramulla national highway leading to the main Watergam market, he saw people being chased by the gun-wielding CRPF troopers flashing batons at the protestors. Panicked, and in a bid to save himself, he ran into an alley opening on an adjacent road leading to Sopore town. As he was walking alongside the road, a CRPF trooper spotted him and aimed his gun and pumped two bullets in his stomach leaving him in the pool of blood.

“I heard a lot of noise coming from outside. As I came out, people informed me that my son has been shot by the forces,” Mushtaq recalls the sequence of the fateful day.

“I ran towards the road, but he was already taken away by people and bundled into a car towards the hospital. I ran barefoot towards the primary health centre in the town, but he was not there,” he added.

Ubair was first taken to District hospital Baramulla from where he was referred to Sher-e-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (SKIMS) in Srinagar. He was profusely bleeding from his abdomen. On the way, he asked one of the attendants to make a call to his father.

“He spoke with me for at least two to three times and he kept on apologizing and repeating the words ‘Meh ditu nah dokhe keh’ (I didn’t betray you)”, Mushtaq recalls his last conversation with him. He died on his way before reaching the hospital. He still had the Rs 50 in his hand.

For Mushtaq, his death brought doom to his already shattered life.

“Every day, I used to come home by 5 pm and if I was late by even 10 minutes, he used to come out on the road and wait for me until I was home, but nobody waits for me now even though I keep waiting for somebody to come,” says Mushtaq in a choking voice.

Justice denied, Mushtaq treated like the accused

Two days after he was laid to rest, a government official visited him to hand over a cheque of Rs 1 lakh which Mushtaq rejected. “I was mourning the death of my son and they came to fix the price for his death.”

It took the local police six months to file an FIR after the determined Mushtaq kept repeatedly visited the local police station and made the visit to the various police officers. In between, he was threatened by CRPF personnel and officers not to pursue the case.

In one such incident, while he was on his way to work, he was stopped by a CRPF officer who categorically told him not to pursue the case and look after his other son Jeelani Mushtaq now 15, indirectly threatening to harm to the family.

“They knew all about my family. They hounded me for months to force me into their submission. An officer even told me that we have raped women in Kunan Poshpura and nobody could do anything,” he said.

The case went to the district court, where he appeared for at least 34 times in quest of justice, only to find that no one from police or CRPF turning up for hearings even once. Fed up with the judicial system, he gave up the case.

“I asked the judge that I am being treated like a killer and made to come every time despite the accused not turning up to which judge told me bluntly to take this matter to some other court,” Mushtaq recalls an incident at a court. “I have now left everything on Allah because he understands my loss.”

Solace in school bag

Ubair’s mother Masooda Begum, 40, a homemaker, has since been put on psychiatric medication. Most of the time she confines herself inside a room and keeps gazing at his pictures, sometimes bursting in tears and sometimes just looking and recalling how he used to call her “Mauji” (mother) and take dishes out of her hands to wash them off.

“I have never passed through the road where he was shot dead,” she says.“I don’t even have the strength to even go and sit in the room where he used to study and sleep. His books, clothes are in the same condition as they were in 2013. Those pieces of papers and clothes are the only memories left with us,” she added.

The family has stopped attending marriages. “I don’t have the courage to see a groom because it reminds me of my martyr son who could have been a groom as well, if alive,” says Mushtaq.

He has now cut his days at work and stays at home most of the time and finds solace by just touching the school bag of his martyr son and flipping the pages of his notebook.

“His school bag and books make me feel as if he is here with me,” he adds.