By TCN News,

London: Minorities and indigenous peoples have been among the last to benefit from the rapid growth of Asia’s cities, according to Minority Rights Group International’s (MRG) annual report release on Thursday.

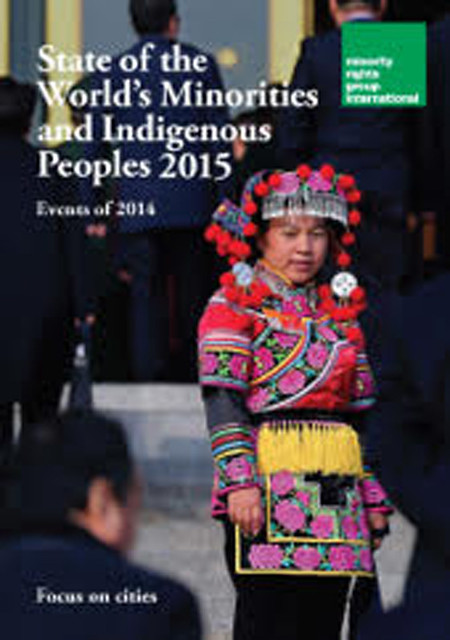

This year’s State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2015 focuses on cities and shows that a shift towards urban life has entrenched discrimination and fuelled insecurity for marginalized Asian communities, a release said here.

“Asia is home to many of the fastest urbanizing countries in the world, with a growing number of minorities and indigenous people migrating to cities. Many leave rural areas due to declining agricultural employment or displacement caused by armed conflict or development projects. But urban minorities and indigenous peoples often face isolation, inadequate housing and limited employment opportunities,” says the report.

“Minorities and indigenous peoples make up a significant portion of Asia’s urban populations, yet the benefits of economic growth have not been equally shared,” says Mark Lattimer, executive director at MRG. “In fact, the expansion of Asia’s cities has made some communities more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, while exacerbating existing inequalities and communal tensions.”

Minorities and indigenous peoples in Southeast Asia have been targets of evictions to make way for urban development projects, for example in Cambodia, or reduced to tourists attractions, such as in Thailand, the report said.

“Other urban minority populations have been openly discriminated against, including religious minorities in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, or violently targeted, like the Rohingya in Sittwe, Burma,” it pointed out.

In South Asia, the rapid expansion of cities has led to the growth of slums and informal settlements, often on the periphery of cities. In this context, dalits are particularly vulnerable to exploitative or unsanitary employment, such as manual scavenging, and represent one in five of urban slum dwellers in India. “Urban dalit women are subjected to additional layers of discrimination, including sexual violence and harassment,” it said.

In addition, many minority communities, such as Pakistan’s Christians and Shia, are increasingly being targeted for violent attacks in urban areas.

In East Asia, rapid urban growth is transforming China and leading to forcible resettlement, destruction of heritage and other impacts that have been felt especially acutely by Tibetan and Uyghur minorities. “For example in Kashgar, the state-led destruction of the city’s historic Uyghur architecture is a major contributor to unrest in the Xinjiang region,” the report said.

The pressures of integrating in urban areas can also pose a threat to the identities of minority and indigenous communities. For indigenous Australians some elements of traditional heritage have largely vanished. While 56 % of those in rural areas speak an indigenous language, this figure falls to just 1 % in urban areas.

Some 70 % of the world’s indigenous peoples reside in Asia, posing unique challenges as well as opportunities for its diverse urban populations. In Oceania, for example, traditional indigenous solutions to environmental hazards are being applied to the defence of urban areas from climate change. Similarly, in Baguio city in Philippines, indigenous women are earning a living through the application of traditional vermi-culture to solid waste recycling.

“Ensuring minority and indigenous peoples’ rights in urban areas benefits not only the communities themselves, but the entire urban population,” added Lattimer. “Their inclusion is, therefore, an essential element for any city seeking to become more socially just and sustainable in the long term.”

Excerpts on various India specific issues/themes from the report:

Displacement:

All over the world, development projects have taken place without the free, prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples, leading to mass displacements and women’s migration to the city. “It is estimated that in India approximately 26 million indigenous people have been displaced under the auspices of development projects since independence in 1947, many of which are hydroelectric projects. Without sufficient resettlement programmes in place, many end up in urban centres,” the report said.

Health and Sanitation:

A lack of regular access to clean water and sanitation facilities can pose direct threats to women’s health. Diseases that stem from a lack of sanitation, such as schistosomiasis, a parasitic disease that results in lesions to the urogenital tract, make women three times more vulnerable to HIV infection. Discrimination against Dalits in India manifests itself in unequal access to water and sanitation.

On the national level, it is estimated that 60 % of non-dalit women have access to adequate sanitation and water, whereas only 38 % of dalit women have adequate access. The same discrimination is manifested in urban slum dwellings, where dalits are over-represented. In one study from an urban slum in Chennai, 30.3 % of dalits had no access to adequate water supply and sanitation, compared to 20.8 % of non-dalits. A lack of hygienic options in informal settlements, particularly around menstruation time, causes unnecessary shame and threats to self-respect for women. As many urban informal settlements do not have access to clean water, due to gendered responsibilities, women must travel and queue for long hours to collect water.

Homeless:

In India, the drivers of homelessness are somewhat different and typically intertwined with the dynamics of migration from rural to urban areas, where extreme poverty combines with the pressure on migrant labour to support families back home. Again, minorities – principally dalits and poor Muslims – are disproportionately represented among the homeless. While data on homelessness, collected as part of the decennial census, does not disaggregate by religion or ethnicity, there is enough evidence that points to this imbalance.

In the context of urban poverty nationally, dalits and Muslims face higher levels of overcrowding and are concentrated disproportionately in the most marginalized urban areas, with an estimated 23 % of dalits and 19 % of Muslims based in slums, compared to 11 % of the majority community. There is also anecdotal evidence, as well as evidence in the form of qualitative accounts of civil society organizations working on homelessness issues, pointing to the fact that the homeless are largely made up of these two minorities.

While the situation of the homeless in urban areas generally is acute, the challenges experienced by those belonging to minorities are especially difficult. This is the case in Delhi, for example, the fastest growing metropolis in India and a magnet for labour from rural areas. Migrant labour in Delhi includes a large proportion of dalits and Muslims, mostly landless labourers from poor northern states such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal.

Concentrated around settlements with large Muslim populations or in the older parts of the city, again traditionally Muslim, they struggle to access housing and in many cases end up sleeping in the open streets. The absence of a permanent home means they are not even recorded for the purposes of social security schemes such as food rations or pensions. Violence on the streets, especially against homeless children and women, is known to be high.