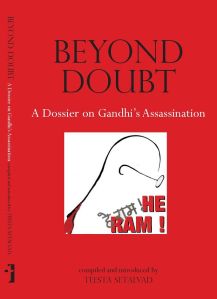

Teesta Setalvad has written a new book, Beyond Doubt: A Dossier on Gandhi’s Assassination on Mahatma Gandhi’s murder.

By Hillele.org,

Mumbai: Hansal Mehta, Tushar Gandhi and Kumar Ketkar came together in support of Teesta Setalvad’s book Beyond Doubt: A Dossier on Gandhi’s Assassination on Monday, March 16.

Teesta Setalvad in her short address to the guests and the Press on this occasion said, “Gandhi’s assassination was not a spontaneous act. There were five murder attempts made before Gandhi was actually killed. Godse was involved in two of the previous attempts. RSS’s visceral hatred towards Gandhi was because of his commitment to composite nationalism and his position on untouchability”.

Godse in characteristic RSS style lied blatantly when he claimed he killed Gandhi for the issue of Partition or the transfer of Rs 55 crores to Pakistan, the new book claims. Setalvad writes in the introduction of the Dossier: “The attempts on Gandhi’s life that began in 1934 were a response to the dominant political articulations of nationhood, caste, and economic and other democratic rights which directly challenged the idea of a hegemonistic and authoritarian Hindu Rashtra. In 1933, a year before the first attempt on his life, Gandhi had declared firm support to two Bills, one of which was against the abhorrent practice of untouchability.” RSS in its vicious propaganda never dares to mention the same she said.

In her introduction to the Dossier on Gandhi’s assassination Teesta Setalvad continues:

“The run up to Independence and, unfortunately, Partition, was the arena or battleground for fundamentally opposing notions of nationhood. While over a hundred years of sustained movements and mobilizations to throw off the British yoke came together in the united battle of all Indians against foreign rule, the early to mid-1900s saw the emergence of sectarian and communal definitions of Indian and Pakistani nationhood. With the birth of the Hindu Mahasabha, the Muslim league and the RSS, these movements – which on different occasions actually collaborated with the British – were in constant battle with the larger national movement. This volume also contains valuable references to how and when these right-wing protagonists collaborated with the colonial rulers. Parallel to Gandhi’s clear articulations about India as a secular state from the early 1930s, there was also the emergence of clear positions among the national leadership on the caste question as well as on the issue of the economic rights of large sections of Indians. Repeated use of the term ‘secular’ appears quite early in Gandhi’s writings and speeches of 1933.

A comprehensive understanding of the political context around this period of time is critical to locate the motivations that led to the systematically planned attempts on his life. As mentioned above, two proposed laws were before the Central legislature at the time, and one of these related to untouchability. Though much reviled in public discourse for his compromises on the caste question, Gandhi was clear that a ‘custom that is repugnant to the moral sense of mankind’ should be outlawed by a secular law. Such a practice, he said on 6 May 1933, ‘cannot and ought not to have the sanction of the law of a secular state’. In November 1933, he defended the Bill against the charge that it was an undue interference in religion, saying that there were many situations in which it was necessary for the state to interfere even with religion; only ‘undue’ interference ought to be avoided. In 1934, a year after his speech in support of the law against untouchability in the Central legislature, the first attempt on Gandhi’s life was made. At the time there was obviously no question of the grouse against him being the issue of Partition or the transfer of Rs 55 crores to Pakistan. It was the fact that Gandhi was a vocal proponent of India as a secular state, and, moreover, that he was at the forefront in striving for legal mechanisms to abolish discriminations based on religion, that made him unpopular among Hindutva fanatics.”

Teesta Setalvad’s introduction talks about the differences between Ambedkar and Gandhi-

“In 1925, Gandhi offered unqualified support to the Vykom Satyagraha, launched by the local leaders of Travancore (in present-day Kerala) who were protesting the ban on the entry of ‘untouchables’ on roads surrounding the Vykom temples. Through Young India Gandhi carried the message of the struggle of the satyagrahis to the rest of India until, finally, the matter began to be addressed by the national press. In March 1925 he went to Vykom and addressed public meetings there, besides holding discussions with leaders of the orthodoxy who were opposing the campaign. Finally, in January 1926, the Travancore government had to yield to the satyagrahis and announced the opening of roads around temples in Vykom to the ‘untouchables’. Gan-dhi pushed further, insisting that all public institutions, including temples, be opened to all. A few years later, on 20 September 1932, he undertook a fast unto death to implement the Communal Award. The Poona or Yervada Pact which came in its aftermath also gave a huge impetus to the movement for justice to the ‘untouchables’.

Differences between Ambedkar and Gandhi on this issue have been widely documented and analysed. Ambedkar’s valid criticism of the goals and priorities of the All India Untouchability league (later re-named the Harijan Sevak Sangh), which he thought were individualistic and reform-driven and

not aimed at the political and social emancipation of all Dalits, can be seen, among other places, in the correspondence between the two great leaders and thinkers. Even on the two Bills that came before the Central legislature in 1933, Ambedkar and Gandhi had detailed discussions, as well as differences.

The point, however, remains. Gandhi, who drew his moral force from his religion and wished to fundamentally reform and alter its approach to the structured inequity and indignity of caste, posed a great threat to those who would rather speak in the name of the Hindu faith, i.e. the fanatical fringe.”

Seniior Journalist Kumar Ketkar observed that “RSS is not an organization anymore. It is an ideology that is present in all sections of the society and across all political parties.”

(Courtesy: Syed Amir Abbas Rizvi (FB page))

Kumar Ketkar added that Modi’s victory was ten percent because of Development propaganda but mostly because of 2002 Gujrat. According to the Seniior Journalist RSS has managed to penetrate into some sections of Bengal also. While they may not emerge as the biggest party in West Bengal in next elections they may loom up menacingly as the second most important party, he said.

Mahatma Gandhi’s great-grandson Tushar Gandhi pointed out that “Teesta Setalvad’s forthcoming book which would include Kapur Commission report will be an important book to watch out for. Kapoor Commision Report has more evidence on the buildup to the assassination than the evidence that was available during the trial.”

In the 60s when some of the convicts of Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination case came out after serving their term the conspirators talked openly about the details of the conspiracy leading to the assassination. It is then that the Central Government set up Kapur Commission to further look into the details of the conspiracy.

A Dossier on Gandhi’s Assassination and stated in no uncertain terms that he was there to support Setalwad’s relentless work on secularism. He stated that the fabricated History of the Hindutva Brigade will destroy India. Hansal articulated strongly that he is an observer of the present day hate-mongering.

The program on Gandhi’s Assassination started with remembering Comrade Pansare and Gandhian leader Narayanbhai Desai. It was followed by a beautiful rendition of Vaishnava Jana Te by Sufi singer Ragini Rainu.

In her introduction in BEYOND DOUBT: A Dossier on Gandhi’s Assassination Teesta Setalvad writes-

“The assassination of Mahatma Gandhi on 30 January 1948 was a declaration of war and a statement

of intent. For the forces who conspired in the killing, the act was a declaration of war against the secular, democratic Indian state and all those who stood to affirm these principles, as well as an announcement of a lasting commitment to India as a ‘Hindu Rashtra’. It was also an act to signal the elimination of all that India’s national movement against imperialism stood for. Beyond Doubt is a dossier of historical and critical documents that aims to contextualize the politics, motivations and circumstances behind the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. Attempts to legitimize the act of killing and to celebrate the killers have re-doubled since May 2014, following the coming to power of the new regime in New Delhi. The time is right, therefore, to set the record straight.

The visceral hatred directed against Gandhi and the denigration of everything he stood for need to be recounted if we are to understand the political nature of that dastardly act. This book attempts to weave together archival documents from Government of India records relating to developments after the assassination, with translation of works in Marathi, Gujarati and Hindi de-constructing the ideology responsible for the political killing. While several of the documents have appeared before in issues ofCommunalism Combat, this compilation presents new material on the subject. The first English translation of Jagan Phadnis’s book, Mahatmyache Akher, forms part of the dossier, as do Y.D. Phadke’s analysis of attempts to legitimize Gandhi’s killing and Chunibhai Vaidya’s analysis of Pradeep Dalvi’s play on Godse. It also covers the recent controversy over the destruction of files relating to Gandhi’s assassination by Government of India.”