By Umair Azmi for TwoCircles.net

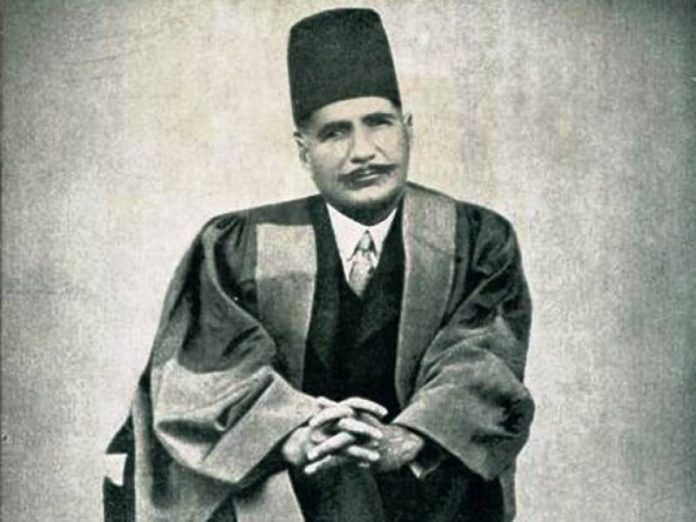

In a recent piece in the Indian Express (April 19, 2017), titled “Iqbal’s Wrong Turn”, public intellectual Pratap Bhanu Mehta sought a connection between the philosopher Dr. Muhammad Iqbal’s theory of tolerance and the killing of the Pakistani student, Mashal Khan. Mehta takes issue with the readings of others who see Iqbal’s theory of toleration as one that goes beyond liberal pieties, and argues that the religious approach has certain inherent limitations.

The pamphlet in question, “Islam and Ahmadism” was written in response to three articles written in the Modern Review by Jawaharlal Nehru in which, among other issues, he sought to know whether Dr. Iqbal considered the Turkish nationalist leader, Mustafa Kamal ‘Ataturk’, or the Turks in general to have abandoned Islam in light of their actions which included replacing the Arabic language of the Quran with Turkish in the Latin script. Nehru’s articles, in turn, were written in response to another pamphlet of Dr. Iqbal “Qadianis and Orthodox Muslims”. Dr. Iqbal refused to argue that they had abandoned Islam. Laying down the criteria for belonging to the Muslim community, he wrote:

“As long as a person is loyal to the two basic principles of Islam, i.e., the Unity of God and Finality of the Holy Prophet, not even the strictest mullah can turn him outside the pale of Islam even though his interpretations of the law or the text of the Quran are believed to be erroneous.”

In spite of these liberal criteria, Ahmadis, according to Dr. Iqbal fell outside the pale of Islam, for they denied the finality of the Holy Prophet. This, according to Mehta, is to cast Ahmadis out of toleration. “The lesson is that what matters is not the theory of toleration (which everyone professes) but the boundaries of toleration… Securing unity of a religious community through allegiance to a single principle, symbol or totem, has violence inherent in it.” It seems that for Mehta, an idea can be based on tolerance only if it includes everyone within its fold, or at least all those who claim to subscribe to it. Take two of the most popular ideologies of the day: liberalism and feminism. If Mohan Bhagwat were to claim that the RSS ideology is the epitome of liberalism (considering that the Sangh now claims to follow Gandhi as well as Ambedkar, this is no longer a totally outlandish suggestion), should we expect Mehta to acquiesce to it? Or if traditionalists who believe in gender-based division of roles (the female’s role being limited to household chores) claimed to be feminists, should we expect feminists to accept it without a murmur of protest? If liberals and feminists do protest, would Mehta be consistent and point them out as the narrow boundaries of toleration inherent in those ideologies? To take a more concrete actual example rather than an imagined one, will the republican in him consider North Korea to be a democratic republic, for the official name happens to be “Democratic People’s Republic of Korea”?

If a religion becomes intolerant on account of having an unalterable core, then consistency demands that all ideologies be considered equally intolerant. The only ideology that would be tolerant of all would be one that is devoid of all content, an ideology that is non-existent. The only community that would be tolerant would be one that is based on nothing.

Liberal tolerance and religious tolerance

Mehta argues that the question of toleration from the perspective of religion “has severe limitations.” Presumably, his idea of toleration would not suffer from these limitations. What is that idea? A newspaper article would not give enough space to elucidate a complete theory, but one does expect its application in other writings from the same author.

In his article titled “Jain lessons for Haryana” (The Indian Express, September 2, 2016), Mehta’s reflections on a nude monk’s address in the Haryana assembly, and the relation between dharma and politics are remarkable:

“But his presence also raised interesting cultural issues around pluralism, shame and the body. In a way, his presence was a riposte to liberals not because it was religious. But it did raise the question of how modern societies deal with really radical difference. How much are we seamlessly willing to accommodate cosmologies that are radically different, where monks are sky clad and inhabit public spaces? Or is modern society more disciplinary, and less pluralistic, than we suppose? We should not be so smug.”

It would be tempting to read this as an example of radical tolerance. But none of this reflection on the nature of modern pluralism and the limits of its accommodation can be found in “Not majority vs minority” (The Indian Express, September 6, 2016). Here, it was a question of communities not extending courtesies they demand to their members. “But all that liberalism requires to get started is extending the courtesy of the very same argument that communities use to keep other communities out, to individuals within them. The freedom from another community cannot be the freedom to oppress within.” The solution: laws based on liberalism should ride rough shod over personal laws.

One would think that an individual desiring freedom from community based laws could make use of the Special Marriage Act. But in his righteous liberal rage, why should Mehta be bothered with such trifles? With his repeated harping on the “un-representative” nature of the board, one might be forgiven for believing that the Constitution of India was written by a body chosen on the basis of universal adult franchise. Or perhaps “representation” is a criterion that is to be applied selectively.

The difference in Mehta’s attitude to “radical difference” among Jains and Muslims is remarkable, considering that the two articles were written within a week. While one demands reflection, the other demands only the most severe attack, and possibly, suppression by force. Is this due to a soft corner for Jainism, or due to intolerance for Islam? Either way, it is indicative of extreme personal prejudice and intolerance.

This is the limit of toleration that Mehta espouses- one where ideas are shoved down the throat under the garb of “individual rights, freedom and dignity”, for the only understanding that these concepts may have are those presented by liberalism. It seems those who do not subscribe to liberalism are perpetual infants, in need of the benevolent liberal masters forcing them for their own good. It is a telling illustration of a theory of toleration that is free of the “limitations” of a religious theory.

In contrast with liberal tolerance that enforces a monoculture is the theory borne out of religious considerations- where every community was allowed to live their lives as they deemed fit in accordance with their own civil laws. This is the practice that can be found in the earliest years of Islamic rule, as well as in the last of the caliphates, the Ottoman caliphate with its millet system. The tension regarding the limits of toleration were actions that were totally abhorrent to the Muslim psyche, such as incest and widow-burning, and even in these cases, the balance usually tilted in favour of the community’s own ethics rather than Muslim morality. Yet Mehta would have us understand that it is the religious perspective that has limitations.

The Islamic caliphates, especially the Umayyad caliphate of Andalusia produced remarkable cosmopolitan multi-cultural societies. The same may be true of the Byzantine Empire, with its Christian basis, and India as well. A totem of unity did not inhibit the flourishing of multiple cultures. But India, with its various forms of religion and no totem of unity, also produced one of the worst forms of structural violence in all of human history- the caste system. So much for the correlation between the insistence on religious unity and violence.

Iqbal’s complicity in anti-Ahmadi violence

As a postscript to his first pamphlet, “Qadianis and Orthodox Muslims”, Iqbal added:

“I understand that this statement has caused some misunderstanding in some quarters. It is thought that I have made a subtle suggestion to the Government to suppress the Qadiani movement by force. Nothing of the kind. I have made it clear that the policy of non-interference in religion is the only policy which can be adopted by the rulers of India. No other policy is possible. I confess, however, that to my mind this policy is harmful to the interests of religious communities; but there is no escape from it and those who suffer will have to safeguard their interests by suitable means. The best course for the rulers of India is, in my opinion, to declare the Qadianis a separate community. This will be perfectly consistent with the policy of the Qadianis themselves, and the Indian Muslim will tolerate them just as he tolerates other religions.”

Everyone but the rabid anti-Islamic troll knows that Muslim toleration of other religions does not imply lynching as happened with Mashal Khan. Yet, Pratap Bhanu Mehta charges Dr. Iqbal with being “complicit in intolerance”, the context being violence against Ahmadis in Pakistan.

If such tenuous connections are all that is required for the charge of complicity, dare we apply similar standards to our holy cows?

Consider this from Gandhi (cited by D.N.Jha in the introduction to “The Myth of the Holy Cow”): “Mother cow is in many ways better than the mother who gave us birth. Our mother gives us milk for a couple of years and then expects us to serve her when we grow up. Mother cow expects from us nothing but grass and grain. Our mother often falls ill and expects service from us. Mother cow rarely falls ill. Hers is an unbroken record of service which does not end with her death. Our mother when she dies means expenses of burial or cremation. Mother cow is as useful dead as when she is alive.”

Scores of such paeans to cow protection are attributed to the Mahatma. Should he then be held complicit in the murder of Akhlaq?

But Gandhi is no longer considered the faultless saint. The faultless sage of the age is Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. As opposed to Gandhi the sanatanist conservative, he is supposedly the supremely rational modern, unfettered by the chains of the past. What role does he play?

In the Constituent Assembly debates regarding what ultimately became Article 48, Muhammad Saadullah pleaded for the removal of the illogical connection between “animal husbandry on modern and scientific lines” and the prohibition of slaughter of cows, calves, etc. By ignoring this plea, and giving his stamp of approval to the directive principle, did not Ambedkar the rational endorse the “scientific” nature of gau-raksha? Must we then hold him complicit for atrocities in the name of the cow such as Una and numerous others?

Or is it only the Allamah who must meet a standard of innocence not demanded of others?

The contours of liberal toleration (at least the variety that Mehta upholds) appear to be very strange. There may be room for nudists, but there seems to be an allergy to anything Islamic (or does the allergy extend to all Abrahamic religions? Or non-Indic religions?) whether it be philosophy or civil law.

The author is an engineer, with a Masters degree in Computer Science, from the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore