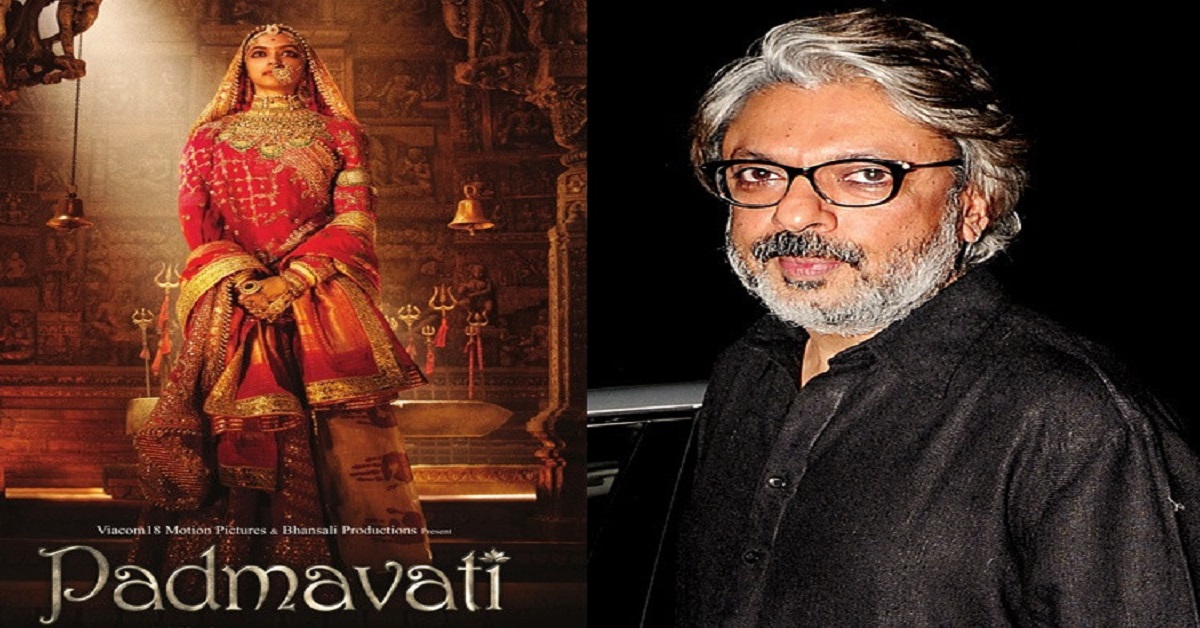

Facts and Fiction of Padmavat - the movie

By Misbahuddin Mirza:

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s recent movie – Padmaavat, is supposed to be based on the silly fictional tale written by Malik Muhammad Jayasi in the sixteenth century CE. The original fable romantically associates the mighty Sultan Alauddin Khilji - a highly accomplished actual twelfth century Muslim ruler with a fictional elderly Sri Lankan woman who already has a daughter of marriageable age (read: ready to be a grandmother).

It is common for film producers to take minor liberties to fit a story within the movie’s allotted run time. But, for a film producer to make wholesale changes to the story, and yet claim that his movie is based on a particular story is really strange. This is exactly what Bhansali has done. Bhansali has taken a ludicrous fable and then gone on to change it’s contents to suit his nefarious agenda – that is to create anti-Muslim sentiment among the Hindus. So, let us look at how Bhansali has distorted the original fable, mixed in references to certain historical events, and cooked up a cauldron of hate.

First things first: Hindu mythology categorizes women into six groups. The term “Padmini,” (Padmavati) or lotus women, is for the first category of women and is expressly reserved for very pale skinned women of extra ordinary beauty. Jayasi describes that the land of Sinhala (present day Sri Lanka) was full of Padminis. Sri Lankan women’s average height is 4’11”, and they do not quite meet the Hindu definition of a Padmini. It appears that Jayasi was confusing Sinhala with Sweden. In any event, since Padmini was a Sinhalese character, if Bhansali wanted to be accurate, why didn’t he use a shorter, darker Sinhalese actress to play the role of Padmini/ Padmavati? Because, if he had done so, the movie would have flopped in the Indian market.

In Jayasi’s fable, Ratansen does not accidentally discover Padmini when he is shot unintentionally by Bhansali’s trigger happy Padmini. Jayasi’s Padmini has a pet parrot – which, you guessed it, talks to people! Padmini refuses to marry a man of her father’s choice. Instead, she asks her pet parrot to find her a suitable husband. Padmini’s dad finds out that her daughter trusts a bird’s wisdom over his and places a hit on the parrot. When the soldiers take the parrot to the jungle to carry out the execution, the sly parrot manages to fly away. And it keeps flying from Sri Lanka, until, yes, you guessed right again, it reaches the forests of Chittoor in Northwest India. Now, the parrot has a lapse of judgement, and gets captured by Ratansen’s men. Once in Ratansen’s palace, the parrot decides that the already married Maharaval Ratansen would be the ideal husband for the young Padmini, back in Sri Lanka. So, the parrot starts describing Padmini’s beauty to Ratansen. How does Ratansen react when he hears the parrot’s description of Padmini?

Well, he reacts like every married man does when he hears a parrot describe a beautiful woman – he goes berserk, abandons his faithful wife Queen Nagmati, takes along 16,000 princes and starts on his odyssey to acquire Padmavati as a secondary queen – with the parrot as his navigator. Unfortunately, the parrot has apparently lost his GPS unit, or is a real sadist. Because, the parrot takes Ratansen and his entourage on a round the world sort of tour crossing numerous seas before reaching Sinhala. Once in Sinhala, in a Shiva temple, Ratansen decides to – yes, you are right again, burn himself – like committing the male version of Sati/ Jouhar. Notice Jayasi’s obsession with self-immolation, yet?

Everyone in Jayasi’s fable is eager to set themselves on fire at the drop of a hat. Before Rattansen can light the match, all the gods surround Ratansen’s pyre and attempt to brainstorm what was going on. One of the god tells that he can’t be of help as he himself had been struck by lightning. Well long story short, Padmini learns about Rattansen’s arrival, and is ecstatic – this is exactly what she had dreamt about since she was a little girl – get married to a middle-aged married man! So, on Vasant Panchami Padmini/ Padmavati comes to the Shiva temple to meet Ratansen.

So, why didn’t Bhansali show any of this in his movie? Why did he replace all this fascinating portion with a college-picnic-gone-awry type of boy-meets-girl-meeting between Padmavati and Ratansen? The answer is quite obvious, no one would have bought tickets to watch Jayasi’s silly tale. So, Bhansali changed it to look like a modern-teenage-romance-type of movie. Then why did he keep the fable’s name? Well, that would allow him to drag in and besmirch the name of the mighty Sultan’s name – although the Sultan ruled almost 300 years before Jayasi’s time, thus peddling hate against the Muslims.

The movie then conveniently skips all the years that Padmavati spends in Chittoor as wife number two bearing a child for Ratansen, then raising her child to marriageable age, while she gracefully ages, and becomes a middle-aged mother – ready to be a grandmother. For a young handsome and mighty emperor to entertain thoughts of marrying a Sri Lankan-would-be-grandmother, he would have to be blind, and probably deaf too.

The movie shows multi-lobbed arches holding up the Chittor palace. These elements are part of Islamic architecture developed by the Mughals. Multi-lobbed arches are not found in medieval Jain palaces. So, why did Bhansali indulge in wholesale inauthenticity by using Islamic architectural elements in a Jain palace of Chittor? Because, of the glamour value of Islamic architecture – read: box office/ ticket sales.

In the original fable, Jayasi describes Ratansen’s massive pre-battle assets, including enormous cannons on the fort’s turrets. Why didn’t Bhansali show the cannons on the forts? Because, cannons were not introduced into India until 300 years after Khilji’s reign, and the audience would have seen Jayasi’s naivety. Also, in Jayasi’s fable, while the Emperor was assailing the fortress, instead of using his military assets, Ratansen is engrossed in a song and dance extravaganza – the Indian version of Nero fiddling while Rome burnt. According to Jayasi, there was no hand to hand combat as Bhansali shows; instead, the fortress is sealed from the outside on all four sides using earthwork.

Eminent Indian historians like Irfan Habib, Prof K S Lal, and Prof Gauri Shankar Ojha - an expert on Rajasthan history, have categorically stated that Padmavati is a purely fictional character with absolutely no connection to history. Further, these historians explain that the legend of Padmini was started in 1540 – almost two and a half centuries after the Sultan’s time.

Amir Khusrau the court historian, who had accompanied the Sultan during the conquest of Chittor fort makes no mention of any Jauhar (Satti) being committed. Neither does the famous historian Ziauddin Barani mention any Jauhar/Sati in his history. The world has produced only a handful of military generals who were never defeated in battle - Alauddin Khilji is one of these exceptional military commanders.

Pundit Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime Minister of India in his book the Discovery of India categorized Sultan Alauddin Khilji as “Great.” Alauddin Khilji was an exceptionally talented ruler who saved India and Indians from utter devastation at the hands of the brutal Mongols. Then, he brought peace, and security to the capital city of Hazrat Delhi by wiping out the daily menace from the violent marauders, and bringing in market reforms to benefit all sections of the populace.

Bhansali’s movie doesn’t resemble Jayasi’s pubescent tale. His movie was expressly designed to make money by peddling hate against the Muslims.

Misbahuddin Mirza, M.S., P.E., is a licensed professional engineer, registered in the States of New York and New Jersey. He is the author of the iBook Illustrated Muslim Travel Guide to Jerusalem. He has written for major US and Indian publications.