Book review: Loknath Yashwant's Broken man might be too hard-hitting for 'Ghalib' fans

Mirza Ghalib is a celebrated figure in the vast world of poetry, and many times Ghalib produces a self-demolishing effect on one who is reading him. And this effect makes someone so vulnerable to Ghalib, that one does not dare to look at Ghalib critically even after loving his poetry. But reading the poetry of Loknath Yashwant, one gets the idea that how it is hard to absorb Ghalib in times when the revolution is a much-needed factor in poetry as well as in society.

“Ghalib Do you, or don’t you, wish us To awaken?”

- Extract from “Assadulla Khan Alias Mirza Ghalib”, Loknath Yashwant

Literature, especially poetry, has been at the forefront of Dalit movements across India. Poetry played a very special role in taking the Dalit movements from the roads up to the discussion tables. Poets like Namdev Dhasal and Dilip Chitre from Maharashtra played a key role in merging poetry with politics.

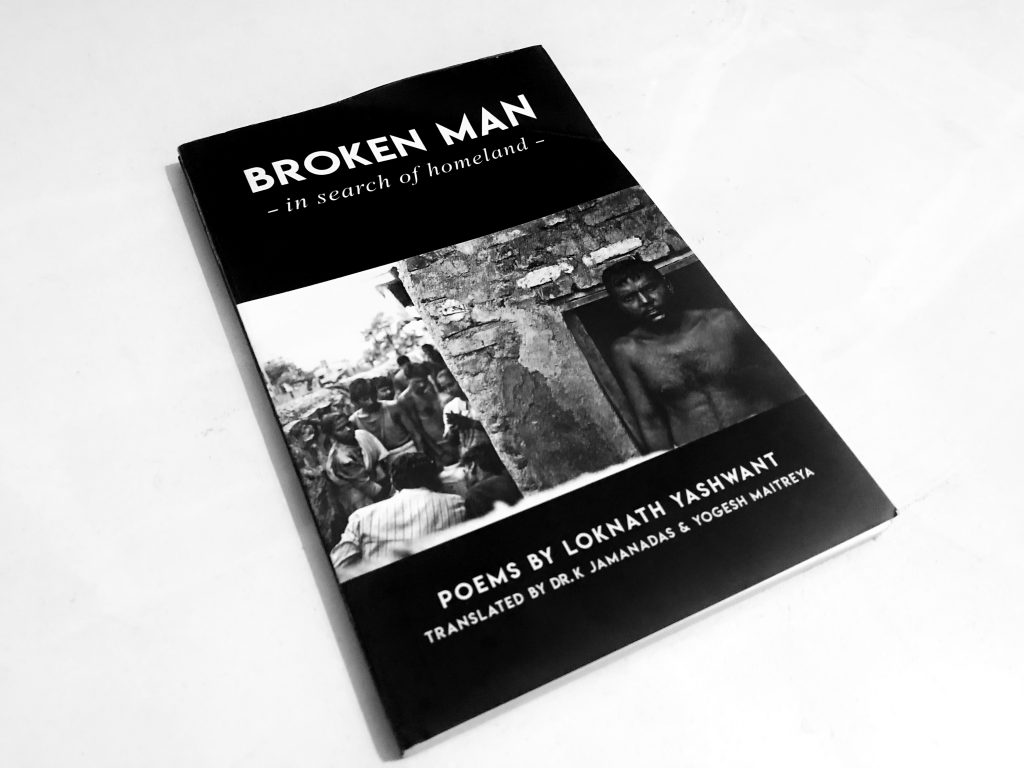

However, there have been various lost chapters and poets and Loknath Yashwant is one of them. His poems have now been translated into English by K Jamanadas and Yogesh Maitreya and the collection of the same is published by Panther's Paws Publications with the title “Broken Man: In Search of Homeland”.

The poems range from the more obvious voices that flourished under the anti-Caste revolution led by Bhimrao Ambedkar to more hidden and biting commentary over farmers’ suicides.

In the poem “Assadulla Khan Alias Mirza Ghalib”, cited above, Yashwant shows his love for the poetry of Ghalib, but at the same time he clears the air and asserts that Ghalib did not write about social inequality.

The protagonist in the poem visits his girlfriend, she is keeping her eye on his beard and no longer interested in poetry other than that of Ghalib.

“What a funny thing Since I explained your ghazals to her My beloved keeps on Gazing on my beard

”How is this love of your ghazals, Ghalib? My beloved is in no mood To listen to my poems”

He also describes his visit to Taj and writes,

“The hands that built the Taj Are bleeding I see them in my dreams Crying Ghalib, is there a ghazal of yours On the subject of Social inequality?”

The poetry of Ghalib keeps the poet disturbed and let him seek the answer from Urdu “awaangaard” if he would let the society awake or not?

There is one unique aspect to this collection of poetry. It highlights the discourse related to Dalit practice of Buddhism. In particular, Yashwanth critiques certain practices. Since Ambedkar accepted Buddhism in the year 1956 with about half a million Dalits-Bahujans, he also made it very clear that the existing form of Buddhism and practices under it have been introduced later by Buddhist monks and should not be practiced by Dalits. For example, several ideologues have asked why it is that Buddhist-Dalits do not perform long meditations, wear saffron-red clothes, or exercise Vipassana? One firm answer to these questions is that Ambedkar’s Dalit Buddhist movement, led to the absorption of a new kind of Buddhism,which included specific pragmatic and political principles that written in to the 22 vows given by Ambedkar himself during his conversion in 1956. Practices like Vipassana within Ambedkarite Buddhism can be optional and sometimes perceived as removed from practical daily life.

The poet here puts a sarcastic commentary over the school and practice of Vipasana by saying:

“You collected fat on your body You could not sit among higher ups Still you mixed with the lowers?”

It goes on:

“The thief in your mind Very, very crafty and sharp Does not spare you Constantly digging like a rodent That is why, you have no alternative Except Vipasana! There is nothing to be ashamed of”

And further:

“When death comes near The inactive person, in any case Always becomes religious While daydreaming You were not with the society Now is the time For dreams to get shattered Carry on with your Vipasana There is nothing to be ashamed of!”

And by writing this, Yashwant reminds me of Hindi poet GM Muktibodh who disowned the social comfort and elitism in his poems. What Loknath Yashwant writes is certainly not exactly comparable to any piece of work but Yashwant does make it a strong point in the discourse by simply stating that comfort is not the state of living or revolution. This he does simultaneous with his disregard for practices of Buddhism—like Vipasana of Goenka.

Through the poem “One Sentence”, Yashwant asserts that all the long dialogues of society, and multi-page essays and hours of debates are not really by or for the common men, because “I make my whole argument/ In one single sentence” . In his view, the demand to bring the equality in the society is not a thing on which debates should happen.

Yashwant reflects upon Kabir, a 15th century poet who disregarded every religion, class, and sect, to address the bigger problems of 20th and 21st centuries:

“How beautiful, how straight forward and joyous Life once was, Kabir These bullies made a mess of things Beneath our noses Futile it was, Kabir To impart peace, or love Through your Dohas”

Yashwant seems to have paid attention to every problem of what we call is an actual common man of the Indian society. He uses a brutal and a very focused metaphor to discuss the caste system:

“The butcher loves me a lot True, great love That’s why He has placed me At the very end”

There have been several questions over the godly treatment of Mahatma Gandhi as he was projected as an Avatar for Dalits-Bahujans by many(He used word “Harijan” which was disowned by the community). In his poem “Jotiba Pule”, Yashwant addresses the upper caste-dominated politics which established Mahatma Gandhi over actual Dalit leaders and annihilators.

“In the name of the Mahatma They set up vegetable stalls Sel brinjals, and cucumbers How did this become the order of day? And when? We were unaware!”

In another poem “Sub-caste”, Loknath Yashwant tried to portray the conflict and politics in the subject of sub-caste. The small poem goes as:

“The jailor slipped into a nap Carefree Because Of late, prisoners have started Keeping a watch on each other”

Through these verses he calls importance to the issue of unity between oppressed Castes and warns of oppressing oneself along the lines of sub-Castes

[caption id="attachment_427015" align="alignnone" width="400"] Loknath Yashwant[/caption]

Loknath Yashwant[/caption]

Yashwant also has a very interesting sarcastic tone in his writing. Yashwant writes “A Worker at the Farm” (not “The Farmer”, in an effort to note that farm laborers are often separate from and even more exploited than the farmers themselves) putting an imaginary prospect of life which could be seen in the context of suicides committed by the farmers. This is the powerful narrative produced here in this poem:

“I love this life so much I’ve just got one I live by the definition Of a maverick dreamer I do not commit suicide Like a farmer”

Yashwant’s many establishments subtly remind me of 1995 essay “Ur-Fascism” by Italian writer Umberto Eco in which he counted many traits of intolerance and resultant fascism. Yashwant’s poetry also reflects and talks about these same traits in the context of the subcontinent..

The collection “Broken Man” is a book on the struggle for power, about the anger of the people with a focus on the propaganda politics of India which gives rise to establishment.

While here is very little crying and complaints, there is one poem on complains In “The Complaint”, Yashwant writes: