The mask slips from Modi’s faltering image as he responds to a “viral apocalypse” of “unprecedented proportions” by silencing critics of his approach.

Pieter Friedrich, TwoCircles.net

“Destructive and anti-Bharat [India] forces in the society can take advantage of these circumstances to create an atmosphere of negativity and mistrust in the country,” warned Dattatreya Hosabale, second-in-command of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) paramilitary, as India suffers the world’s worst COVID-19 crisis.

The scale of the crisis is a hot topic — and a sore one for the RSS, the parent group of India’s ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) — as a horrified world weeps while a viral tsunami crashes over the country. “The country has descended into a tragedy of unprecedented proportions,” reported The Guardian on April 21. “COVID ravages India,” reported The New York Times on April 25.

Yet Hosabale, on April 24, seemed more concerned with “conspiracies of these destructive forces” and urging those “active on social media” to play a “positive role,” show “more restraint,” and be “vigilant.”

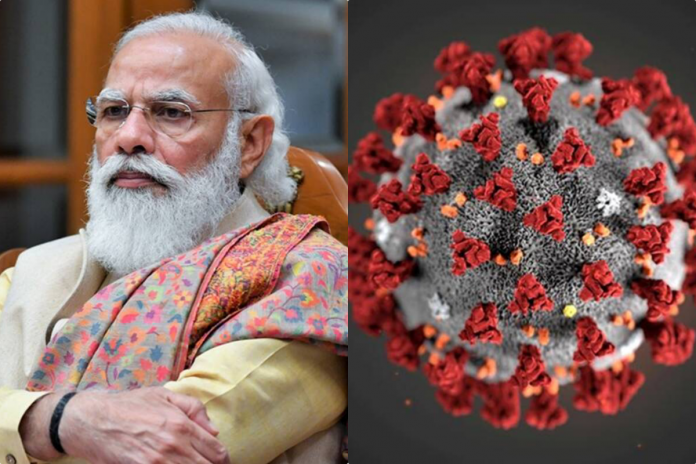

The RSS leader’s comments came as BJP Prime Minister Narendra Modi — a product of the paramilitary — faces criticism of unprecedented proportions over his perceived mishandling of the crisis. Failure to prepare. Overconfidence. Defiantly hosting political rallies internationally ridiculed as “super spreader” events. Such negative accusations threaten to spoil the positive atmosphere the RSS is trying to cultivate.

“There are less number of deaths in India compared to the US or Italy,” said Hosabale in May 2020. Praising Modi’s “direct interaction with the people,” he added, “However, every life is precious yet we managed to keep the numbers down.” Nearly six months later, RSS Chief Mohan Bhagwat applauded how “damage done by COVID-19 is relatively lesser in India as [the] country’s administration alerted people in advance.”

Hours before Modi put India under lockdown in March 2020, reported The Caravan, he “personally asked” 20 owners and editors of major media outlets to “publish inspiring and positive stories” about his response to the pandemic. He’s facing the 2021 surge with similar tactics. “India has a new strategy for fighting its COVID-19 crisis — asking Twitter to take down the criticism of the government,” reported New York Post on April 24.

On April 21, the Modi regime ordered Twitter to block Indian access to dozens of tweets. The tweets, said a BJP spokesperson, were “fake news that harms the country.”

My own tweet, among 55 censored, featured a photo of a woman sitting in the street breathing from an oxygen cylinder. “The reality of India under the Modi regime,” I wrote. “At least the healthcare is free?”

Today, news and social media around the world is flooded by reported shortages of ambulances, hospital beds, oxygen, plasma, and even wood to cremate the dead. The woman sitting on the street — her photograph captured in 2018 — was reportedly waiting for an ambulance that never came. Six months later, however, Modi unveiled the “Statue of Unity.” The world’s tallest statue came at a cost of $430 million.

The Indian American Muslim Council, which is one of the largest advocacy organization of Indian Muslims in the United States, was also censored for tweeting a Vice article about how the Modi regime allowed millions to gather for a religious festival in Uttarakhand. “As visuals from the festival emerged, social media users and journalists were quick to point out that while last year’s Tablighi Jamaat — an Islamic evangelical congregation — was called a ‘jihadi’ and ‘super spreader’ event, politicians and some mainstream media news channels have refrained from speaking against the Kumbh Mela,” reported the article.

Instead, Uttarkhand’s newly-appointed Chief Minister Tirath Singh Rawat (an RSS stalwart) argued, “Kumbh is at the bank of the River Ganga. Maa [Mother] Ganga’s blessings are there in the flow. So, there should be no corona.”

“Despite the severity of the health crisis, election rallies and religious congregations like the Kumbh Mela in Haridwar have continued, raising questions over the seriousness to tackle the spread of the deadly virus,” reported Firstpost. Meanwhile, as Modi campaigned for the BJP in West Bengal, he boasted, “I have never seen such crowds at a rally.” In response, state minister Moloy Ghatak tweeted, “When death bodies were burning, Nero was busy doing election rallies.”

Ghatak’s tweet was also censored.

Image management has always been the Modi regime’s greatest skill, and censorship is its preferred tool. The regime’s response to tweets criticizing its COVID response typifies its reaction to any opposition, dissent, or counter-narrative.

When a young farmer died during the Republic Day protests in January 2021, the regime slapped sedition charges on several prominent journalists for reporting allegations by the family that police shot their son. Twitter accounts critical of the regime have repeatedly had their tweets withheld in India or their accounts suspended, especially for commenting on issues like Kashmir or the ongoing farmers protest. After Amnesty International India published a field investigation documenting police “complicity and active participation” in the February 2020 Delhi Pogrom, the regime froze Amnesty India’s bank accounts, effectively shutting it down.

The broadest net was cast in the improbable Bhima Koregaon conspiracy case, a so-called “witch-hunt” which has ensnared 16 academics and activists, many of whom have now been jailed for years. “What is happening to me is not something unique happening to me alone,” said octogenarian Jesuit priest Stan Swamy in October 2020 as he became the latest accused to be arrested in the case. “It is a broader process that is taking place all over the country. We are all aware how prominent intellectuals, lawyers, writers, poets, activists, students, leaders, they are all put into jail because they have expressed their dissent or raised questions about the ruling powers of India.”

Writer and former professor Anand Teltumbde was arrested six months before Swamy. In 2018, amidst the first wave of arrests in the case, Teltumbde had remarked that the “current repression… reminds one of the fascist formations in Italy in the 1930s and Nazi ones in Germany in the 1940s.”

Even India’s Supreme Court, once upon a time, aired similarly harsh criticisms of Modi. In 2004, shortly after he first rose to political office, the Court labelled him a modern-day Nero. Modi, the Court argued, was “looking elsewhere when… innocent children and helpless women were burning” in the carnage that erupted days after Modi was appointed Chief Minister of Gujarat in 2002.

Although the Court may then have been beyond Modi’s reach, such was not the case for one whistleblower in the new Chief Minister’s administration.

BJP State Minister Haren Pandya stepped forward to claim that Modi sanctioned the three days of anti-Muslim violence which is today known to many as the 2002 Gujarat Pogrom. Pandya “gave sworn testimony about the riots, and also spoke to the newsweekly Outlook,” reported The New Yorker. In 2003, he was assassinated. “Modi’s shadow lies all over the Haren Pandya case,” claimed Indian journalist Vinod Jose. Pandya’s wife and father both termed it “a political murder.”

In 2005, a media sting caught pogrom participants (such as a BJP state legislator) bragging not only that Modi gave them “three days to do whatever we could” but that he also helped prevent their conviction. Their informal confessions appeared to corroborate Pandya’s allegations. It also seemed to confirm the Supreme Court’s earlier observation that “the modern-day ‘Neros’… were probably deliberating how the perpetrators of the crime can be protected.”

Watchdogs like Human Rights Watch blamed the violence on “militant groups that operate with impunity and under the patronage of the state,” naming the RSS and its subsidiaries as “the groups most directly responsible.” His reputation blemished, Modi soon became the only person ever banned from the US for “particularly severe violations of religious freedom.” So he set upon the monumental task of internationally whitewashing his tarnished image, rebranding himself as “NaMo.”

“Modi’s transformation over the past year from a regional, right-wing politician to a decisive leader with a clear development agenda, the one best suited to take India forward is nothing short of extraordinary,” reported Business Today in 2014. Not so long ago, the outlet added, he was viewed as “authoritarian, megalomaniac and communal.” Modi “carefully charted out” his transition “from a raging Hindu nationalist to India’s most popular prime ministerial candidate,” reported Business Standard.

According to marketing expert Dr Siddharth Shekhar Singh, the “huge investment” promised dividends for other vested interests. “The branding of Modi was a well-crafted strategy of the RSS and the BJP,” he wrote. “Not only can brand Modi sustain the BJP in power for a long time, but it can also help the RSS reposition itself.”

Now, as COVID spirals out of control, the Modi regime’s priority appears to be to keep doing what it does best: image management.

Yet the gleam of Brand Modi risks being dimmed by the shadow of stigma. People around the world are waking up and smelling the chai. Within India, millions are mad as hell and refusing to take it anymore. The nation has been in upheaval for nearly 18 months. The COVID crisis has brought events to a fever pitch.

Although the emerging pandemic gave Modi over a year which he could have spent preparing for what one journalist termed a “viral apocalypse,” he instead spent it laying symbolic foundations for the Hindu Nation which the RSS seeks to build.

At the pandemic’s outset, Modi had already faced months of relentless protest against his regime’s new Citizenship Amendment Act (which premises acquisition of Indian citizenship on religion). In March 2020, what remnants of the brutalized protests was left were swept aside by what the regime calls “the longest and strictest lockdown in the world.” While the RSS praised Modi’s COVID response and enjoyed the opportunity to begin assuming police-like duties, Modi assumed a ceremonial role to fulfil the decades-old ambitions of the BJP.

One of the Hindu nationalist party’s central goals was to establish a temple at a disputed site in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh. In the 1990s, Modi helped organize a nationwide campaign to remove a pre-existing mosque from the site. The campaign reached its climax when, after listening to speeches by RSS-BJP leaders, a mob tore the mosque down, paving the way for Modi to assume the mantle of a priest as he laid the foundation stone for the new temple on 5 August 2020.

The date was auspiciously chosen to coincide with the anniversary of another longstanding RSS-BJP demand — the 2019 annexation of Jammu and Kashmir, the only Muslim-majority state in a nation now ruled by Hindu nationalists.

“He travelled to Ayodhya in the middle of a raging pandemic to be the master of the groundbreaking ceremony of the temple, in spite of heading the government of a constitutionally secular country,” wrote peace and conflict researcher Dr Ashok Swain. “Modi does not anymore pretend even as the leader of a secular country. He sees himself and overtly acts like a king of a Hindu Kingdom.”

In December 2020, Modi again acted as both king and priest, performing prayers as he laid the foundation stone for a new parliament building in Delhi. “This is not the redesign of buildings, it is instead Modi’s way of placing himself at the centre and cementing his legacy as the maker of a new Hindu India,” wrote British sculptor Anish Kapoor. Architecture as propaganda, he noted, is often used “to give a good face to a fascist regime.”

Lately, the regime needs a facelift — and it’s lashing out at anyone who points out the obvious.

Even Rihanna. After the singer tweeted that people should talk about the Indian farmer’s protest, India’s Ministry of External Affairs issued a formal rebuke. “The temptation of sensationalist social media hashtags and comments, especially when resorted to by celebrities and others, is neither accurate nor responsible,” the ministry scolded.

Now the regime is scrambling to squash negative international newspaper coverage. “Arrogance, hyper-nationalism and bureaucratic incompetence have combined to create a crisis of epic proportions in India, with its crowd-loving PM basking while citizens suffocate,” reported The Australian on 25 April. A day later, India’s Embassy in Australia responded with a public letter denouncing the “baseless, malicious, and slanderous article” as “written only with the sole objective of undermining the universally acclaimed approach taken by the Government of India to fight against the deadly global pandemic.”

To suffocate dissent, Modi’s regime has locked up academics and activists, charged journalists with sedition, shuttered Amnesty International India, blocked critical social media, started a spat with a pop star, and harassed a foreign newspaper.

Now a BJP politician once called “Modi’s nearest political clone” is adopting a new tactic to stifle critics. Condemning people who report shortages of oxygen as “anti-social elements” who “spoil the atmosphere,” Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath declared that their property should be seized.

Superspreading censorship, however, may no longer help Modi mask his faltering image.

International scepticism is spreading. The harsh reality is now too extreme for even the most efficient of fascists to cover up. Meanwhile, in India, resolve is growing. “We are part of the process,” said Father Stan Swamy. “In a way, I am happy to be part of this process. I am not a silent spectator, but part of the game, and ready to pay the price whatever be it.”

As India gasps for air, however, countless innocents are paying a price forced upon them by a regime that values its iron grasp on power over the lives of the people.

Pieter Friedrich is a freelance journalist specializing in the analysis of South Asian affairs. He is the author of “Saffron Fascists: India’s Hindu Nationalist Rulers” and co-author of “Captivating the Simple-Hearted: A Struggle for Human Dignity in the Indian Subcontinent.”