Hana Vahab, TwoCircles.net

In the remote village of Hundi in Kupwara, the northernmost district of Kashmir, 15-year-old Wajid dreams of clearing prestigious Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) examination to become a civil servant. Despite the limitations imposed by his circumstances, he sits with his family of six in the small front yard of their home, taking on the role of a responsible adult.

There is no electricity in their home, as in many others here. According to the Power Department’s curtailment schedule, electricity was supposed to be restored by 1 p.m. after a two-hour shutdown. But as the clock ticks on, the lights remain off. This is not an isolated case. Villages across Kupwara, including Zirhama, Gujjar Pati, Laaderwan and Marhama, are also grappling with daily power outages – often for hours on end.

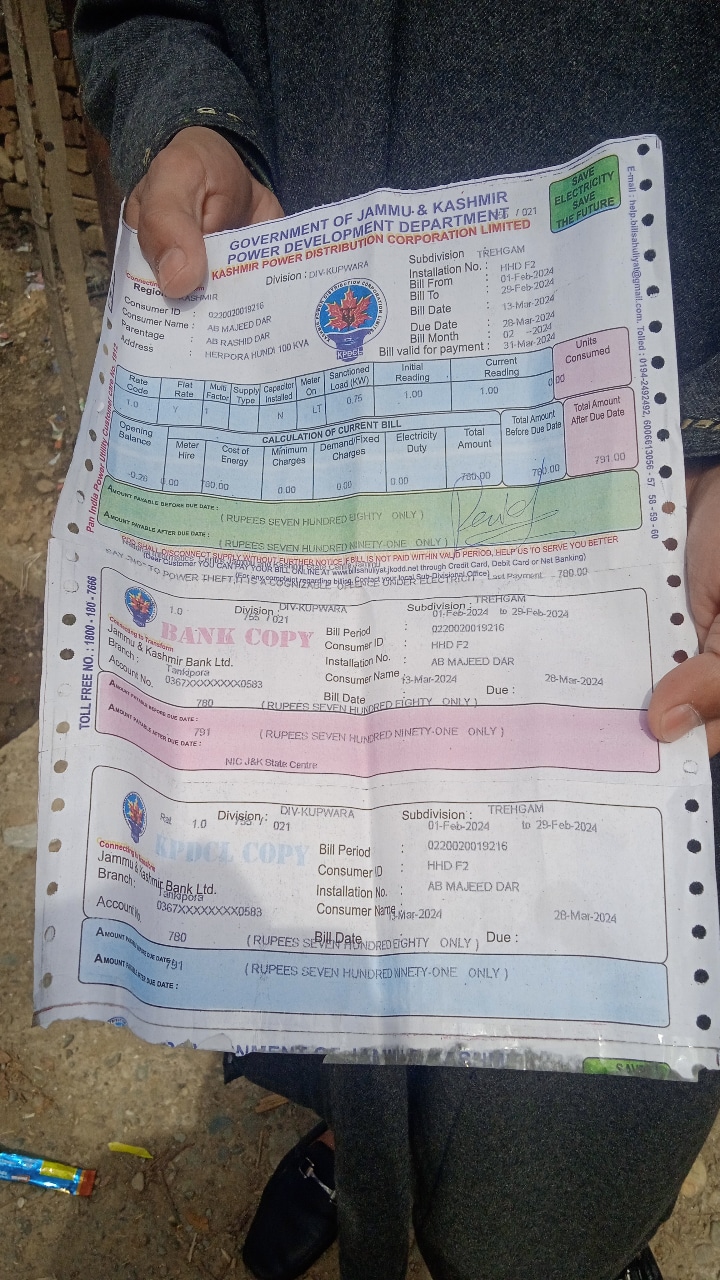

With dreams of furthering his education, Wajid faces a grim reality. “I am very interested in studies,” he says, “but we are a poor family, and we cannot afford IT courses. And besides, there is no electricity here.” Despite these hardships, Wajid’s family continues to receive electricity bills amounting to Rs 700 or more every month, even though the power supply is unreliable – often cut for more than nine hours each day.

than 9 hours a day. Photo: Adil Hussein/2024

In one of the villages, a resident shows an electricity bill of Rs 700, despite being without power for over nine hours a day. “We do not have electricity, especially in the winter. Sometimes, it is hardly two or three hours in two days,” one villager says during a casual conversation, echoing a grim reality for most villages in Kashmir in 2024.

The electricity crisis in Kashmir is not just about the technical challenges of fixing power lines or overloading the system during winter. It is also about the unaddressed dangers posed by dangling electric wires, broken poles and faulty transformers. The Power Department’s inability to address these issues has left villagers vulnerable.

Rafiqa Begum (30) tragically lost her cow, which was the primary source of livelihood for her family of five, when an electric wire fell and caused a fatal electric shock. Her daughter, then just three years old, narrowly escaped death when an electric pole collapsed while she was playing outside. “We live in constant fear,” Rafiqa says, reflecting the daily dangers that come with the erratic power supply.

Photo: Adil Hussein/2024

Most families in Hundi, like many others in rural Kashmir, rely on migrant labourers or traders who work outside the region to support their families. These families, often consisting of only two or three members, face electricity bills of Rs 700-800 each month, despite enduring long hours of power cuts.

Kupwara, part of the region covered under the Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana (DDUGJY), a government scheme aimed at improving power supply, faces persistent electricity shortages. While 1133 BPL (below poverty line) households and 129 villages were electrified between 2015 and 2018, the implementation of the scheme has been inadequate.

Villagers continue to report faulty transformers, unsafe wiring and erratic power supply, but their complaints go unheard. “Every five years, we speak to officials about the outdated transformers and the safety hazards posed by hanging wires. But no one takes action,” says Shaukat Ali, a 19-year-old resident.

In 2019, after the abrogation of Article 370, Jammu and Kashmir Power Transmission Corporation Limited (JKPTCL) was replaced by a new power department directly overseen by the central government. Despite this, residents remain frustrated by the lack of accountability.

“The new power development department talks about reducing power thefts and overuse, but the real issue is the neglect of our basic needs,” says MP Ruhulla, who voices the concerns of Kashmiris. “Power is essential for the people of Kashmir, but it should not be a privilege that others can control. These policies, made by outsiders with no empathy for the people here, are unfair.”

Recently, the Jammu and Kashmir administration entered into a 40-year power off-take agreement with Rajasthan, under which power from Kishtwar in Jammu will be supplied to Rajasthan. Yet, locals in Kishtwar have reported daily power outages of six to eight hours. “They send the power elsewhere, but we have no power in our own homes,” a Kishtwar resident shares. The agreement raises questions about the fairness of power distribution when local residents are left in the dark.

Under the “Power for All in Jammu and Kashmir” initiative, the government sought to improve the region’s power infrastructure. However, despite promises of electrification and the installation of new substations, the situation remains dire.

The National Hydroelectric Power Corporation (NHPC) operates several power stations in the region, including the Kishanganga Power Station. While the government has touted the potential of these plants to meet both local and national energy needs, the reality for people in Kashmir is starkly different. In fact, power outages persist even in the midst of these large-scale projects.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, while inaugurating the Kishanganga Power Project in 2019, claimed that Kashmir has the potential not only to meet its own energy needs but also to generate power for the rest of the country. Yet, as power shortages continue, the reality on the ground suggests a disconnection between promises and delivery.

One of the main reasons for this power shortage is the dependence on hydropower. In winter, as the lakes and rivers freeze, the supply of water to hydropower stations becomes limited, disrupting the electricity supply. Kashmir’s reliance on a single source of energy has proven to be a vulnerability that the government has yet to address adequately.

Meanwhile, people in Hundi and other villages like it continue to struggle with unreliable power, facing bills for electricity they do not receive. As the winter months deepen, many families must contend with freezing temperatures, inadequate heating and the constant threat of electrical accidents.

The impact of these power shortages is especially hard on students and young professionals who rely on electricity for their education and work. A small survey of college students found that 44% reported power outages lasting more than nine hours per day, while 33% experienced outages between six and nine hours daily. These disruptions have led to missed online exams, incomplete courses, and a general sense of hopelessness among the youth.

In the face of rising unemployment, many young people are leaving Kashmir to pursue education and employment opportunities elsewhere. One student shared that the frequent power outages were the primary reason they moved out of Kashmir for higher studies. Others have had to abandon online courses or miss crucial examinations due to power failures.

The lack of social and digital spaces, combined with high unemployment, leaves many young people feeling trapped. Kashmir’s youth, like Wajid, are left to navigate a broken system that denies them access to basic services such as reliable electricity, further compounding the challenges they face in an already conflict-ridden region.

This lopsided development, where the state machinery ignores the needs of its citizens, is a stark reminder of how those in power fail to prioritize the most basic human rights. As Wajid and countless others in Kashmir dream of a better future, the price of electricity has become the cost of their lives —unreliable, unaffordable and often non-existent.