Religious Violence Tests India-Bangladesh Relations: India's Moral Position on Minority Rights Under Scrutiny

Arijit Gupta, TwoCircles.net

New Delhi: Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) MP Manoj Kumar Jha said in the Rajya Sabha (Upper House of Parliament) on December 17, during the Winter Session of Parliament, “We could have asked Bangladesh and Pakistan to learn from us, had our own report on minority rights been good. But that is not the case."

He was critical of India’s ability to position itself as a moral authority on the global stage when it comes to the treatment of minorities. His remarks have struck a chord with critics who argue that India’s domestic record on religious violence and treatment of minorities complicates its moral authority to intervene in the affairs of its neighbours.

Jha’s comments came at a time when tensions between India and Bangladesh are reaching new heights. The recent arrest of ISKCON priest Chinmoy Krishna Das in Bangladesh, his subsequent imprisonment and the violent fallout have ignited widespread protests. At the heart of these protests is the plight of religious minorities in the neighbouring nation, particularly Hindus, who have long faced discrimination and violence from radical elements.

[caption id="attachment_450985" align="aligncenter" width="1169"] Hindu priest Chinmoy Das was arrested on November 25 by the Dhaka Metropolitan Police. He continues to remain behind bars. (Image courtesy/@iindrojit)[/caption]

Hindu priest Chinmoy Das was arrested on November 25 by the Dhaka Metropolitan Police. He continues to remain behind bars. (Image courtesy/@iindrojit)[/caption]

Das, who is a prominent spokesperson for the Bangladesh Sammilita Sanatani Jagran Jote, was detained on November 25 for allegedly disrespecting the national flag of Bangladesh. His arrest sparked massive protests in Bangladesh, where Hindus and other minorities have been calling for greater protection. The monk, known for his activism on behalf of the Hindu community in Bangladesh, was arrested at Dhaka’s Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport as he was preparing to travel to Chattogram.

The arrest has drawn sharp condemnation from India. The Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) expressed deep concern over the treatment of minorities in Bangladesh and urged the Bangladeshi government to ensure the safety of all its citizens, particularly Hindus, and uphold their right to peacefully protest. Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri’s meetings with his Bangladeshi counterparts in December underscored India’s growing anxiety over the situation, with Misri emphasising the need for a "democratic, peaceful, stable and inclusive" Bangladesh.

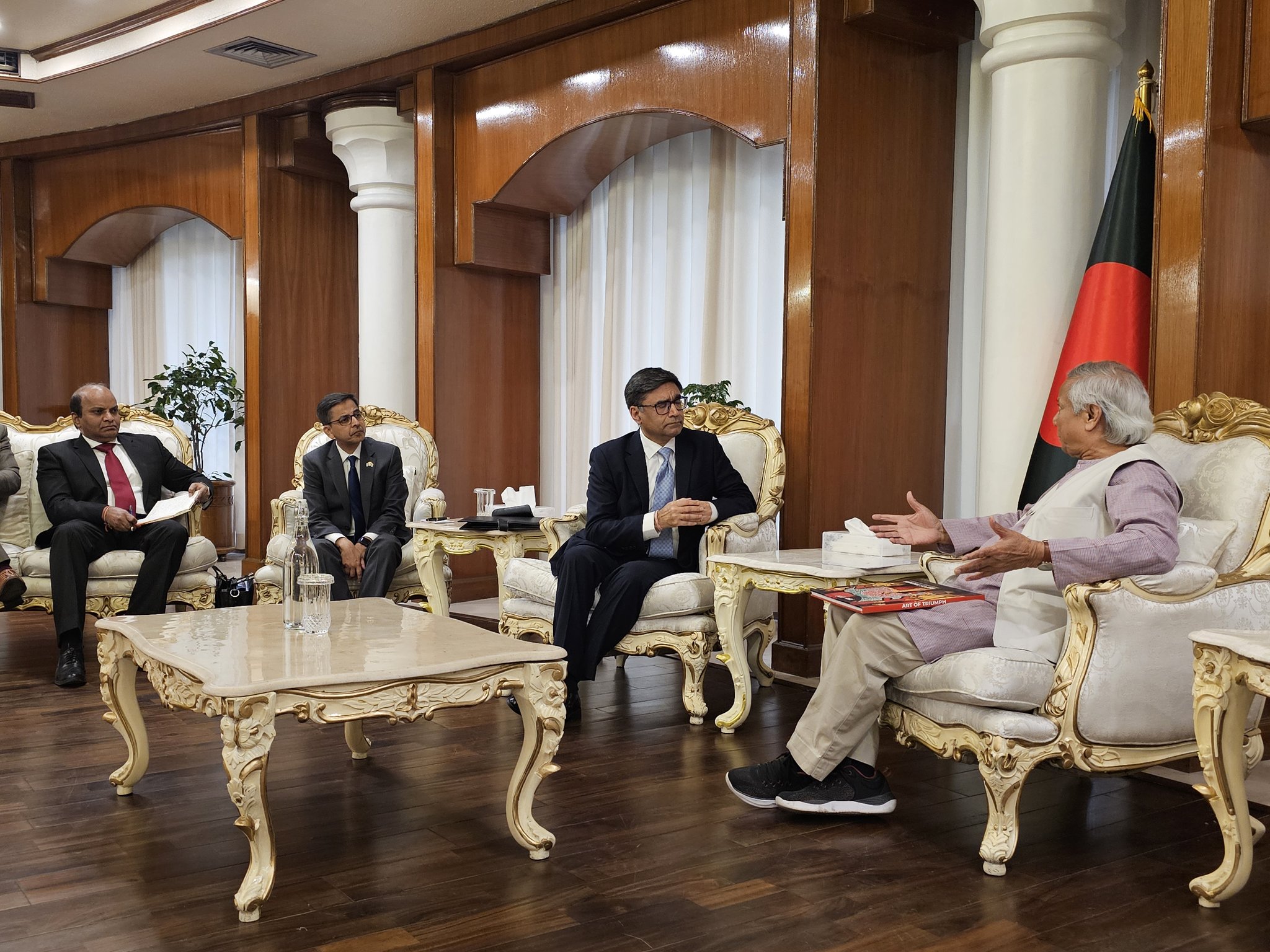

[caption id="attachment_450984" align="aligncenter" width="2048"] (Indian Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri met Bangladesh’s Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus on December 9 (Image courtesy/@sidhant)[/caption]

(Indian Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri met Bangladesh’s Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus on December 9 (Image courtesy/@sidhant)[/caption]

However, Suhasini Haidar, the diplomatic editor at The Hindu, noted that India’s stance on minority rights abroad is complicated by its own internal challenges. "India does not appreciate interference in its internal affairs when people ask about the conditions of minorities, like the Muslims and Sikhs, in India," she pointed out. “But India has clearly made it a major issue with even Prime Minister Narendra Modi mentioning it to US President Joe Biden in September.”

Bangladesh, for its part, has defended its actions. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Dhaka issued a statement on November 26, rejecting India’s intervention in the matter of Das’s arrest. The statement suggested that India’s position misrepresented the facts and undermined the spirit of friendship between the two nations. “Sri Chinmoy Krishna Das has been arrested on specific charges, and his actions do not relate to his advocacy for the rights of Hindus,” the statement read.

[caption id="attachment_450983" align="aligncenter" width="1464"] Indian Foreign Secretary meet his Bangladeshi counterpart Md. Jashim Uddin in Dhaka on December 9 (Image courtesy/@sidhant)[/caption]

Indian Foreign Secretary meet his Bangladeshi counterpart Md. Jashim Uddin in Dhaka on December 9 (Image courtesy/@sidhant)[/caption]

In India, protests against Bangladesh’s handling of the situation have spilled over into several states. Right-wing organisations in Assam, Tripura and Agartala held rallies condemning the attacks on Hindus in Bangladesh and the arrest of Chinmoy Das. On December 2, a protest in Agartala led to clashes with security forces and the breaching of barricades at the Bangladesh Assistant High Commission. The violence prompted the Bangladesh government to summon India’s envoy in Dhaka for a diplomatic discussion.

The unrest continued with protests in Kolkata, where members of the Bengali Hindu Suraksha Samiti burned Dhakai Jamdani sarees and called for a boycott of Bangladeshi products. The protests reflect growing frustration in India over the treatment of Hindus in Bangladesh, as well as frustration over the apparent inaction by Dhaka.

India’s position is further complicated by the broader geopolitical context. The political landscape in Bangladesh has shifted dramatically since the ouster of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in August 2024, following widespread student protests. The new interim government, led by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus, is struggling with internal unrest and rising anti-India sentiment, much of it fueled by Opposition parties like the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh.

According to Aliva Mishra, an assistant professor at Delhi's Jamia Millia Islamia, India has lost a valuable ally in Sheikh Hasina’s government. “The friendly regime promoted people-to-people connections, facilitating trade, tourism and the education sector,” she said. However, she acknowledged that anti-India rhetoric from the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami could pose a significant diplomatic challenge for New Delhi in the future.

[caption id="attachment_450981" align="aligncenter" width="1280"] Indian Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri met Bangladesh’s Foreign Adviser Md. Touhid Hossain in Dhaka on December 9 (Image courtesy/@sidhant)[/caption]

Indian Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri met Bangladesh’s Foreign Adviser Md. Touhid Hossain in Dhaka on December 9 (Image courtesy/@sidhant)[/caption]

Bangladesh’s current interim government, which came to power after the army-backed ousting of Hasina’s administration, is facing increasing pressure both domestically and from abroad. Journalist Sheikh Surfuddin Reza Ali Chowdhury from Bangladesh argued that India’s foreign policy was largely responsible for the current tensions. “Anti-India sentiments have been rising, and this has been compounded by the lack of free and fair media in Bangladesh,” he said. Bangladeshis, according to him, are increasingly dissatisfied with the interim government and its handling of the political crisis.

Despite these challenges, India continues to call for stable and constructive ties with Bangladesh. In a meeting with Bangladesh’s Foreign Secretary Riaz Hamidullah on December 3, Indian envoy to Bangladesh, Pranay Verma, reiterated India’s commitment to maintaining strong bilateral relations. “No single issue should stand as a barrier for bilateral ties,” he emphasised.

India’s stance on the Bangladesh crisis remains cautious. While it has expressed concerns over the treatment of minorities in Bangladesh, New Delhi must also confront its own domestic issues with religious violence and minority rights. As India continues to advocate for the rights of minorities in Bangladesh, it will be expected to demonstrate a more consistent and transparent approach to addressing these issues at home.

This situation underscores the delicate balance India must strike between moral advocacy abroad and addressing the pressing challenges of religious violence and minority rights at home. With both countries facing internal struggles, the future of India-Bangladesh relations hinges not only on diplomatic exchanges but also on how each nation addresses its treatment of minorities.