Why Are Tribals Opposing the Ken-Betwa Link Project? What Are Their Demands?

Satish Bhartiya, TwoCircles.net

Bhopal: Ken-Betwa Link Project has been touted as a solution to water scarcity in the Bundelkhand region. Prime Minister Narendra Modi laid the foundation stone for this ambitious river-linking initiative on December 25. It was seen as a new era of water security. However, behind the government’s vision of progress, a quieter, more painful story is unfolding — the plight of tribal communities whose ancestral lands are being swept away in the name of development. As the foundations for the project were laid, the hopes and fears of the tribals living in the affected areas took a back seat. It raised questions related to justice, rights and the true cost of development.

While the project promises to bring water, irrigation and electricity to millions, it has also brought a wave of protests from the tribals who will lose their land, homes and livelihoods. Their demands for fair compensation, rehabilitation and justice have been largely ignored by the authorities. These protests are not merely a fight for land, but a deeper struggle for their rights, dignity and survival.

What is the Ken-Betwa Link Project?

The project is a large-scale river-linking endeavor designed to transfer water from the Ken River to the Betwa River. It aims to provide water security to the Bundelkhand region. Approved in 2021 by the Modi government, the project has a hefty price tag of Rs 44,605 crores, with Rs 39,317 crores in central assistance. The project is set to bring about significant changes — a 77-meter-high dam on the Ken River, a 221 km canal and the creation of a vast reservoir in Dahodhan, displacing thousands.

This reservoir will allegedly submerge nearly 9,000 hectares of land, including crucial sections of the Panna Tiger Reserve. It is also likely to affect 1,913 families across 10 villages. As the land disappears beneath the waters, so too does the livelihood of the tribal people who depend on it. A report by the Central Empowered Committee in 2019 estimated that 23 lakh trees would be felled for the project. It raised serious concerns about the environmental cost of the initiative.

Tribals Speak Out

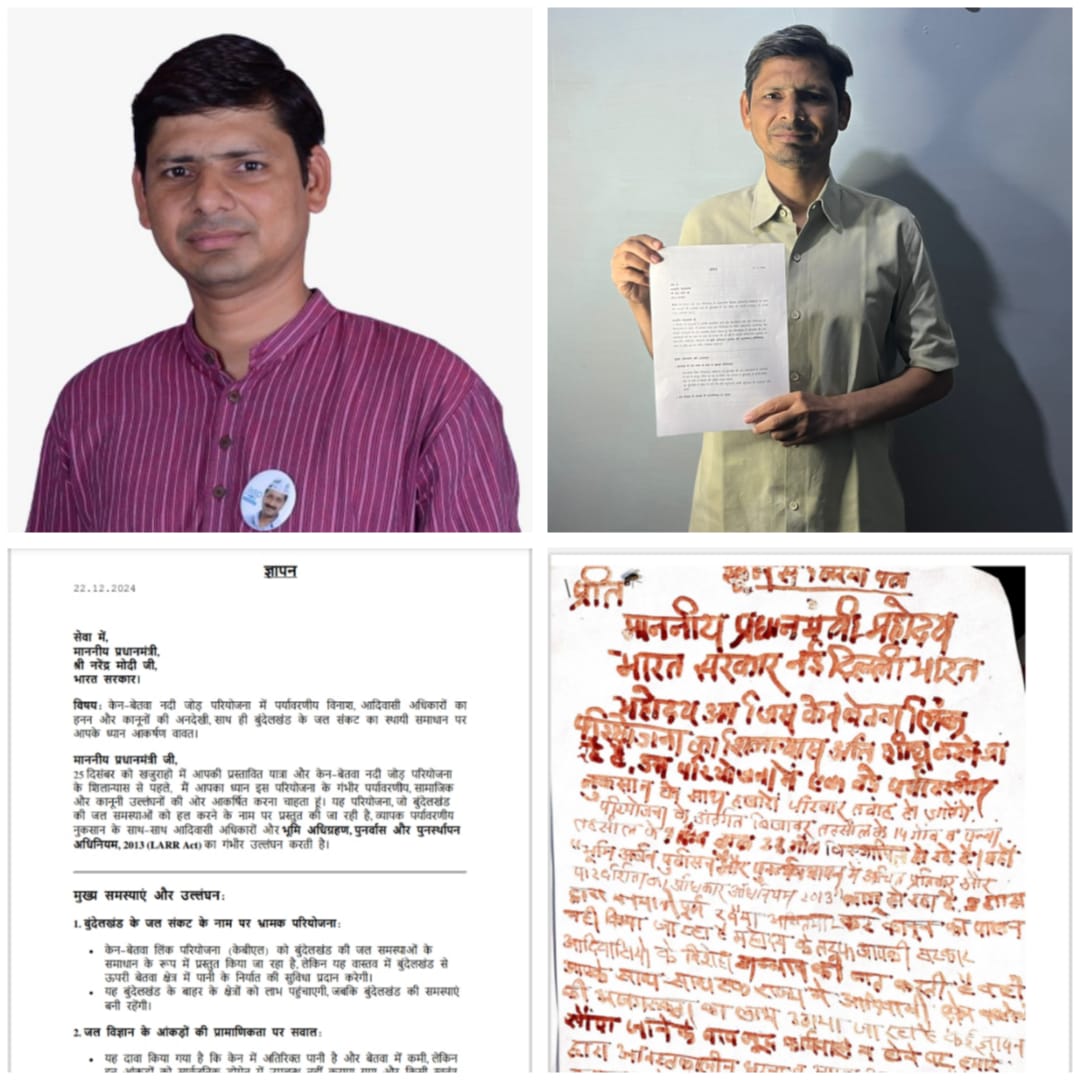

While the government has moved forward with the project, the tribals, who are likely to bear the brunt of its consequences, have raised their voices in protest. Their letters and memorandums to officials and the prime minister reflect a deep sense of injustice and a desperate demand for compensation and rehabilitation.

Mukesh Gond, a tribal leader from the affected villages, describes the pain felt by his community, “The foundation stone of the project may have been laid by Prime Minister Modi, but on that day, people from 8 tribal villages did not light their stoves. No food was cooked in their homes. We, the tribal people, mourned the inauguration as a symbol of our sorrow.”

He continues, “Tribal communities have not received full compensation, rehabilitation, and other facilities. Yet, the project has been inaugurated. What kind of policy is this? What justice is being served? If this project is truly for the welfare of the people, then the affected individuals should first be given their due rights before moving forward. Otherwise, the project will bring devastation to them.”

The villagers of Panna, who face displacement, share their fears. Sumer Singh Gond, from Bilheta village, says, “We will lose our fields, trees, and land due to this project. If proper compensation, employment, and facilities are not provided during the rehabilitation process, the tribal community will never be able to establish itself. Without economic justice, we will never be able to rebuild our lives.”

Munna Lal Gond, another affected tribal individual, voices his frustration, “Before laying the foundation stone, Prime Minister Modi should have understood the pain of the tribal people. We have protested many times, but our demands have not been heard. Our homes, land, and resources are being sacrificed, and the wound of this sacrifice will remain with us forever.”

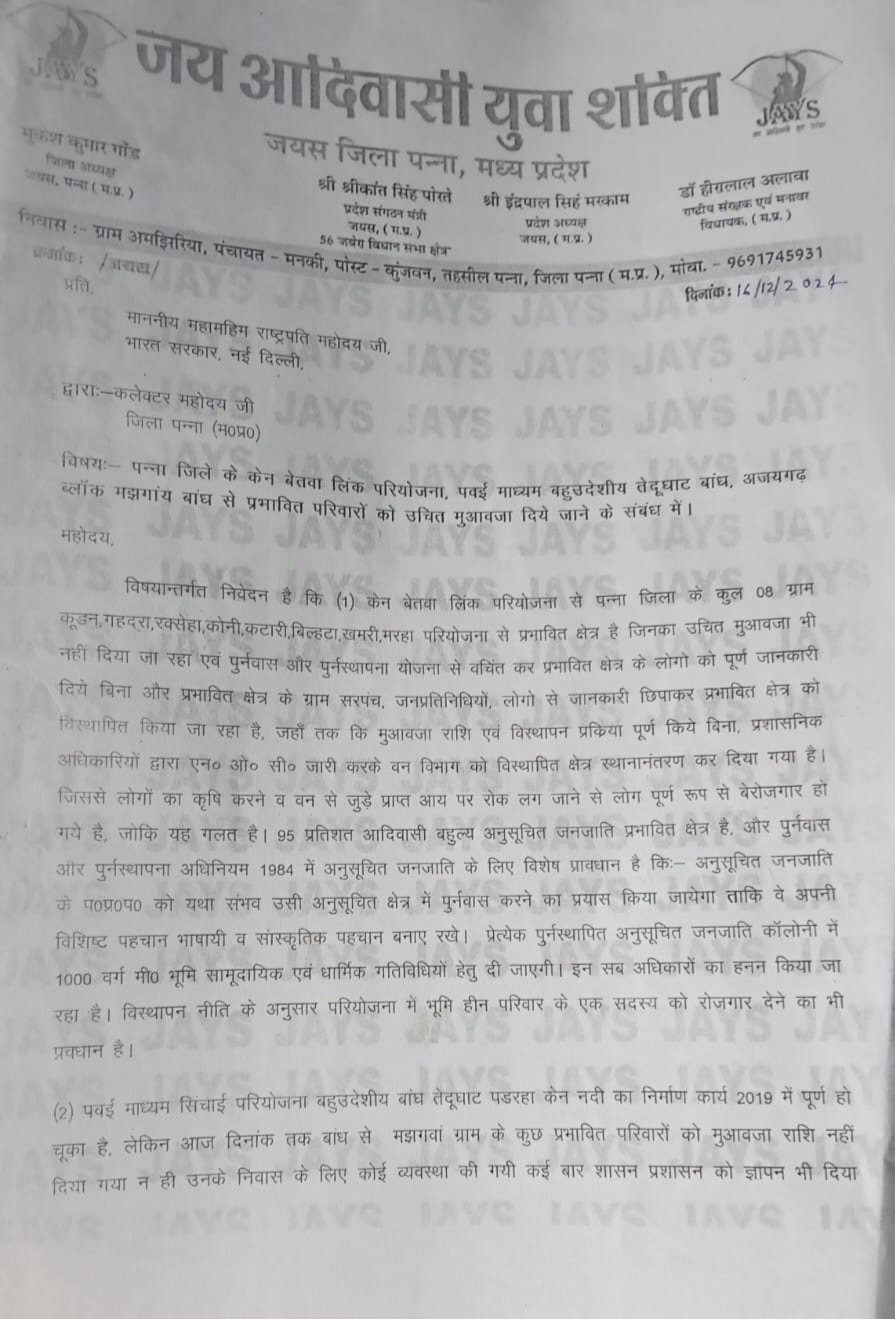

These voices are part of a growing chorus calling for fair treatment. In December 2024, the Adivasi Yuva Shakti Sangathan sent a memorandum to the President Dropadi Murmu, highlighting the plight of the 8 villages in Panna district that are directly impacted by the project. The letter emphasises that adequate compensation and rehabilitation plans have not been provided and that the displacement process has been carried out without proper consultation or transparency.

Environmental and Legal Concerns

Beyond the tribal protests, the Ken-Betwa Link Project also faces significant opposition from environmentalists and legal experts. The project’s implications for biodiversity and the environment are profound, especially in an area like Panna, home to the endangered tiger population and diverse wildlife. Expressing concerns, Subhash C. Pandey, an environmentalist, says, “The natural structure of rivers should be preserved. Linking two rivers could threaten the existence of aquatic life, plants, and animals. Interfering with the tiger reserve and shifting tigers from their natural habitat could cause aggression and distress among them.”

Anil Gautam, head of Environmental Quality Monitoring at the People’s Science Institute, questions the project’s basic premise. “The Ken River has unused water, while the Betwa is over-utilised. Therefore, claiming that the Ken has more water is completely false.” This, along with the environmental destruction caused by the project, raises significant doubts about its long-term sustainability.

Advocate Rahul Srivastava also warns, “The Ken-Betwa Link Project must consider human rights, wildlife conservation, and environmental protection. The project poses significant risks to biodiversity, with the potential loss of both known and unknown species.”

The Struggle for ‘Justice’

The Ken-Betwa Link Project stands as a symbol of India’s ambitious plans for water security and infrastructure development. But for the tribals whose lands are being submerged, it is a stark reminder of the cost of progress. Their fight is not just against the loss of their homes but against a system that they feel has ignored their rights for far too long.

As these tribal communities continue to voice their demands — adequate compensation, proper rehabilitation, and respect for their rights — one question looms large: Will their voices be heard before the waters rise, or will the cost of development drown the hopes of these vulnerable communities?

(Satish Bhartiya is an independent journalist)