Muslim-Yadav Alliance: Engine of Bihar Politics or a Fading Force?

Md Naiyar Azam, TwoCircles.net

Siwan (Bihar): As Bihar heads toward the 2025 Assembly elections, a question looms large: can the once-invincible Muslim-Yadav (M-Y) alliance still swing the state’s fate, or is it losing steam in a changing political climate?

Once the bedrock of Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD)’s power, the M-Y equation now now seemingly faces cracks - both from within and outside. While Muslims still largely back the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), a growing number of young Yadav voters are shifting towards the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), threatening to upend one of the most enduring caste-community alliances in Indian politics.

“The Muslim-Yadav alliance still matters, but young Yadavs are now drifting to the BJP. That is why the BJP is electing more Yadav MPs and MLAs, while Muslims stick with the RJD,” says Bihar Congress Working President Kaukab Qadri.

The alliance was born in the shadow of the 1989 Bhagalpur riots. Muslims turned away from the Congress, seeking political refuge. Lalu Prasad Yadav, leading the Janata Dal at that time, stepped in as that voice. In 1990, he became chief minister and cemented a new political formula - Muslims plus Yadavs - that reshaped Bihar’s electoral arithmetic.

It made perfect sense demographically. Muslims make up nearly 17.7% of Bihar’s population. Yadavs contribute another 14%. Together, they command a decisive 32% vote share, influencing 50 out of 243 assembly seats. In 47 constituencies, Muslims alone form over 50% of the electorate.

The RJD built its base on this powerful axis. Lalu gave them voice. The Mandal Commission gave them policy. The narrative was clear - empowerment for the backward and protection for the marginalised.

“For us, the Muslim-Yadav alliance is like the engine of a train. Others are just passengers. We follow the ideas of JP, Lohia and Lalu - leaders from different castes, but all part of our ideology,” says RJD spokesperson Shakti Singh Yadav.

The glue, however, is weakening. With Nitish Kumar tying and untying knots with the BJP, and the NDA now courting both Yadavs and Pasmanda Muslims, old loyalties are being tested.

“There is no Muslim-Yadav equation anymore. The RJD uses fear to get Muslim votes, but real power stays in one family - Lalu, Rabri and Tejashwi. Muslims are more in number but get fewer tickets,” alleged BJP national spokesperson Shahnawaz Hussain.

The data backs that claim. In 2015, the RJD gave tickets to 48 Yadavs and only 16 Muslims. In 2020, it fielded 58 Yadavs but just 17 Muslims, of whom eight won. The ruling Janata Dal (United) or JD(U) fielded 11 Muslim candidates that year - none won.

“Half the Yadavs have moved to the saffron party. Muslims still vote for secular parties, but it is not enough. If Muslims are 18% and Yadavs 14%, then candidate lists should reflect that. But they don’t,” says Akhtarul Iman, MLA from Amour and chief of the Bihar wing of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM).

In the 2020 Bihar Assembly polls, 65-70% of Muslims voted for the Mahagathbandhan (the RJD, the Congress and the Left alliance). The alliance performed well in Muslim-concentrated regions like Seemanchal (northeastern part of Bihar).

However, the AIMIM made a dent - securing five seats in Seemanchal and drawing 15-20% of the Muslim vote. The rest, about 10-15%, scattered across smaller parties and independents. The share of the ruling National Democratic Alliance or NDA (the JD-U, the BJP, the LJP and other smaller parties combine) was minimal, worsened by laws like the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA).

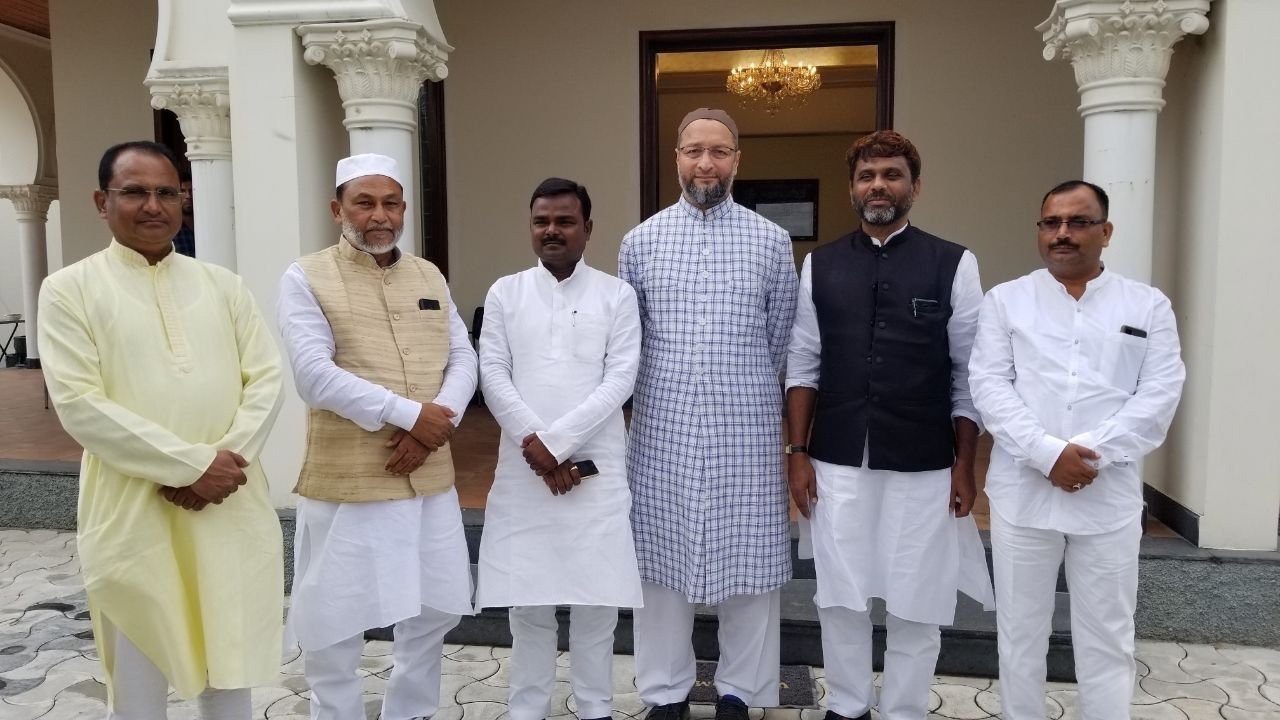

[caption id="attachment_452107" align="aligncenter" width="1280"] Five AIMIM Bihar MLAs with party chief Asaduddin Owaisi in Hyderabad, November 2020)(Courtesy: X/AIMIM)[/caption]

Five AIMIM Bihar MLAs with party chief Asaduddin Owaisi in Hyderabad, November 2020)(Courtesy: X/AIMIM)[/caption]

‘Mission’ or ‘Math’?

The alliance, once fueled by passion, now appears reduced to calculations. “For the older generation, it was a mission. For today’s parties, it is just math,” says Nishant Desai, founder of political consultancy Ink Insight.

Young Yadavs, he says, talk about nationalism, jobs and Modi. Muslims, according to him, are exploring options like the AIMIM. "Both groups have been used politically, but they have also benefited,” he adds.

Veteran journalist Kanhaiya Bhelari echoes that sentiment. “Caste still dominates Bihar politics. That is why the BJP has never formed a government alone. But today, the M-Y alliance works more like a vote bank than a movement,” he says.

He adds, “Young Yadavs are not rallying behind Tejashwi the way they did behind Lalu. But both groups still want representation and protection.”

The JD(U) is trying to flip the script. “The era of vote-bank politics is over. People now vote for development, not just caste. NDA works for all - from A to Z,” claims JD(U) spokesperson Mayank Sinha.

With the 2025 polls approaching, every party - from the RJD to the BJP, the Congress to the AIMIM - is recalibrating its pitch to win over the Muslim-Yadav axis. The alliance may be fractured. But its influence endures.

Whether it serves as the engine or gets left behind as a legacy, the Muslim-Yadav coalition remains central to Bihar’s electoral story.