Devanshi Batra, TwoCircles.net

‘Dekho nigaahein naaz se Delhi ke nazaare, ye tehzeeb ki jannath Jamuna ke kinare,’ recited Mirza Sikander Beg Changezi, quoting the poetry by his father, Naseem Mirza Changezi.

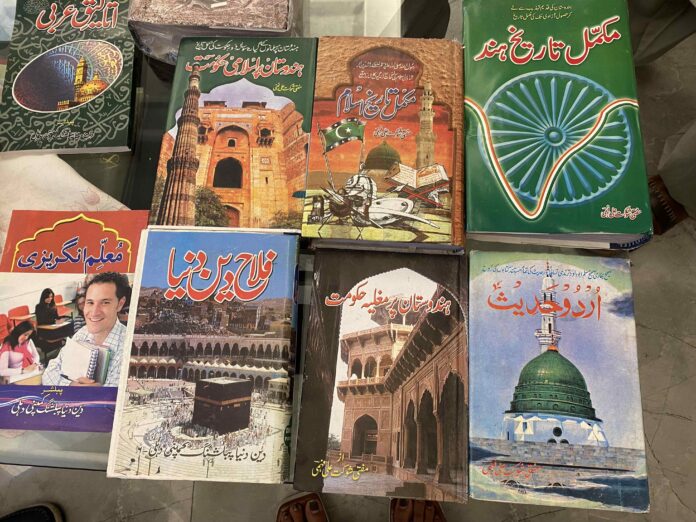

Nestled in the narrow lanes of Old Delhi, the Urdu Bazaar was once the beating heart of the city’s intellectual and cultural life. Established during the Mughal era, this bustling marketplace was more than just a collection of shops; it was a vibrant hub where scholars, poets, and lovers of the Urdu language gathered to share ideas, purchase books and immerse themselves in the rich literary traditions.

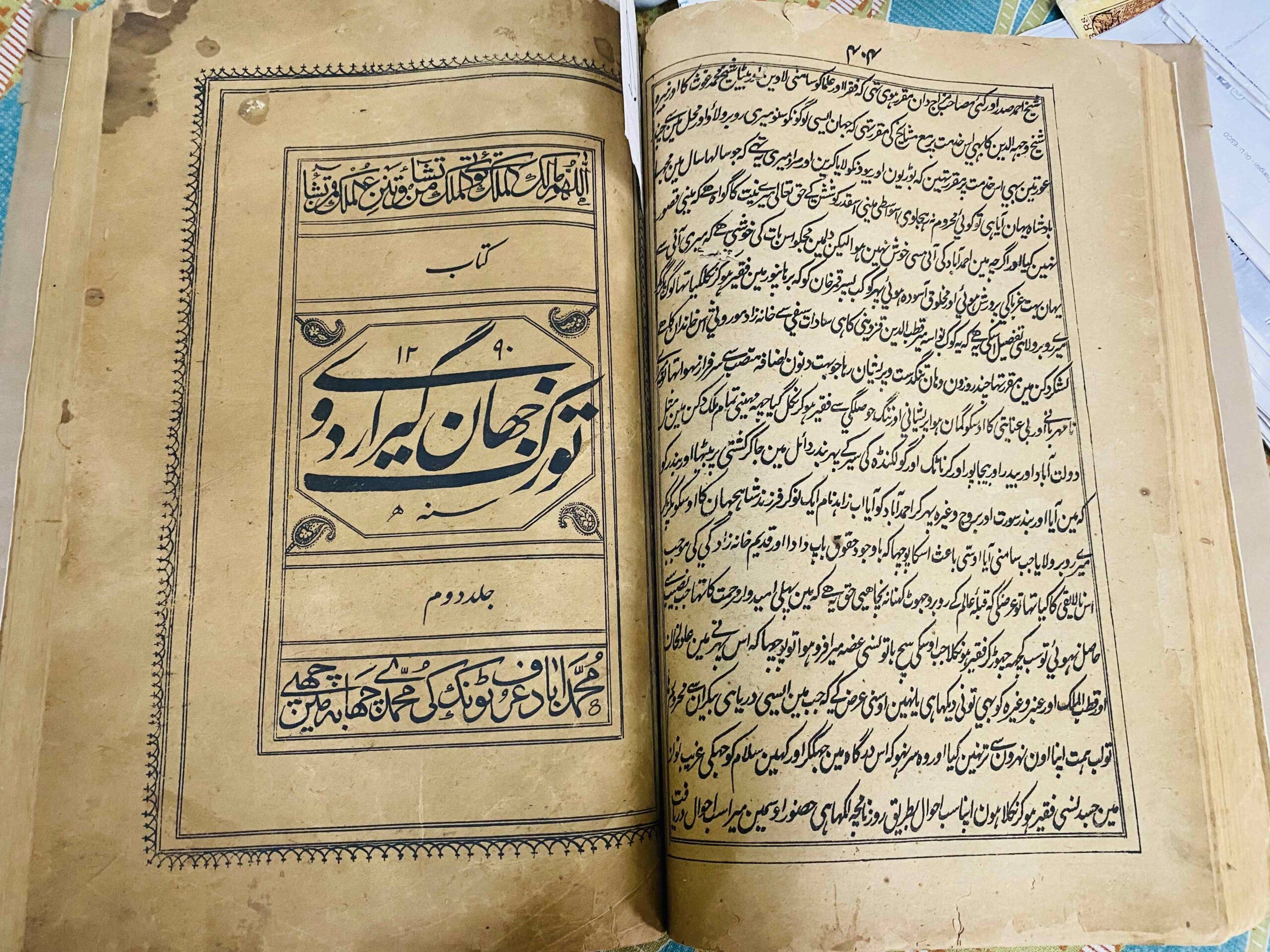

Urdu Bazaar grew in prominence during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly under the British Raj. It became synonymous with the flourishing of Urdu literature and culture, with its shops housing rare manuscripts, poetry collections and educational texts. The market attracted luminaries like Abdul Kalam Azad, who frequented the bazaar for inspiration and joined the Mushairas. It was a place where intellectual discourse thrived, and where the Urdu language was celebrated and preserved.

“This full road near Gate No. 1 of Jama Masjid was full of Urdu bookstores,” reminisces Shahid Ur Rehman, 70, the fourth-generation owner of Kutub Khana Rahimiya, a shop that has been in his family since 1905.

In recent decades, however, the Urdu Bazaar has experienced a steady decline, with only 8-10 shops remaining. The reasons are manifold, from diminishing patronage of Urdu literature to the rise of technology. The growing dominance of Hindi and English in Delhi led to a reduced demand for Urdu publications.

“Urdu Bazaar was a hub of scholars and intellectuals,” reflects Arshad Ali Fehmi, 59, owner of Din Dunia Publishing House, one of the oldest Urdu publishers in the area, whose family has been here since 1921.

The advent of digital media and e-books further eroded the market’s appeal. Where once the bazaar bustled with customers, today, many of the shops have shuttered, replaced by eateries. The few remaining bookshops struggle to survive, their shelves collecting dust as foot traffic dwindles.

“The Urdu Bazaar was once alive with Mushairas held right on the streets, but now it’s just a khana bazaar. The Urdu readership is diminishing; everyone wants to read English now, and digitalization has changed the landscape a lot,” says Rehman.

The partition of India in 1947 saw a large-scale migration of Urdu-speaking Muslims to Pakistan, significantly impacting the market’s customer base. “Urdu Bazaar bore the wrath of Partition; it killed Urdu Bazaar,” recalls Mirza Sikander Beg Changezi, 72, a descendant of the Changezi family whose ancestors witnessed the bazaar’s transformation over the years.

A Language in Peril: The Broader Implications

The decline of the Urdu Bazaar is emblematic of the larger decline of the Urdu language in India. Once the lingua franca of northern India, Urdu now struggles for survival amid the dominance of Hindi and English. The language, which played a crucial role in the cultural and political life of the region, is increasingly marginalized in schools, media, and public life.

“In this constituency, there used to be around 23 schools, 13 of which were Urdu schools. But now, even in those schools, Hindi or English is taught instead of Urdu,” says Fehmi.

“Earlier, booksellers used to sell manuscripts, then slowly moved to books. Urdu Bazaar used to sell one-of-a-kind books. Calligraphers also lost their livelihood. The Urdu Bazaar was a place where all the intellectuals used to sit. But now, this business is not profitable, and that’s why people are leaving it. People are now thinking of opening restaurants here,” adds Changezi.

For many, the decline of Urdu is not just a linguistic issue but also a cultural one. The language is deeply intertwined with the history, art, and identity of a significant section of India’s population. Its diminishing presence is seen by some as a loss of cultural heritage, a fading of the syncretic traditions that once defined the Indian subcontinent.

“Ninety-percent of the Urdu Bazaar is dead. People used to come from faraway places. I used to sell thousands of books; now, I barely sell 20. This place is facing decay; education is being completely finished from here, especially the Urdu language. Why can’t educational walks take place here? Why only food walks?” Fehmi adds, with a note of despair. “After a decade, the Urdu Bazaar will be finished. My son will not continue this magazine; it will die with me.”

The Few Who Remain

Despite the challenges, a handful of shopkeepers and publishers remain steadfast in their dedication to preserving the Urdu language and literature. These individuals, often elderly, have spent decades curating collections of rare books. They see their work as a labor of love, a way to keep the flame of Urdu literature alive in a world that seems increasingly indifferent.

For these custodians, the struggle to keep their shops open is not just a commercial battle but a fight against the erasure of a rich cultural legacy. They even distribute free Urdu books, hoping to ignite a spark of interest in the younger generation.

“This business may no longer be profitable, but I continue because Urdu has raised us. Our love for this language will never die — Urdu is our bread and butter,” says Fehmi.

The story of the Urdu Bazaar is not just about a market or a language; it is about the struggle to preserve identity in the face of change. The Urdu Bazaar, though diminished, still stands as a testament to the rich history of Delhi and the enduring spirit of its people. Its future, however, hangs in the balance, dependent on the actions of those who value what it represents. As the sun sets over the narrow lanes of Old Delhi, the echoes of a once-thriving market linger, a reminder of a heritage that must not be forgotten.

Rehman is still hopeful and says, “But Urdu won’t die — no language dies. Our independence slogan, ‘Inquilab zindabad’, was an Urdu slogan. How can Urdu die?”

All photos by the author