Mirza Mosarraf Hossain, TwoCircles.net

Imperialism is an undeniable reality in the world, with dominant, majority groups historically oppressing weaker, minority communities. However, imperialism is not eternal; it fades when the oppressed gather sufficient strength to resist. History, especially in the mid-20th century, offers numerous examples of colonised nations overcoming their oppressors, with key changes in social, political, cultural and intellectual spheres. The end of European colonialism and the post-World War II shift in the global political economy ignited efforts to rewrite the history of colonised nations, driven largely by social, political and cultural resistance.

Central to this resistance was the cultivation of literature. Intellectuals played a crucial role in shaping societal transformation, crafting ideas for how society should function, which were then implemented by state and societal systems. This role of intellectuals remains vital in independent, democratic countries today.

However, intellectualism is not always an agent of change; those opposing the state may face exile or imprisonment, a fate well exemplified by Antonio Gramsci, whose ideology eventually gained global academic recognition.

In the Bengali Muslim society of West Bengal, we observe a community divided into two distinct groups: a largely uneducated, impoverished farming class and a smaller educated class of semi-educated businesspeople, urban workers and migrant laborers. Despite limited resources, efforts to educate children through community-driven initiatives like Al-Amin and other schools are beginning to yield results.

More people are now earning academic degrees and securing jobs in both public and private sectors, contributing to the rise of a silent middle class. These individuals are becoming increasingly aware of social, political and environmental issues, with a growing number vocalizing their grievances through literary culture, journals and magazines.

Yet, within this educated class, there exists a significant ideological divide. Older generations of intellectuals, prominent within various sectors, appear to have neglected their responsibility to address the unique challenges facing the Bengali Muslim community. Instead, they often align themselves with the narratives of the majority Bengali Hindu community, following the legacy of the 19th-century Bengal Renaissance. This has led to a failure to challenge the social, economic, and cultural dominance of the Hindu majority. Instead of pushing back against this dominance, Bengali Muslim intellectuals seek validation from the majority, inadvertently perpetuating the hegemonic discourse about their own community.

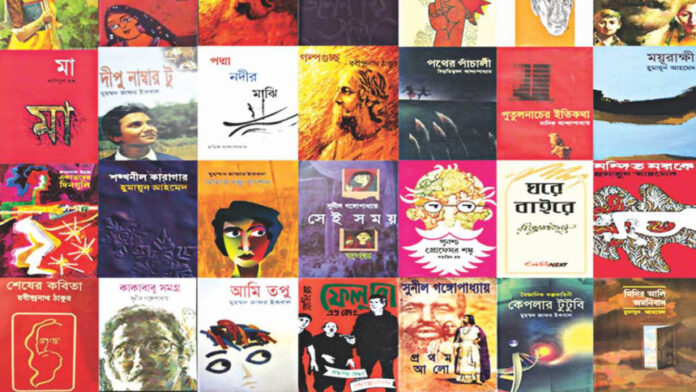

This intellectual duplicity has had severe consequences, particularly in the realm of Bengali literature. Since the Partition of Bengal, much of the literature produced by Bengali Muslim authors has contributed to the negative stereotyping of their community. Literary works that attempt to showcase themes of cultural assimilation or promote Bengali linguistic chauvinism often reinforce harmful perceptions of Bengali Muslims, which were first cultivated during the 19th-century rise of Bengali nationalism. This exclusion of Bengali Muslims, particularly by figures like Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, continues to influence contemporary literature.

Many Bengali Muslim authors, such as Abul Bashar (Phul Bou), Afsar Ahmed (Bibir Talaq), Abdul Jabbar (Ilishmari Char) and newer voices like Sourav Hossain (Chhobed Mistry’s Khutba) and Hamir Uddin Midya (Luiton Bibi Kathi Korle Ja Kichu Hoye), depict Muslim women in derogatory terms, focusing on themes like divorce, polygamy and sexuality. Similarly, more recent works, such as Ismail Darvesh’s ‘Talashnama’, further perpetuate the stereotype of Bengali Muslims as being overly influenced by religious clerics and practices.

On the other hand, the works of non-Muslim writers like Amar Mitra, Sachin Das, Gourkishore Ghosh and Swapanmoy Chakraborty also propagate a one-dimensional, stereotypical portrayal of the Muslim community, making it difficult to distinguish between the two. These literary works, despite their negative portrayal of Bengali Muslims, are often awarded prestigious honors and recognition.

In this context, the words of Sher-e-Bengal A.K. Fazlul Haq, the first prime minister of undivided Bengal, resonate deeply: “When you see the Babus (genteel men) of Kolkata praising me, you will understand that I am working against your interests.”

Faced with such division, what should Bengali Muslim intellectuals do? Should they continue perpetuating the majority narrative, or should they strive to create an alternative discourse?

Another concerning trend is the increasing number of Bengali Muslim intellectuals who distance themselves from their religious identity. Many gain recognition in the majority society, often being invited to TV shows, newspapers, and editorials due to their Muslim background. However, they often conceal their Muslim identity to be more accepted in mainstream society. If this intellectual bankruptcy continues within the emerging educated society, it could have disastrous consequences for the entire community in the future.

In academia, many Bengali Muslim youths, despite overcoming numerous obstacles to pursue higher education, show little interest in studying their own community. This is especially evident in fields like social sciences and literature, where research on their community’s history, culture, and identity is often neglected. Without the opportunity to present their vision for cultural revolution, the new generation may not be able to preserve their cultural practices and identity.

The future of a nation depends on the preservation and study of its cultural and social heritage. This requires examining its traditions, challenges, creativity, intelligence, and relationships with both allies and adversaries. In the case of Bengali Muslims, this process is currently stunted. The intellectual stagnation of Bengali Muslim society, marked by a failure to resist dominant narratives, is often termed intellectual bankruptcy. To counter this, the works of thinkers such as Ali Shariati, Talal Asad, Hamid Dabashi, Salman Sayyid, Saba Mahmood, Layla Abu-Lughod, Asma Barlas and others should be brought into discussion to shed light on the community’s fate. Intellectual inquiry must be expanded beyond narrow limits and confined spaces.

Ultimately, the future of Bengali Muslim intellectualism hinges on the ability to break free from the dominant hegemonic discourse. Only through comparative study and broader knowledge acquisition can intellectuals contribute meaningfully to their community and ensure its survival and growth. If the same dominant narratives continue to be regurgitated under the guise of alternative discourses, there will be no justification for calling them alternatives.

(Mirza Mosarraf Hossain is a Lecturer in Humanities at Medinipur Sadar Government Polytechnic, Midnapore, West Bengal. He can be contacted at [email protected]. The views expressed are personal.)