Book Review: People having no record of Patriotism make Muslims ‘Perpetual Others and Losers'

By Afshan Khan for TwoCircles.net

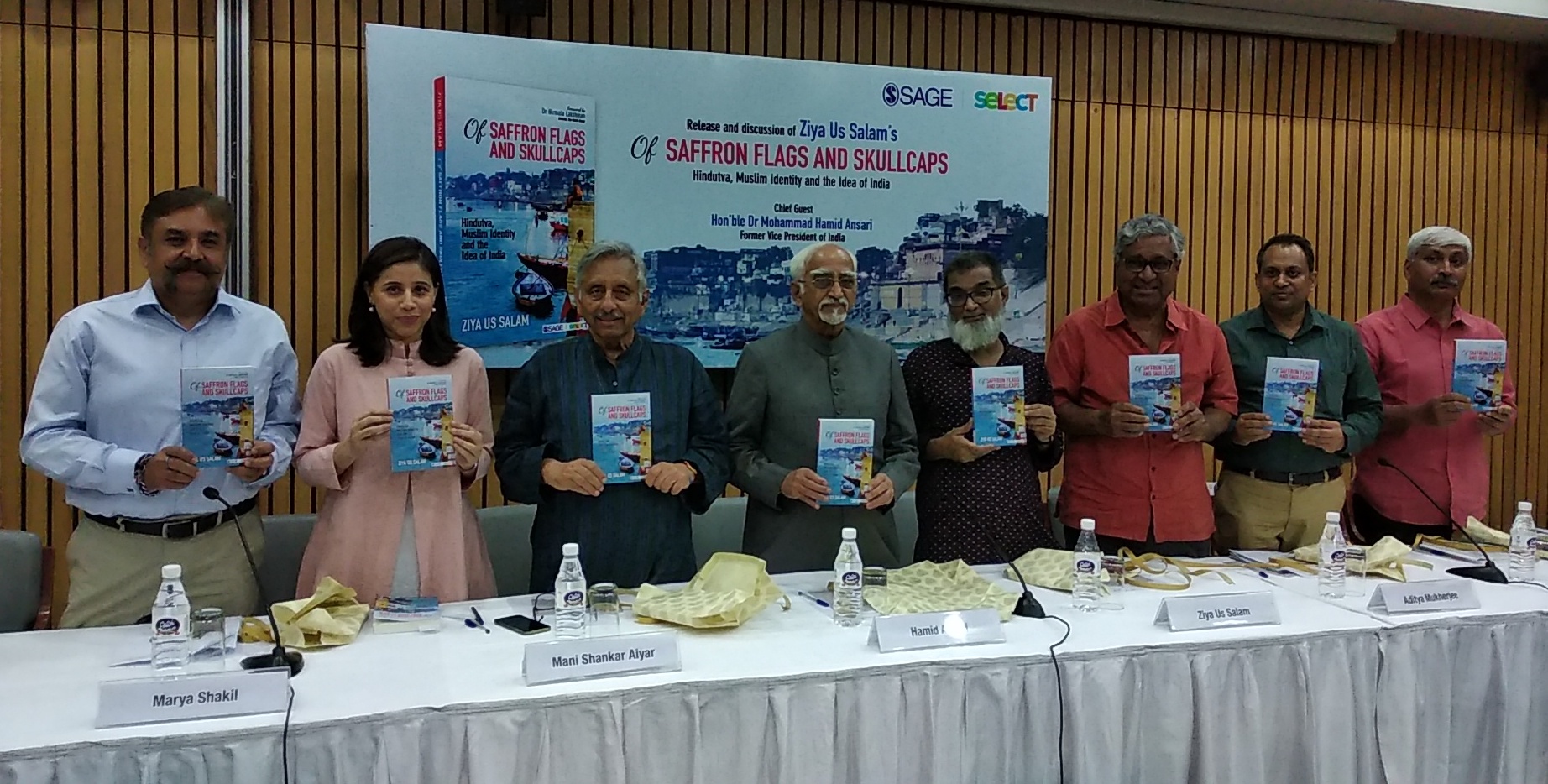

Book title: Of Saffron Flags and Skullcaps: Hindutva, Muslim Identity and the Idea of India Author: Ziya Us Salam Publisher: Sage Pages: 295 Price: 495

Fed up with the biased anchors, disqualified clerics, Hindu Muslim remarks of politicians, RSS’ agenda, mob lynchings, distortions of history and much more? Use this anguish and utilise your energy for the newly-launched book of Zia Us Salam, ‘Of Saffron Flags and Skull Caps: Hindutva, Muslim Identity and The Idea of India’.

The book ridicules everyone from the so-called heroes of Hindutva to the forerunners of the same. Salam comments that RSS Pracharaks are poor students of history, in fact, they hardly attended any history classes. In answer to their allegations against Muslims, he shows us through the writings of historians like Romila Thapar, Bipin Chandra, Irfan Habib, and many others, the untold facts about history. He thanks his lecturers for introducing these historians who provide an alternative account of history than what we're taught in our school time. These historians analysed history in a grey shade, no one was an angel and no one a devil, opposed to the narrative of Hindutva for whom even Akbar has become the 'new age, Aurangzeb'.

It tells how Hindutva has put an obstacle in the Idea of India and how ‘extensively divisive’ Hindutva has created an existential threat to the Muslim identity in India. He shows evidence from history that being a Muslim in India has never remained easy. His anguish against Modi regime is mostly for the reason that for the first time in the History of India a murder accused was wrapped in the national flag on his last journey.

What a brilliant move of starting with Kamlesh Tiwari and ending at Md Allama Iqbal. The clear contrast is understandable. He raises a question regarding Kamlesh, ‘his antipathy towards Muslims seemed understandable but why his hostility towards Mahatma?’ He tries to find out where Tiwari gets his ammunition for sustained hatred? According to Ziya, contemporary voices of Hindutva get an inspiration from Savarkar who paved the way for modern-day extremists.

On Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay who portrayed Muslims as Asuras and enemies in Anandmath, he utilises his anger and says, 'Even after 90 years, I remain the other, the Asura, the demon'.

Ziya criticises the move of RSS and BJP at attempting to appropriate Mahatma Gandhi, Bhagat Singh, Sardar Patel, and Ambedkar. 'A choose and pick policy is applied to fill the gap in their own narratives.', Ziya argues. When they want to put down Nehru, they try to glorify Ambedkar. The author reminds that Ambedkar had drawn a parallel between Savarkar and Jinnah. Here the journalist Ziya reminds the Rohith Vemula case and sharply remarks, had they been a follower of Ambedkar, Rohith would have been alive.

In contrast to RSS’ history of having no record of patriotism, every time accused of not hoisting the national flag, disrespecting it, flattering Britishers, and having protested against the Republic day; author details the history of Jamiat Ulema e Hind which has a record of playing crucial role in the freedom struggle, in uniting Hindus and Muslims. Even today it has evolved with the gradual time period, playing important role in awakening the Muslims and Dalits and taking all together for a common cause. Here the book is distinct from what the other books have done. He courageously talks about Jamiat which other people usually avoid.

The author does not only talk ‘about Muslims’ but talks ‘to Muslims’ which makes the book unconventional. For them, the message is clear. Learn what is the difference between Jihad and Ijtihad. The former is misunderstood and the latter is forgotten altogether. He complains that even Muslims have not been engaged with the two terms intellectually. Ijtihad is about independence and rational thinking. How can one forget Allama Iqbal in any discussion about nationalism or rationalism? So he does remind that Iqbal called Ram, the 'Imam e Hind', this is the fact which was discussed in Neyaz Farooquee's book too. But here the motive is much wider. He tells how Iqbal is taken for granted by Muslims too. He reminds us that his poetry was inspired by Qur'an and the derived part of his poetry from the verses of Qur'an. The author remembers Iqbal as a diehard nationalist who later became an internationalist. His 'Saare Jahan Se Achha' has been disappeared from the public diaspora because, sadly, the new generation see enchanting 'Bharat Mata ki Jai' as the only glorification of India.

He elaborates the ongoing menaces of Hindutva, whereas the world of Islam is going through transformations.

Being a student of Al Hidayah institute, run by the students of Dr Farhat Hashmi, I felt enormous joy to read the author praising her, unlike other Muslims who fear any discussion about Islamic preacher and Qur’an. He is upset with the current status of Madrasas but the arrival of Dr Farhat Hashmi seems like a relief. He comments, "where qualified maulana from places as distinguished as Darul Uloom Deoband or Nadwatul Ulama failed to get the common Indian Muslim to know the meaning of Qur'an, a foreign woman succeeded. What's more, she spurred many of her ilk." (P.215)

Now women who kept themselves busy within the four walls of the home have started attending these classes where they are taught the uses of new technology and the meaning of Quran word by word, with an explanation. The story of Ikhlasi Begum is not less inspiring. She, for the first time, gets to know that she can offer namaz in the mosque and this is her Right safeguarded by the Quran.

He sharply criticises those who spread lie and fear by presenting facts and arguments through a huge literature that is referred to in the book. After explaining the alienation story of Muslims, he tells us about the story of ‘not being the other’. And here the reader needs to pay attention. He is dealing with those individuals who have a Muslim name but they defame Islam. He starts with Noor Zaheer’s book, ‘Denied by Allah’. He enlightens her and provides counter arguments by citing the verses of Qur'an directly which she had not even bothered to read roughly.

How can we expect him to keep silent on Tarek Fatah? He tells, with his 'quote on demand' ways, Tarek has become a regular face on Indian television. He is someone who runs away from discussions and dialogue, illogical, and therefore he is not the 'Other'.

In contrast to this man, the author discusses Maulana Wahiduddin, a soft-spoken man who always prefers dialogue and discussion. He is someone who has always put emphasis on jihad, meaning, not an aggressive war.

Interestingly, the author questions himself, whose book should he keep on his shelf? He says, both. One for understanding how anger clouds judgement and another for staying calm and talking about peace. (P.229)

No author can afford to ignore the ‘terrorism’ angle that Muslim identity has been stigmatised with. Ziya urges to realise that these young minds despite facing the cruellest form of discrimination, do not lose hope in judiciary and Constitution. The community has received deep hurts but still manages to spread peace, and now it's the high time to realise that they are an integral part of this democracy.

Unlike the other writers, he does not leave us with a depressing ending, rather he offers optimism. He reminds that India still has the potential to go on the right track it had been visioned for. Remember how the tricolour wristband unites all the Muslim pilgrims during Haj, he reminds.

He emphasises to engage with each other's culture and religion. 'a thousand years ago, we had Al Beruni who studied Vedanta like none else. Then we had flowering inter-religion dialogue during the Mughals…’, he adds.

The author is optimistic regarding the efforts of people who started and joined campaigns like, 'not in my name' and the returning of Akademi award by Sahgal as they give a message that taking a stand for a Dalit, Muslim and Christian is no more suicidal. 'inclusive India has always won against the forces of exclusion', he reminds.

People who are looking to see a caste angle in the book may feel a little disappointed. He does talk about the issues of Dalits and conversion angle but does not go deep into the discussion of how caste has played a role in making the idea of India. The language of the book is very easy to understand and the book has a lot to argue which has been missing in other books and therefore it demands the attention of the readers.