Sidra Fatima, TwoCircles.net

“Haye kasher zev, me che cheeni drieh, cze myeen khabar, cze myeev nzar, cze myeen shaoor’ich sonzil zich, cze myeeni zameer’ich mecx’sang.”

(O Kashmiri language! I swear by you, you are my awareness, my vision too, the radiant ray of my perception, the whirling violin of my conscience.) — ‘Hymn to Language’, Rehman Rahi

Kashmir — where conflict and political upheaval always dominate headlines — is witnessing a quieter but equally pressing struggle, wages by a young girl, against the fading of the Kashmiri language, Koshur.

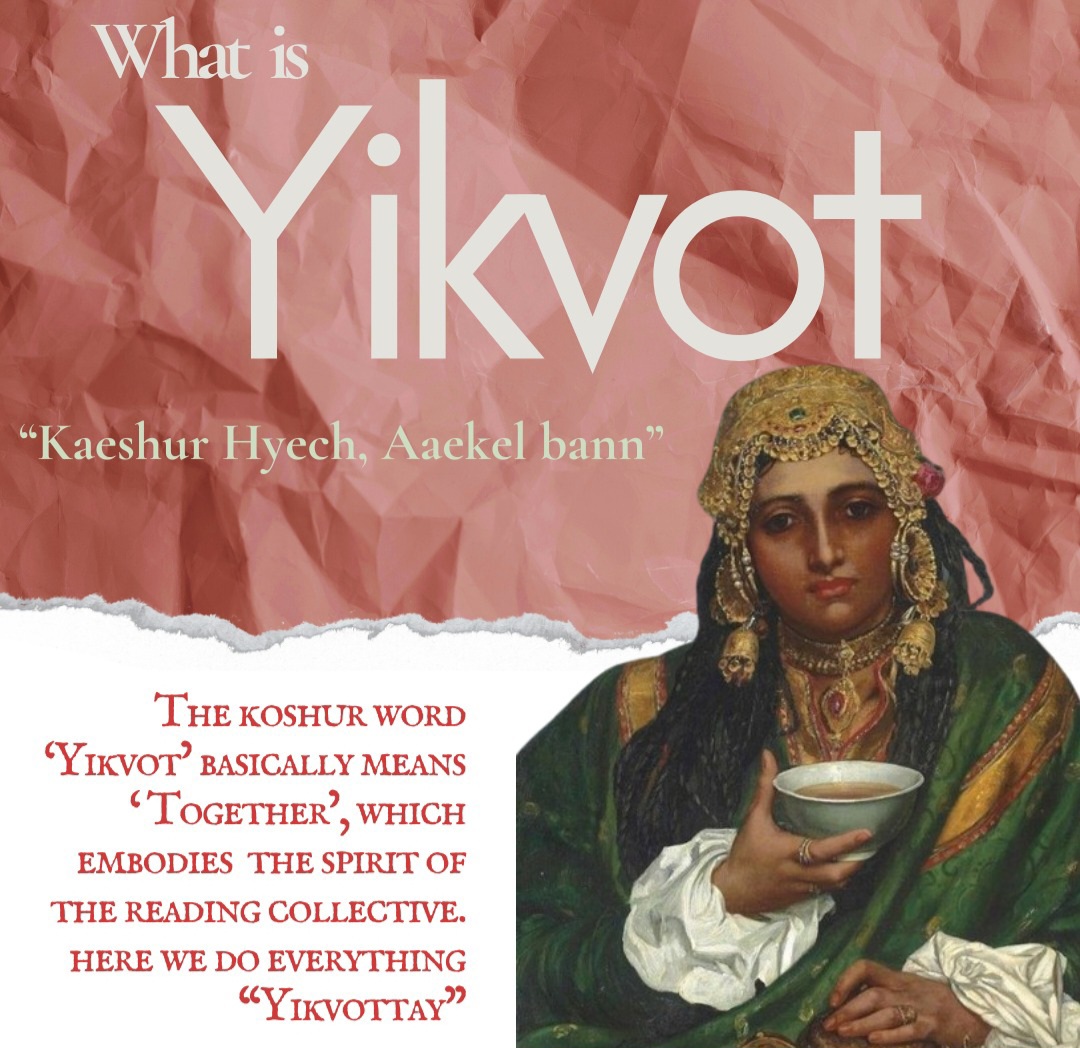

Seerat Hafiz, 22, a writer and peacemaker, has founded Yikvot — a reading club that means “together”. Her mission is to preserve and revive the beauty, rhythm and soul of Koshur, especially among the youth.

“For me, this language, which is now endangered, has been the voice of my grandparents. With English and Urdu-speaking parents, we often reserved our last bit of Kashmiri for the elderly, trying to converse only to bite back our tongue. This stands as a testament of resilience and faith,” she says.

She adds, “Kashmiri has a beautiful ring to it. I often say that it is impossible to translate any language without it missing its essence, its love and its sweetness. Kashmiri is one such language that not only is soulful and sweet but all kinds of emotions get expressed in it. I believe what was interesting to our readers was the quirky touch of Kashmiri added to the translation of the world-famous Russian author Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment.”

What began as a scribbled idea on a coffee shop napkin in 2024 has since blossomed into a vibrant literary movement, now boasting over 300 students. Through weekly meetups, social media outreach and intergenerational storytelling sessions, Seerat is not just preserving Koshur — she is giving it new life.

A revival

“The most exciting aspect of attending this class is the chance to get deeply involved with Kashmiri literature. The guest lectures, most of all, have been wonderfully insightful, making us get more intimately attached to our mother tongue. It was through Yikvot that I actually realised the richness of my own emotional attachment to the Kashmiri language,” says Fabiha (18), a student at Yikvot.

“Finding Yikvot marked a turning point for me. It made me want to be a part of a movement that not only preserves our language but also brings us back to our cultural heritage,” she adds.

For Noha (18), it is “how each of the members helps one another in learning new words and sentences, decoding the language” that makes Yikvot special. “I believe I have built a sense of connection and belonging at Yikvot. I joined the club because I wanted to meet people who do not have a prejudice against the language,” she says.

Unseen yet unshaken

But Seerat’s journey has not been without its obstacles. As a young woman wearing the veil, she is constantly met with judgment from within her own community. Her success and visibility have been tainted by criticism that targets not her work, but her appearance and gender.

“If my life were to be chronicled,” she says, “it would be marked by constant remarks like ‘itni padhayi karke niqab hi pehn’na tha aur reading club hi chalana tha?’” (After all that education, you chose to wear a veil and start just a reading club?) — a refrain meant to belittle her ambition and dim her spark.

“For a year, I kept on pushing through and handling every aspect of Yikvot. I was not only a woman but a veiled one at that. Suddenly, my reading club fell into expectations of a religious entity, which was not my goal at all. People were joining my personal lifestyle with my work, causing distress. I believe the biggest setback of it all was to see different people coming up not to call me out or find any faults in the club, but to shame me for being an outspoken veiled woman and debating my hijab, perpetrating the same ideals that a woman who chooses to veil should not be in a public sphere,” Seerat says.

Despite these trials, Seerat stands resolute with form determination and a clear vision. Her dream is to transform Yikvot into a permanent, offline space — a cultural sanctuary where the young can learn and the old can guide, where Kashmiri literature, stories and emotions live on.

Valley’s lingering silence

Koshur, one of the oldest living languages in South Asia, belongs to the Dardic subgroup of the Indo-Aryan family. Despite its richness and resilience, the language has long faced systemic neglect.

In 1953, Kashmiri was officially removed from the school curriculum to “lighten the academic burden” on students. It was not until 2001 that it was reintroduced up to Grade 8 — yet even then, instruction remained patchy and symbolic at best.

By 2017, the then Jammu and Kashmir government made teaching regional languages, including Kashmiri, compulsory for grades 9 and 10 in areas where they are still spoken. But implementation has remained a major hurdle, with schools often ignoring the directive.

Dominant languages like Urdu, Hindi and English have taken center stage, pushing Kashmiri into the margins. This erosion is not merely linguistic — it is cultural, with each passing generation growing more detached from traditional poetry, storytelling and heritage.

Dr. Wahid Raza, a noted Kashmiri writer and columnist, highlights social media and unemployment as culprits. “People go abroad to earn a living, adopt the culture there, learn the local language and slowly start forgetting Kashmiri,” he tells TwoCircle.net.

Still, he believes there is hope. “As long as our dreams, our songs, our thoughts and our way of thinking live in our language, our language will stay alive.”