'History Doesn’t Shout, It Fades': In Fatehpur, How A Forgotten Tomb of Aurangzeb-Era Commander Becomes the Next Battleground

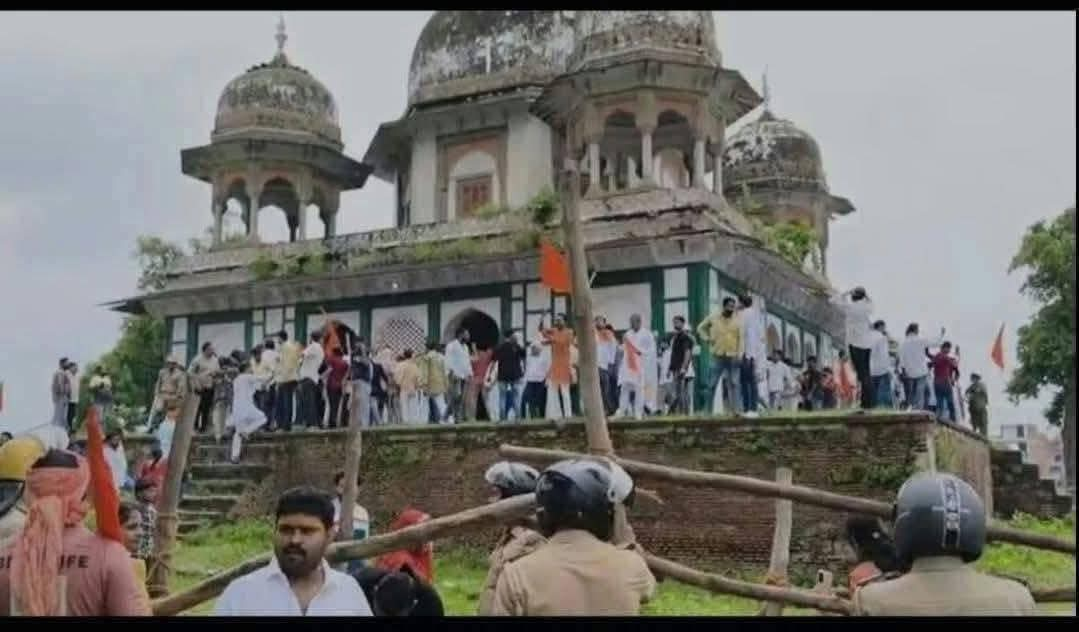

Fatehpur (Uttar Pradesh): Silence the narrow road in Abunagar. Broken bricks, burnt tyres and glass pieces are scattered. The gate to an ancient tomb is open. On a sweltering August 11 morning, the monument witnessed vandalism, Hindutva chants and waving of saffron flags. Nawab Abdus Samad Khan’s 17th-century tomb in Fatehpur, once forgotten by the world, was now thrust into a storm of religious assertion.

A crowd surged past barricades, led by members of right-wing Hindutva groups. With chants of 'Jai Shri Ram' echoing off its fading stone, parts of the mausoleum were vandalised. A saffron flag was hoisted on top of the structure.

Among the crowd was Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) District President Mukhlal Pal, urging people to reclaim what he claimed was the temple of “Thakurji Sanwaria Sahab Virajman”. The crowd comprising alleged members of the Bajrang Dal, the Math Mandir Sanrakshan Sangharsh Samiti and other Hindutva-aligned groups followed his call, claiming the "thousand-year-old temple has a Shivling beneath".

“We want to clean it for Janmashtami celebrations. There are religious symbols, Parikrama Marg and a temple well. The structure is not a tomb,” said Virendra Pandey, who is the vice president of the Uttar Pradesh wing of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP).

Inside the boundaries of this now-contested space are graves, which are marked, documented and named in the archives of history. “It is a centuries-old tomb with graves inside. The place is recorded in government documents. Are we now going to look for temples under every mosque and tomb?” said Mohammad Naseem, national secretary of the National Ulama Council, condemning the incident.

The Uttar Pradesh Police has registered an FIR against 10 named and 150 unnamed individuals after videos of the incident went viral. “We have videos and drone footage. We are identifying those who entered the tomb and damaged it,” said senior the superintendent of police, who confirmed that several sections of the Bharatiya Nayaya Sanhita (BNS), Criminal Law Amendment (CLA) Act and Public Property Damage Prevention Act have been invoked.

The tomb’s desecration followed a memorandum submitted to District Magistrate Ravindra Kumar on August 9, demanding removal of what was termed as “encroachment” and urging permission to perform religious rituals at the site.

Security has since tightened. Barricades line the perimeter. The police forces stand guard around the disputed zone. “The barricading has been done under the instructions of the District Officer,” confirmed Avinash Pandey, junior engineer of Nagar Palika Parishad.

However, for many locals, the sense of safety comes too late.

“We have grown up hearing from our elders how the Babri Masjid was demolished. Day before yesterday, it felt like the same scene playing out again. The crowd stormed in, as if they had come to tear it down, while the administration stood by and watched,” said Rameez, whose house is just steps away from the mausoleum.

His friend Kamran alleged, “The authorities knew what was going to happen. These organisations had announced their plans 10 days ago. There was deployment of the police force. Still, the incident happened.”

The silence from political quarters has added to the frustration, especially among young Muslims in Fatehpur. “The Samajwadi Party, the principal Opposition in the Uttar Pradesh Assembly, talks about PDA (Pichda - backward; Dalits (untouchables); and Alpsankhayak - minorities) but when it comes to supporting us on the ground, they are nowhere to be found,” said a local youth, refusing to be named.

In the wake of growing tensions, Pervez Khan, a Lucknow-based lawyer advocating for the preservation of Mughal-era monuments, warns of a pattern.

“From the Babri Masjid to the Nawab Abdus Samad tomb and even mazars (shrines) on the India-Nepal border, the Hindutva brigade continues to mock the very idea of respecting each other’s faith. The government watches like Nero as history burns,” he alleged.

A Tomb With a Name

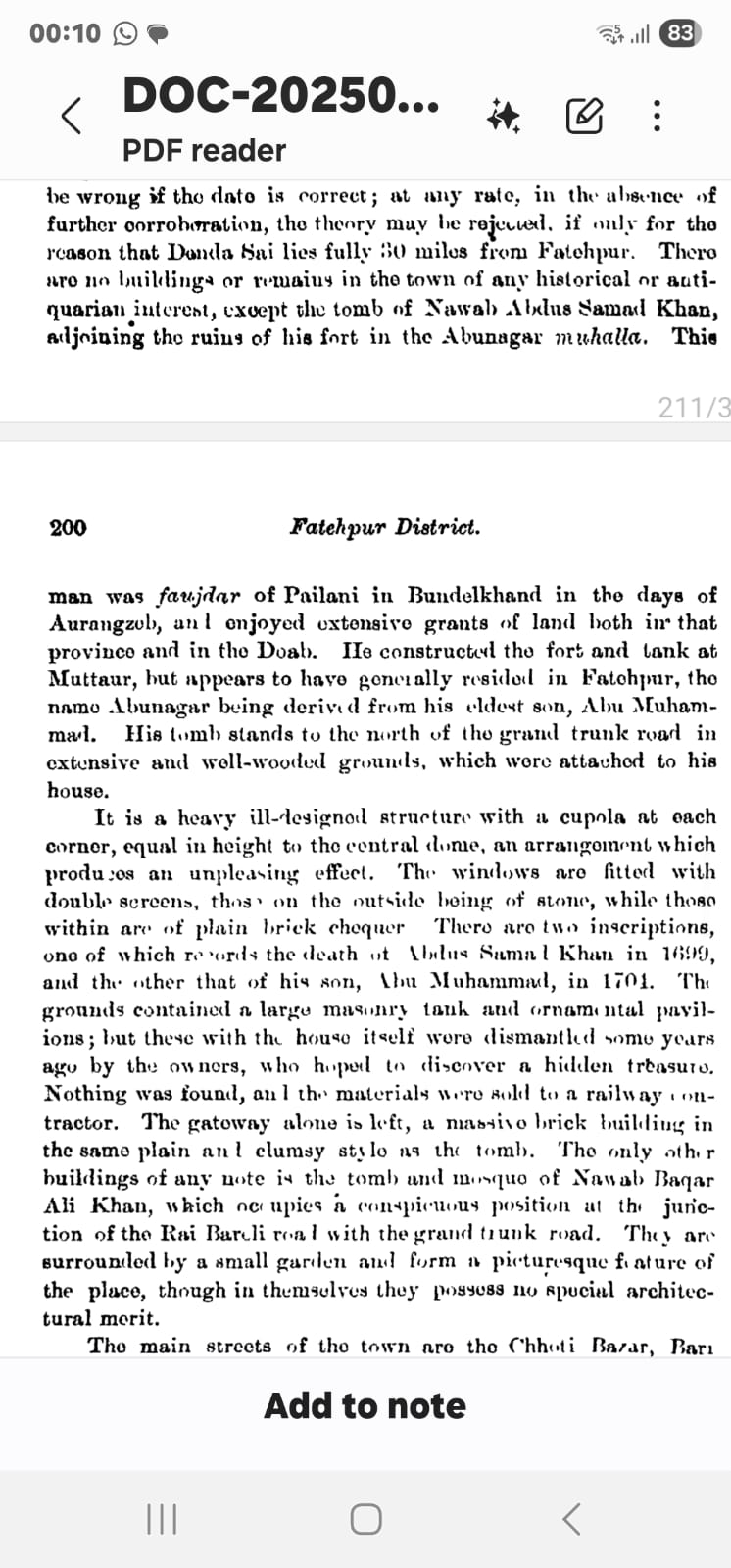

Abdus Samad Khan’s mausoleum is not a mystery wrapped in folklore. Its story has a mention in the District Gazetteers of Fatehpur, the Imperial Gazetteer of India and in architectural stone.

A 17th-century Mughal military commander of Emperor Aurangzeb, Khan was the 'faujdar' of Pailani in Bundelkhand. He died in battle against Prince Shah Shuja during the Mughal succession war. In honour of his service, Aurangzeb commissioned the mausoleum in Fatehpur, beside the ruins of his fort in Abunagar.

The tomb is officially recorded as “Maqbara Mangi” under Khasra number 753 and classified as protected national property. Though timeworn, the structure bears the hallmarks of Mughal architecture (minarets at each corner, a central dome, stone-carved window screens and inscriptions marking the deaths of Abdus Samad Khan in 1699 and his son Abu Muhammad in 1701).

“This mausoleum is famous for its stone carvings. It resembles the Taj Mahal in structure. Its minarets and engravings are a fine example of Mughal artistry,” said Mohammad Ismail Fatehpuri, a historian and author of the Tareekh-e-Fatehpur.

Once painted white, its walls have dulled. Moss cling to the surface. The fort that once stood nearby has been reduced to broken walls and rubble. Locals speak of people playing cards on the tomb’s steps, unaware of or unmoved by its past.

“People often spend time sitting there, chatting or gambling. They do not realise it is a historical monument,” a local resident said.

Encroachment too have sprung up around the area. Homes and shops now press in on what was once a vast and open compound. The large masonry tank and ornamental pavilions are long gone, demolished by people hoping to find hidden treasure. But nothing of that sort was found.

What happened with the tomb, locals say, is not merely a dispute over bricks and burial sites. They speak to the vulnerability of forgotten monuments and the people they represent.

In Fatehpur, the tomb stood still for centuries, untouched by time but worn by it. Now, its walls carry the marks of a different kind of erosion, not of weather, but of will.

As history is pulled into a tug-of-war between memory and political assertion, what remains is a solitary structure once meant to honour the dead, now made to answer questions of the living.

“History does not shout, it fades. And sometimes, we only notice it when someone tries to erase it,” said an elderly resident silently watching the barricaded site.