Out of Reach: The Quiet Ways India’s Digital Push Leaves Rural Women Behind

Musheera Ashraf, Twocircles.net

Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh: India’s digital story is often told through numbers. Millions of UPI transactions every minute. Seamless online services. Government schemes linked to apps. But far away from this vision, in villages where phones are shared and passwords are guessed, women continue to stand at the margins of a world that has shifted faster than they could follow.

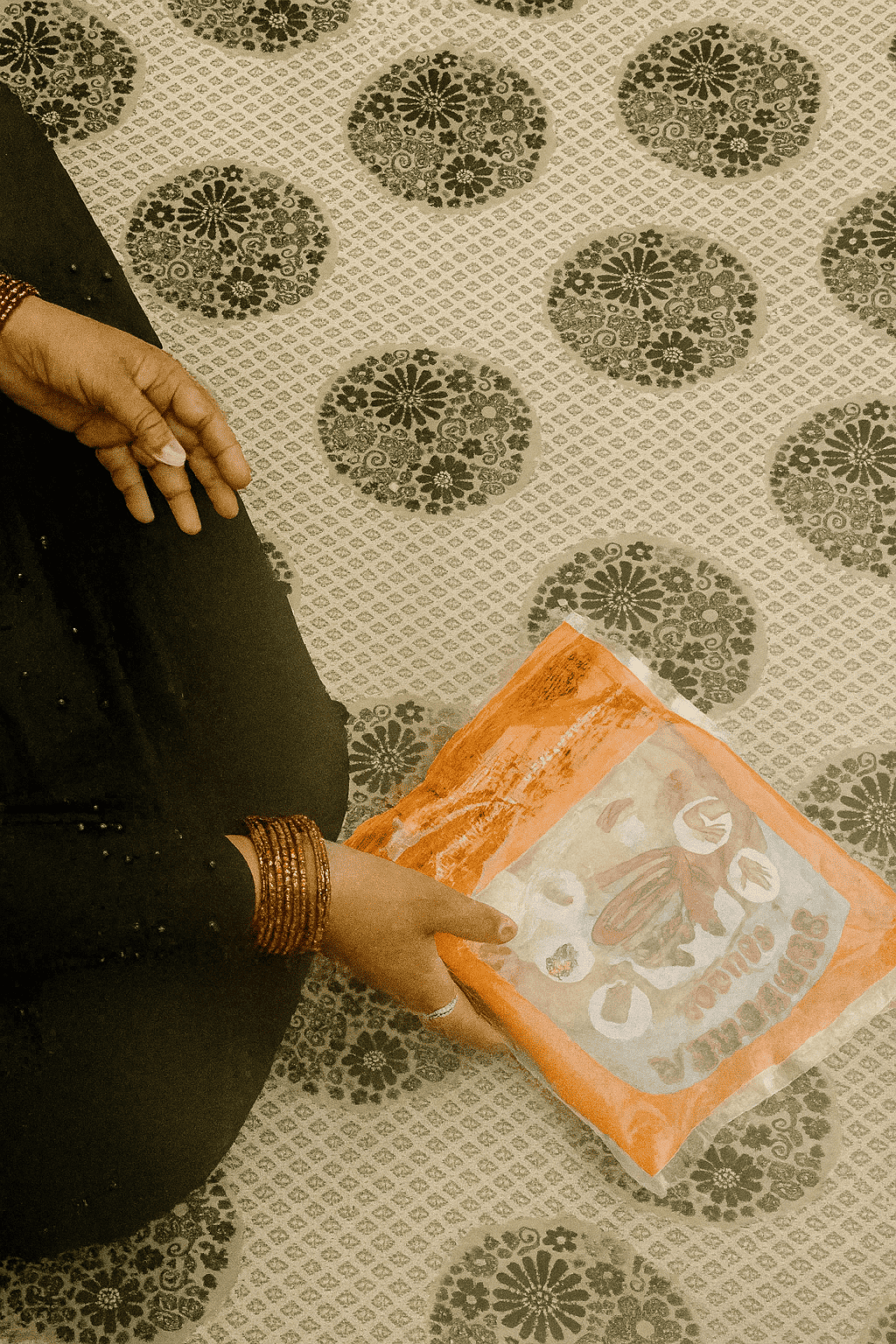

Musayyada, a thirty-five-year-old widow from a village ten kilometres from Saharanpur,

begins her day long before the city wakes. She boards a crowded tempo at dawn to visit the gas agency and ask why her cylinder subsidy has not come in three months. By the time she reaches, a queue has already formed outside the gate.

When her turn comes, staff tell her she will get the subsidy only if she buys a gas pipe that they insist is “mandatory.” She blinks in disbelief. “I changed the pipe just a month ago. I do not need it,” she says. The reply is flat, almost rehearsed: “It is mandatory. Even if you do not need it now, you can use it later.”

The pipe costs her two hundred rupees, roughly the cost of a day’s meals for her family of four.

The pipe costs her two hundred rupees, roughly the cost of a day’s meals for her family of four.

She carries a second-hand phone she purchased for twenty five hundred rupees, an amount she paid in instalments. “A phone is necessary now. Even if we skip a meal, we have to keep a phone,” she says. But she can only use it to receive calls and dial her daughter in another village. For everything else, she goes to the shopkeeper next door, even for the booking of the LPG gas. When asked how she remembers her daughter’s number without being able to read, she laughs shyly, “Akhir me do zero hain. (There are two zeroes at the end).”

Across rural India, women depend on neighbours, shopkeepers and family members for the most basic digital tasks. These hands, often male, do everything from booking their LPG cylinders to checking subsidy status. Trust fills the gap left by digital literacy, but it comes with risks.

In another family, an older woman kept receiving calls from strangers because a relative had used her number to register multiple online accounts. “I had no idea why people were calling me by someone else’s name,” 62-year-old Savitri recalls.

These are small incidents in the larger story of India’s digital push, but they show how easily the boundary between trust and vulnerability blurs.

Ten years into the Digital India mission, a gendered digital divide continues to dictate who gets to participate and who must stand outside the door. Nearly forty per cent fewer rural women own smartphones compared to men. Among those who own phones, many do not have control over them.

The divide becomes sharper in digital finance. Men are more likely to perform UPI

transactions by a gap of 13.7 percentage points. Official UPI statistics do not reflect this

difference because they are not broken down by gender. But those working in the payment's ecosystem acknowledge the imbalance. In 2023, a senior Google Pay official said women formed less than thirty percent of UPI users. In 2024, an NPCI (National Payments Corporation of India) representative repeated a similar estimate. Even these numbers drop further in semi-urban and rural areas.

A fifty-year-old schoolteacher in Saharanpur has the UPI app on her phone but refuses to use it. “What if the money goes to the wrong person? Who will return it to me?” she asks. She hands her phone to her son when she needs to make a payment. “If something goes wrong, I will be blamed. Better not to try.”

Fear is an unseen but powerful barrier. Many rural women say they prefer cash not because they lack awareness, but because they lack confidence. They have heard stories of fraud, passwords being stolen, transactions being reversed, and phones getting blocked after too many failed attempts. For them, digital mistakes feel heavier than physical ones.

Sita, a thirty-year-old newly married woman, sums it up simply. She has never booked her own LPG cylinder. “My husband does it. I do not have a phone,” she says. She uses his phone only to watch YouTube videos. “If something goes wrong, I will have to hear from everyone,” she adds.

The fear of doing something wrong is not imagined. It is shaped by years of being told to be careful, of being blamed for errors, of having limited room to experiment. Digital services, meanwhile, continue to expand. Schemes get linked to apps. Subsidies require updates. SIM cards need revalidation. Banks insist on KYC. LPG agencies ask customers to check status online. Each added step demands a confidence that many women have never been allowed to build.

Content creators online capture another layer of this reality. Recently, an Instagram creator, @lifeofpuja, said in a video that “no matter how much she works or how many followers she earns, she is still known as someone’s wife or daughter-in-law”. Rural women echo this sentiment in quieter ways. They often do not get recognition for learning new skills. Their identity is still tied to the household, not their digital abilities.

Sarvothanam, a Delhi-based organisation that works on online safety and digital trainings, says the issue is not just literacy but dependence. “Women who do not know how to use their phones rely on others. But the same people can misuse their access. Personal photos, messages, even their OTPs are shared without them knowing what is happening,” a member explains.

Despite the challenges, some change is unfolding. In a village near Deoband, Rahima, the

first graduate in her family, shares that she tries to teach basic digital tasks to her mother and the ladies near her home. I tell them how to open SMS messages, how to find saved contacts, and how to identify suspicious links. It is slow work, but it is work driven by care, not fear.

Parveen, a social worker who works with rural women in Saharanpur, Western Uttar Pradesh, says the path ahead requires more handholding, more community training, and more women-led digital learning groups. “Digital empowerment is not only about giving a device. It is about making women feel safe, confident and in control,” says a digital rights volunteer who works with rural women in western Uttar Pradesh.

India’s digital journey is racing ahead, but a part of the country is still walking carefully

behind it. The women in these villages are not resisting technology. They are navigating a

world that moved faster than their access, their confidence and their trust.

For them, autonomy is not measured in apps installed or transactions completed. It is

measured in quiet victories, answering a message without help, checking a subsidy status for the first time, or daring to press a button without fear.

And until these victories become ordinary, the digital future will continue to leave its women behind.

(Musheera Ashraf is a Laadli Media Fellow. The opinions and views expressed are those of the author. Laadli and UNFPA do not necessarily endorse the views.)