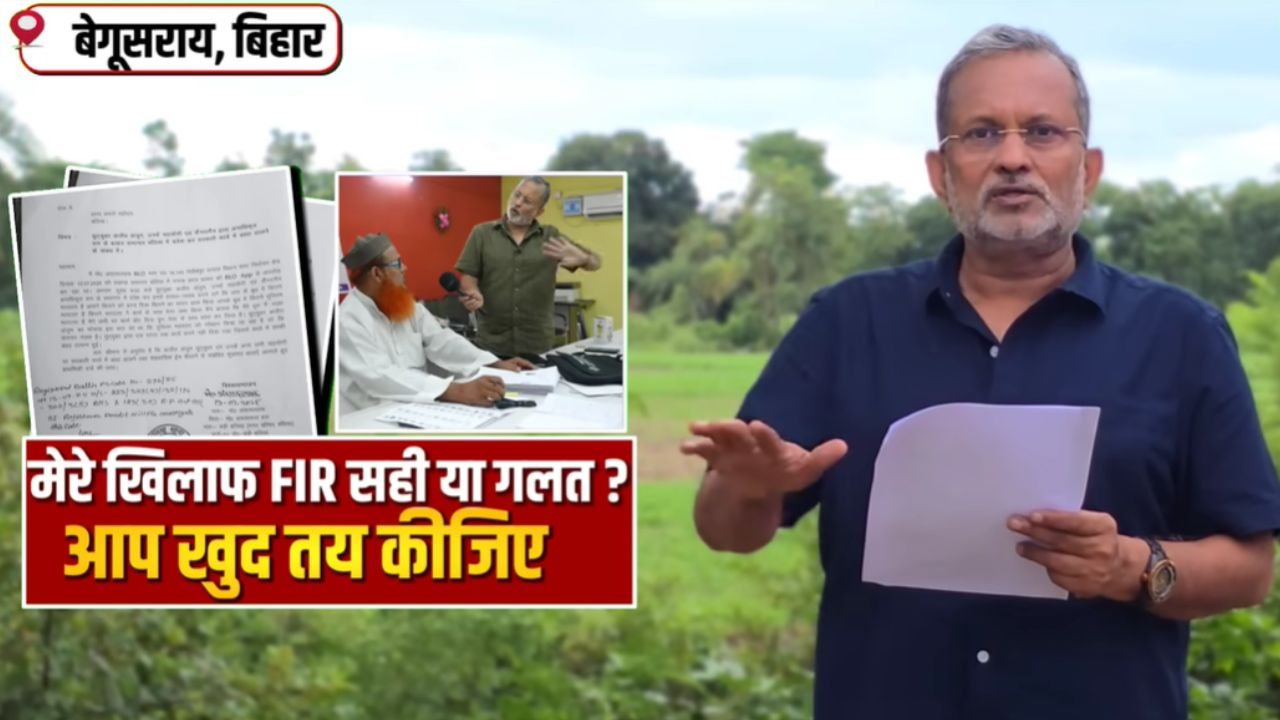

SIR or Scam? Bihar’s ‘Votebandi’ Hits the Poor, Muslims, Migrants - Question It, Get Booked

Sumit Singh, TwoCircles.net

Patna/Muzaffarpur/Bhagalpur/

But instead of scrutiny directed at the Election Commission of India (ECI), it was Anjum who ended up in the dock. A first information report (FIR) was lodged against him based on the complaint of a booth-level officer under serious charges such as criminal trespass, disobedience of orders and even promoting communal disharmony.

The case cites sections 223 (disobeying lawful orders of public servants), 329(c) (criminal trespass), 132 (assault or criminal force to deter public servants from discharging their duty), 196 (promoting enmity between different groups on grounds religion, etc.), 302 (uttering words, making gestures or placing objects with deliberate intention to wound the religious feelings of any person) and 3(5) (common intention in criminal acts) of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, or BNS along with section 123(3A) of the Representation of Peoples Act, 1951.

The backlash has been swift. Press bodies, Opposition parties and civil society groups are calling it what they believe it is a clear attempt to silence a journalist asking difficult questions. DIGIPUB News India Foundation described it as “an attack on independent journalism and the public’s right to know the truth". The Press Council of India backed Anjum, emphasising that “reporting facts is the primary duty of any journalist, and it does not come under the category of spreading misinformation".

Unfazed Anjum said the FIR was meant to intimidate him. He is no stranger to "state pressure". The former editor of national TV news channels now reaches nearly eight million subscribers through his YouTube channel.

The timing could not be more sensitive. Home to over 13 crore people, Bihar heads to the polls in just a few months. And the ECI's June 24 announcement kicked off an exercise that is turning into a nightmare for lakhs.

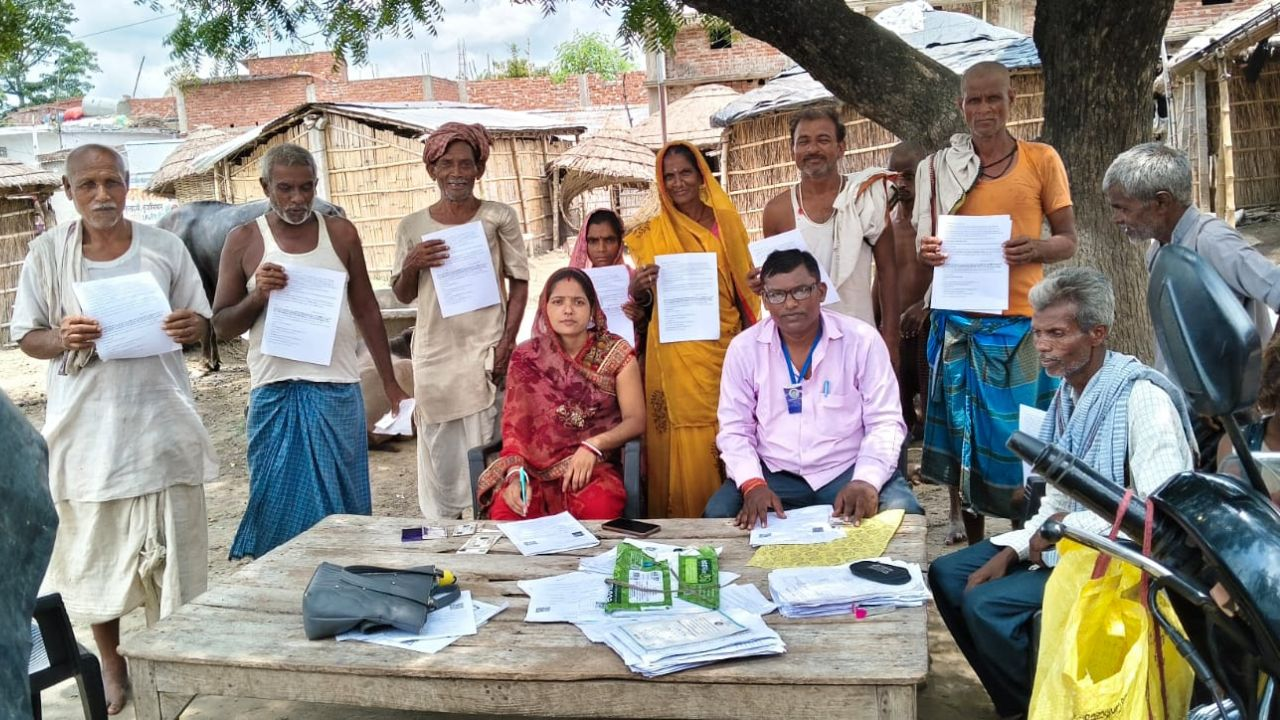

[caption id="attachment_452240" align="aligncenter" width="1280"] Under Special Intensive Revision (SIR), enumeration forms are being distributed to voters by BLOs in Bihar (Courtesy: Sumit Singh)[/caption]

Under Special Intensive Revision (SIR), enumeration forms are being distributed to voters by BLOs in Bihar (Courtesy: Sumit Singh)[/caption]

Under the SIR, all voters registered since 2003 must submit fresh documents to prove identity, address and citizenship. The deadline is July 25. The draft rolls go public on August 1. Final rolls lock in by September 30.

The ECI insists the process is needed to clean up the rolls, citing urban migration, unreported deaths and "foreign illegal immigrants". But ground realities tell a messier story. Critics say the exercise risks erasing millions, especially the poor, migrants and those on the margins. The documentation list does not even include Aadhaar, ration cards or voter IDs - documents most common among the poor.

On paper, 80.11% of voters had submitted forms by July 12. But many in remote villages say they have received nothing. Limited internet, digital illiteracy and patchy app performance have slowed progress.

For migrant workers, it is worse. Away in Maharashtra, Gujarat or Delhi, they miss home visits by BLOs. According to reports on July 13 citing "ECI sources", individuals from Nepal, Bangladesh and Myanmar have been flagged during verification, although no specific data was released.

Mostly schoolteachers and junior officials, the BLOs are juggling door-to-door form collection and digital uploads through the ECINet app, which often crashes in rural areas with poor internet connectivity.

The Supreme Court, hearing a bunch of petitions from different groups and individuals such as the Association for Democratic Reforms and MPs like Mahua Moitra and Manoj Jha, has voiced concern. Justices Sudhanshu Dhulia and Joymalya Bagchi questioned the document list and the 31-day timeline. Aadhaar and ration cards should qualify, they said. A national census takes a year. Yet on July 10, the Court allowed the SIR to continue, asking the ECI to respond to the concerns within a week.

Opposition parties, the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), the Congress and the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) or CPI(ML), have hit the streets. A statewide “Bihar Bandh” on July 9 was called to protest what they say is a calculated attempt to cut out Dalits, Muslims and the poor from the voter list.

Muslim women stand in queue to vote in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections in Bihar’s Seemanchal area (Courtesy: X/ECI)[/caption]

Muslim women stand in queue to vote in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections in Bihar’s Seemanchal area (Courtesy: X/ECI)[/caption]

In Seemanchal, voters are being asked for land deeds or birth certificates they have never had. Aadhaar is accepted in cities like Patna, but not in nearby villages, deepening the divide. Elderly voters, displaced by floods or poverty, are in despair.

In Bhagalpur’s flood-prone belt lives Ram Prasad, a 45-year-old daily wage worker whose home has washed away twice. His only document is his Aadhaar card - his ticket to vote in 2024. Now it is not enough. “I voted last year with my Aadhaar. Now they say it is useless. I was born here. My father was born here. What proof do they need?” he asks.

Bhagalpur floods drowned many homes last year. Ram was among those affected. His deadline to submit proof ends in days. He fears being erased from the voter list.

[caption id="attachment_452242" align="aligncenter" width="1280"] A government school in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur where people cast their votes during elections (Courtesy: Sumit Singh)[/caption]

A government school in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur where people cast their votes during elections (Courtesy: Sumit Singh)[/caption]

Meena Devi, a 38-year-old domestic worker in Muzaffarpur, is in the same bind. She voted in 2024 with her Aadhaar. Her name is not on the 2003 list. Born in a village in 1987 with no birth registration, her parents long gone, Meena now faces exclusion. “I have lived here my whole life. I work, I vote. Now they say I do not exist.” she says.

In Gopalganj, 30-year-old construction worker Anil Kumar is equally trapped. Born in 1995, he too relied on his Aadhaar to vote. But without a birth certificate or his parents’ papers, his voter status is now at risk. “My parents never had any documents. If Aadhaar does not count, how do I prove I am an Indian?” he questions

Patna’s Mahavir Mandir and Jama Masjid stand side by side, embodying harmony in diversity (Courtesy: Sumit Singh)[/caption]

Patna’s Mahavir Mandir and Jama Masjid stand side by side, embodying harmony in diversity (Courtesy: Sumit Singh)[/caption]

The inconsistencies are piling up. Amid rising protests, the Bihar Chief Electoral Office ran full-page ads on July 6, saying even incomplete forms will be accepted and verification can rely on local checks. Critics saw it as a reluctant climbdown.

The shadow of the controversial National Register of Citizens (NRC) allegedly hangs heavy. The ECI’s talk of “illegal immigrants” without data has stirred anxieties. Migration is part of Bihar’s history - across states, even borders. The requirement for citizenship documents is seen by many as a loaded ask.

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee called the SIR "more dangerous than NRC". The BJP, in turn, accused Opposition parties of creating fear to "protect vote banks".

Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar (Courtesy: X/ECI)[/caption]

Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar (Courtesy: X/ECI)[/caption]

Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar responded on July 5, saying, “A detailed investigation of the voter list and all details of the voters was not done after 1 January 2003… Nearly every political party complained about issues in the authenticity of the voter list and demanded updations.”

In Bihar, over 77,000 BLOs, joined by 20,000 new appointees, are tasked with verifying 50 households a day to meet the ECI’s target. On July 3, the Commission announced a Rs 6,000 honorarium per BLO and supervisor.

Limited internet access and scarce cyber cafes pose significant challenges for people in rural areas of Bhagalpur to meet the documentation requirements (Courtesy: Sumit Singh)[/caption]

Limited internet access and scarce cyber cafes pose significant challenges for people in rural areas of Bhagalpur to meet the documentation requirements (Courtesy: Sumit Singh)[/caption]

The SIR guidelines allow BLOs to flag suspected foreign nationals under the Citizenship Act. Experts warn this opens the door to profiling and errors, especially with coercive form collection and key IDs like Aadhaar excluded.

A report by The Reporters’ Collective highlighted that the SIR began despite a voter list update in January 2025, raising questions about timing and motive.

Bihar is not alone. Allegations of voter roll manipulation marred the 2024 Assembly polls in Maharashtra, Haryana and Delhi. In Maharashtra, Opposition leaders claimed 39 lakh new voters were added and 8 lakh removed in just five months.

Leader of Opposition in the Lok Sabha Rahul Gandhi called the results "glaringly strange", alleging a "five-step process" of manipulation. The ECI rejected the charges as "absurd", citing transparency with parties.

But for Bihar, the pattern, many feel, appears to be familiar - swift roll changes, pre-poll timing and stringent documentation. The proximity to elections only heightens the stakes.

An election poster of the BJP with PM Modi’s face in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur (Courtesy: Sumit Singh)[/caption]

An election poster of the BJP with PM Modi’s face in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur (Courtesy: Sumit Singh)[/caption]

Political scientists and rights advocates are alarmed. Human rights lawyer Dr. Anjali Sharma calls the SIR a "bureaucratic trap". “Voting is a constitutional right, not a paperwork privilege. This process mirrors the NRC’s dangers, shifting the burden of proof onto the most vulnerable,” she says.

Activist Kavita Kumari, who works with migrants, fears profiling. “The term ‘illegal immigrant’ creates fear. It targets Muslims and migrant labourers,” she says, recalling Assam’s NRC, where 1.9 million people were excluded over clerical mistakes.

Congress spokesperson Salman Anees Soz summed it up, “You allow people to vote in 2024, then months later say their documents are invalid? That is outrageous. This government is creating barriers to voting, not removing them.”

As Bihar inches closer to its 2025 elections, the SIR is no longer just an administrative exercise. It has become a litmus test for India’s democracy, raising a fundamental question - who gets to vote, and who gets left behind?