Aamirah Thayibah, TwoCircles.net

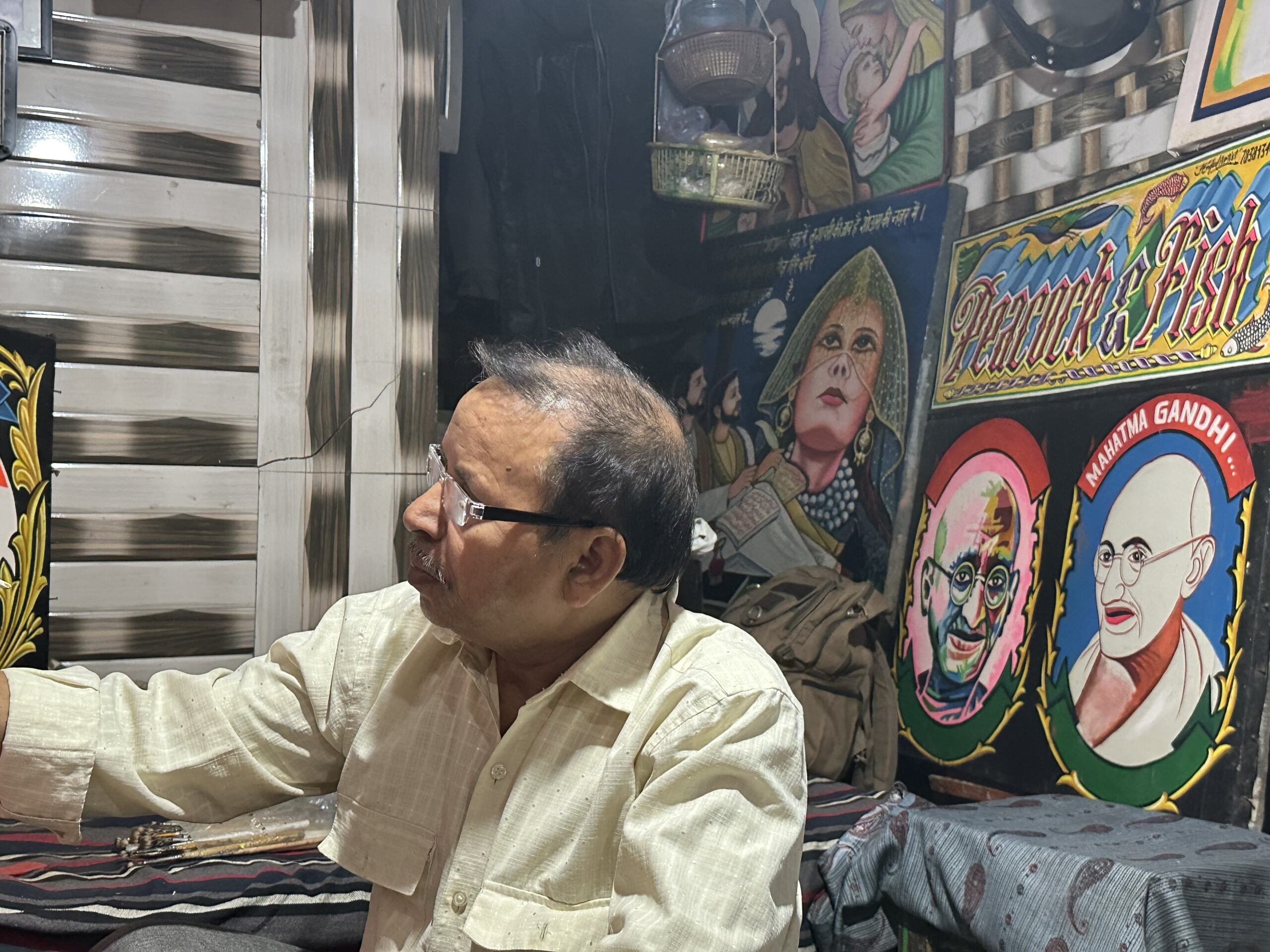

New Delhi: Behind a frayed curtain, a modest and dimly lit room in a narrow alley in Old Delhi houses a treasure trove of art. Canvases lie stacked, paint bottles rest on the floor and a 71-year-old artist is hunched over his latest creation. This is painter Kafeel Ahmad’s world.

Popularly known as Painter Kafeel, he is crouched on a low stool, his gaze fixed on a half-finished signboard that will soon be sent abroad.

“This one is going to the Netherlands,” he says, with his fingers tracing the vibrant and swirling typography on the canvas, which pulses with colour.

At a time when glossy, mass-produced vinyl prints are replacing India’s once-iconic hand-painted street art, Painter Kafeel’s work remains steadfast and reminds craftsmanship and soul that traditional sign painting embodies.

His journey from a small-town boy at Bareilly in Uttar Pradesh to an internationally recognised artist, showcases his determination to stay true to his art in an increasingly digital world.

Born in a small town of Anola, Kafeel’s early life was far removed from the buzz of India’s bustling capital. His days were simple – school in the morning, afternoons spent helping at his father’s general store and evenings watching and observing the canvas work of his neighbour, Shabir Raza Khan, a local painter.

“In school, my teachers always pushed me to improve my handwriting in Urdu and Hindi. Soon, I was the best in my class,” recalls Kafeel recalls in nostalgic voice.

It was his father who recognised his potential and handed him his first job, which was writing neat labels for the jars in the family store.

“I wrote labels for saunf (fennel seeds), dhaniya (coriander), zeera (cumin) and sugar candies,” he smilingly says.

Word of his near-perfect handwriting spread, and it was Khan, the neighbourhood artist, who gave him his first set of paints and a brush – sparking the passion that would become his life’s work.

“I spent hours just watching the paint. When I finally picked up the brush, it felt like an extension of myself,” he remembers.

However, by 1980, Kafeel’s circumstances had changed. His father was no more, his family’s business had crumbled and with no support from his elder brother, he packed his bags, took Rs 500 and cycled to Delhi with nothing but his paints and a dream.

“Not having family support was not easy. But looking back, they did right by me – I found what I was truly passionate about: painting,” he says.

Delhi became Kafeel’s canvas in those early years. Decorated with tassels and a sign that read “Painter Kafeel – Artist (Urdu, Hindi, English)”, his bicycle took him from one end of the city to the other.

“I cycled from Jamnapar (Trans Yamuna Region or Northeast Delhi) to Purani Dilli (Old Delhi), looking for shopkeepers who needed signs,” Kafeel remembers. Summers were his busiest time, with cold drink stalls, new businesses and weddings all requiring his artistic touch.

Painter Kafeel soon became a well-known name in the city. His hand-painted signs adorned shopfronts, billboards and cold drink advertisements across the city.

Kafeel refined his craft under the guidance of Meena Bazaar’s Painter Faiz. For 19 years, he apprenticed under him before opening his own studio in Matia Mahal.

The 2000s brought a slow yet noticeable shift. With the rise of air-conditioned malls and the proliferation of vinyl banners and flex boards, the charming and handcrafted signboards of Delhi were slowly being replaced by cheaper and shinier alternatives.

“It was obvious. These new boards were faster and cheaper than paying an artist,” Kafeel says with a note of sadness.

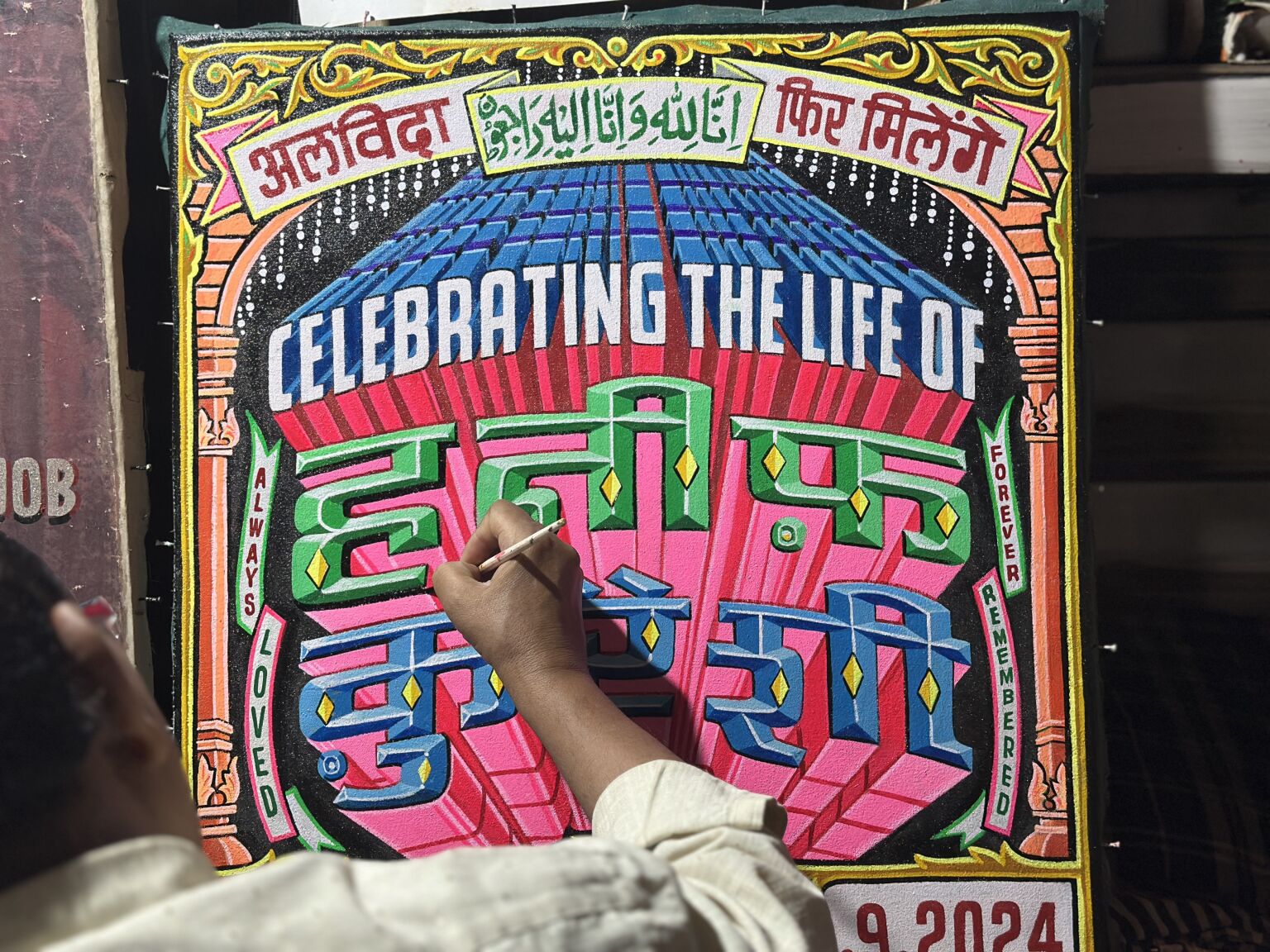

However, just as it seemed the old craft was fading into obscurity, he crossed paths with Hanif Qureshi, a street artist and documentarian. The latter was working on HandpaintedType – a project to document traditional sign painters across India. Kafeel’s bold and angular Devanagari script stood out.

“Hanif bhai had a special eye. If he chose me, that had to mean something,” he says, chuckling.

Through HandpaintedType, Kafeel’s unique font was digitised and eventually licensed by global giants like Google, Forbes and Starbucks. Once confined to the narrow lanes of Delhi, his work now reached across the globe – from Paris to Perth.

Before the project, a signboard commission might have earned Kafeel a few hundred rupees. Now, international clients pay anywhere from Rs 7,000 upwards, with his most recent commission selling for Rs 17,000 (around 200 US dollars).

“There is a real appreciation for typography abroad. People who want quality still know where to look,” Kafeel says.

In a corner of his small studio, a desktop computer sits covered in dust. Kafeel briefly experimented with digital tools and realised that nothing compares to the feeling of a paintbrush in his hand.

“It just does not feel the same when I do not touch my work,” he says, holding up a canvas to the light. The eyes of a painted portrait glisten, as though they are alive.

“My goal has always been to create something extraordinary. I do not want to imitate others. I want my work to be worth imitating,” Kafeel adds with a smile.

Despite his attachment to traditional methods, he has found a way to blend the old and the new. A black tripod stands ready next to his current project, showing his growing Instagram following. Time-lapse videos of his painting process now bring him orders from all over the world.

“For a while, my son handled my Instagram. But I prefer doing it myself as he is terrible at spelling the captions,” he laughs.

As he moves carefully among the scattered canvases and jars of paint, Kafeel pauses to wipe his hands on a rag. Outside, the typical noise of Old Delhi – motorcycles honking, vendors calling – fill the air, but inside, Kafeel remains focused on his work. The brush strokes are steady, the colours vibrant.

He knows he is part of a vanishing world. Many of the painters he once worked alongside have passed away, and others have laid down their brushes. The younger generation, he observes, has turned to modern careers in gleaming cities.

However, Kafeel remains hopeful.

“I believe the need for artists will never disappear. There will always be quality art for those who seek it,” he says.

On his latest canvas, the curves of Hindi and Urdu letters take shape, their outlines drawn in black ink. The piece reads “Hanif Qureshi”, with the dates “12 October 1982 – 22 September 2024” beneath it. It is Kafeel’s tribute to his dear friend and mentor, the one who helped bring the two artists together.

A fresh roll of canvas waits in another corner of the room, with its edges nailed to a frame. Another project begins. For Painter Kafeel, the art of staying relevant is just a brushstroke away.