By Siddhant Mohan, TwoCircles.net

Last year, BRD College in Gorakhpur shot to worldwide notoriety after dozens of children died due to a critical failure of oxygen. What followed was one of the most intense media investigations into the hospital, its staff and its officials. No wonder then, that one of the first things that the administration did was to shut its doors to the media and hide behind press releases, counter-narratives and the usual bureaucratic procedures. A year on, however, it has emerged that factors which caused the deaths are far from solved and even now, the hospital is indulging in hiding its gaps instead of addressing them. Siddhant Mohan spent many days in and around BRD Medical college, speaking with patients, families, doctors and other staff to find out what is going on in the hospital a year after the deaths. In a two-part investigation, he exposes the good, the bad and the unchanged aspects of the hospital. Here is Part One of the investigation.

When the train stops at Gorakhpur railway station, one can smell the city which saw one of the most surprising political changes of this year. Vendors, rickshaw pullers, autorickshaw drivers and every other person talks about ruling Bharatiya Janata Party losing the Loksabha by-poll in Gorakhpur— a seat which Yogi Adityanath held for decades—to Samajwadi Party.

But another subject they do not forget to talk about is the Baba Raghav Das Medical College or more popularly known as “BRD Medical College”. Pradeep Saini, a 34-year-old rickshaw driver, said, “Even if Baba (Yogi Adityanath) lost the election this year, he has made sure that everything is good at (BRD) Medical College. He goes there in his every visit to Gorakhpur to make sure that what happened in August 2017 is not repeated,” while taking me to my place of stay at Gorakhpur.

It was a disaster at Medical College on the night of August 10 and 11 in 2017. A critical shortage of the liquid oxygen at the Medical College led to the death of 36 children in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and Paediatric Intensive Care Unit of Nehru Hospital associated with BRD Medical College. The lesser reported death number is of adults. Around the same critical shortage period, about 18 adults lost their lives, more likely due to a shortage of oxygen, in the Medicine ward of the hospital. If sources at the medical college are to be believed, the Medical College as well hospital most likely manipulated and hid the number of deaths that occurred that night in the Emergency Ward of the hospital.

Following the incident, three separate investigating committees were constituted under various powers, and surprisingly, all refuted the claim that the shortage of oxygen had anything to do with the deaths. Committees went a step further claiming that there was no particular shortage of oxygen which could be termed “critical”. But committees held Pushpa Sales, the firm responsible for supplying oxygen, and store manager responsible for deaths and both were put behind the bars along with several doctors of the medical college. Siddharth Nath Singh, a BJP leader and health minister in the state, showed his apathy for human values by dismissing the deaths, saying, “Children usually die in August.”

So one must wonder that things would have been improved or changed at BRD Medical College—at personal as well as administrative level—to minimise the damage to human lives. To witness the same, we conducted an investigation across several days including interviews with various officers, doctors, sources, and journalists, and on a broader scale, we could possibly infer that things at BRD Medical College as well as associated Nehru Hospital is standing behind a black curtain to regulate and censor the incidents as well as practices going inside the premises.

From January 2018 to July 2018, about 89 children suffering from encephalitis lost their lives out of total 278 admitted. Until the end of June, 1,049 children had lost their lives collectively, and by the end of July, this number reached about 1200.

Until the oxygen shortage controversy in August last year, the Medical College used to give out death numbers to media, the municipal department as a public record. But it soon stopped doing so. So for media, the verbal quotes from the sources at the medical college are the only possible way to get into the College’s system.

Soon I entered the Medical College on a rainy morning, I saw a freshly made road in the premises—which was still emitting the heat of the fresh tar—and the walls painted with the saffron colour. Taking a left turn from the entrance, I entered into Nehru Hospital, which showed the high dependency of nearby districts and villages over a single hospital. The plan was to completely understand the admission, checkup and discharge procedure at BRD medical college, especially of paediatrics department, to witness the loopholes. I could see one enquiry counter right from the entrance, but there was no one inside. When no one showed up for about 15 minutes of waiting—during busy working hours at a government hospital—few people sitting by it told me that they had rarely seen anyone there. During random conversations with people, people around said that they were there from Kushinagar, Maharajganj, Deoria, Ballia, Mau, Siddharthnagar districts of Uttar Pradesh, as well as from Siwan and Bettiah district of Bihar, revealing the high dependency of individuals on BRD Medical College.

Ramesh Kumar Agrahari, a 42-year-old resident of Mau, came with his wife at the medical college after her repeated complaints of back and stomach pain. His wife, Phulmati, was sleeping alongside him wearing a yellow coloured saree. Agrahari said, “I got her examined at the district hospital in Mau, but she did not go any better. From Mau, we can either go to Banaras (Varanasi) or come to Gorakhpur for better treatment, but treatment, as well as stay cost, is high in Banaras, so we decided to come to Gorakhpur.”

Not only Agrahari, many counted the same point of cheaper facilities at Gorakhpur than Varanasi or Lucknow as the reason behind them choosing this as the treatment centre. Many told that there were not enough facilities and staff at the government hospitals in their district, which is why they chose Gorakhpur.

Pramila Devi, a 68-year-old housewife from Deoria district, came to the hospital with her 13-year-old grandson to have him examined for continuous fever. Devi was sitting by the same enquiry counter, while her husband had the sleeping grandson in the lap. When I touched the forearm of his grandson, I noticed he had an extremely high fever. Devi told me, “At first it was just a fever, but now whenever fever comes, he nearly faints.”

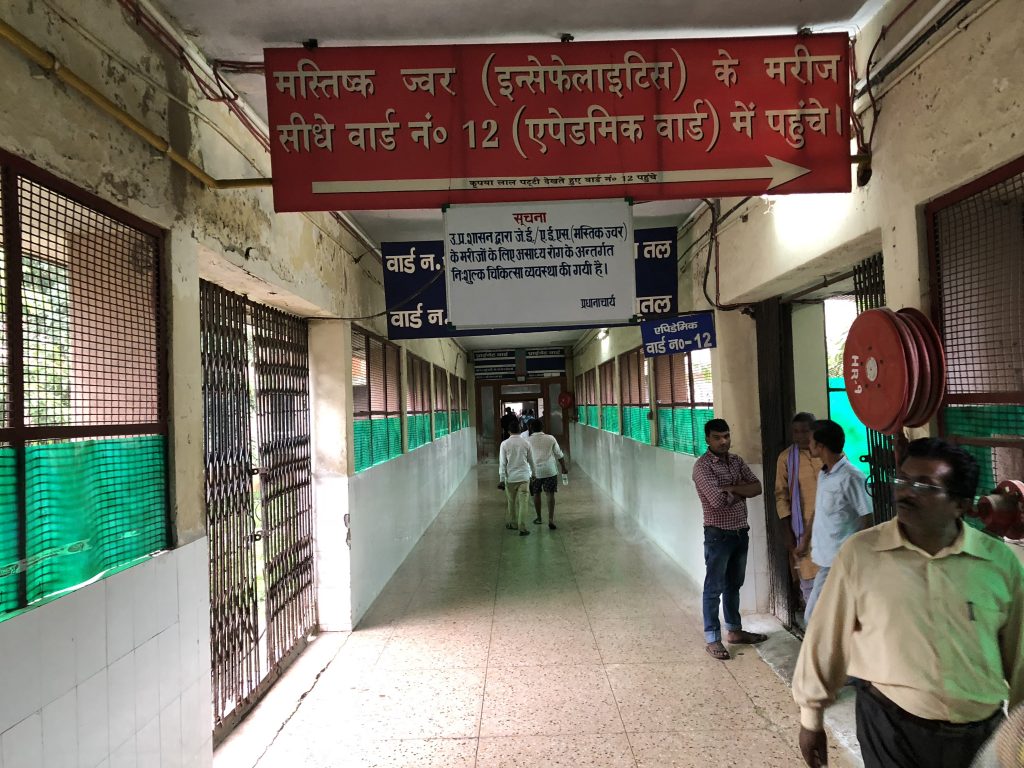

From the entrance of the medical college from the main road until the ward entrance, banners have been put asking people with encephalitis patients to go directly into ward number 12 or Epidemic Ward, as if most of them are aware of their patient is suffering from one. Devi said that a couple of the attendants told her to take the grandson directly into the ward number 12 but she did not know where it is, and also she does not have the idea if he is suffering from encephalitis. This was the reason she was sitting by the enquiry counter, while her son—also the father of the sick child—went to clear the confusion about admission and examination.

Located after several tries, I found a way to NICU and PICU of the hospital, where most of the deaths have occurred last year due to the scarcity of oxygen and are still happening. The passage to connect these intensive care units with the hospital’s main lobbies was supported by public toilets alongside. I could see human excreta as well as discarded sanitary pads/cloths soaking up in the rainwater out in the open just few meters from NICU and PICU.

At my first try, I could not go into NICU and PICU. There was an unusually high number of security guards at the gate of these ICUs. Patient attendants standing outside of the gate told me that such guards came up after August deaths in 2017. Rekha (32) said, “My second son is admitted to PICU. He is getting better so I tried to click his picture to send it to my sister. Soon I pulled out my mobile phone, the staff started scolding me that why I was clicking pictures,” while smiling. “Why would anyone want to click the photograph his / her son? Should there be any specific reason for that?”

Ward number 12 or Epidemic Ward was filled with nurses and doctors who became kind of hostile when they noticed me taking several rounds of the ward and looking into their files. Later, Mahima Mittal, the head of the paediatrics department, and Ganesh Kumar, the principal and dean at BRD Medical College, allowed me—after hours of pursuance—to take rounds and pictures of the concerned wards and units which have been showing the highest number of deaths since past several years. To take control, a couple of resident doctors were assigned to take me to these units and to tell me things I was not interested in.

First I was taken to the newly made ward number 11 of 76 beds which was not even started yet. I was told that this ward could reduce the load at the paediatrics unit of medical college but the ward had not started yet. By the time this copy was filed, the ward was still being prepared for regular purposes, however, it was already inaugurated by the authorities as one could easily notice the ribbons and decorative items. “It is just new. We are hoping that more children will come in this,” said the resident who was accompanying me. “Where are the children now, if they are supposed to be here?” I asked. To this, the resident replied, “They are being treated, of course, but we have more facilities here. Things have changed since August 2017.” Obvious question came up “So there were no such facilities here earlier to August 2017?”, the resident hesitatingly smiled, did not say anything and took me to the ICUs.

At the entrance of PICU, I was asked to wear a shoe cover—a necessary practice in intensive care units—but it was a different scene inside. As it looked clean and ‘protocol-following’ unit, it was filled with the attendees and none of them were wearing any shoe cover or protective masks, even when several of the admitted children were put on a ventilator, a vulnerable condition to get infections.

On the bed sheet of a severely malnourished child, who was just taken out of the ventilator, I could see stains of blood and wound exudates. And worse, it was not just a single case in the PICU. One could notice blood stains, excreta stains, spots made by exudates—risking infections—on several beds where patients did not have any wounds or any cause that could lead to such bed sheets. One attendant came to me and said, “Actually, these beds were like this even before our child came up. We asked to get them changed, but we fear that if we pursue more, they will not take care of our child.”

One staff at PICU anonymously, told, “Critical care code is not so much in practice here. If checked, patients could be dying because of the infections coming in from the dirty mattresses and beds, who knows.” Despite an occupancy of about 40 patients, I could notice only four staff nurses and ward boys. When raised it with the resident—who was kind of “following” me to my every talk—he said it is indeed less for a such a big hospital. He even went to say, “We have beds, what we lack is trained medical staff,” reiterating the same crisis which Principal Ganesh Kumar told me back in April this year.

I met seven-year-old Kajol and her mother Gyanti from nearby Rakhat village of Chauri Chaura in the newly-made paediatric ward. Kajol, a patient of encephalitis—or Acute Encephalitis Syndrome (AES)— was discharged from PICU just three days back. Gyanti, who was worried because her daughter was still in a COMA and was being fed through a pipe, revealed that she had to buy several medicines from outside of the hospital, contrary to the claims of authorities that AES patients are being provided medicines inside the hospital free of cost. Gyanti’s claim disturbed the resident doctor, who has been accompanying me, and he fired over her, “Which medicines did you have to buy from outside? You must be getting all from inside,” and he turned towards me, “She does not know exactly, or maybe she is confused.” While the doctor was trying to make me aware of the fact, Gyanti pulled out all the medicines from a bag and showed me exactly the same ones which she had to buy from outside.

Surprisingly, she had to buy Piracetam syrup—a routine drug which is given to AES patients to improve brain function—from outside of the medical college. Gyanti said, “When my daughter was in ICU, there were few more medicines which I had to buy from the medical stores.”

It was not a single case in the same “newly established ward”. Many of the patients I met complained that they had to buy many drugs from outside. According to the rules, district hospitals and state-run medical colleges have to maintain a good stock of medicines, but at BRD medical college, such rules have been put aside.

The resident doctor accompanying me tried to take control of whatever I found in these wards. He said, “Some medicines they get to buy from outside, but they get many from here.” When I pressed that attendees are buying neurotropic drugs, a routine and essential ones, from the shops, the doctor said, “It is not that a big deal.”

In the same section of the medical college, there was NICU as well, which recorded the highest number of deaths in August 2017. On the horrifying night of August 10 and 11 last year, parents whose children were kept in NICU were called and were given resuscitator—a device to manually pump oxygen in the lungs—to keep their neonates breathing. Evidence showed that at least four to five kids were put on one neonatal warmer, which is to be used for a single baby.

The resident accompanying me took me to the same level in the building where NICU was located but told me, “You cannot go in. Even doctors are not allowed to go in there.” I asked, “Not even doctors? Really?” He did not say anything. Even after several tries, I could not get into neonatal ICU, however, it revealed minutes after why one was not allowed to go into one. Another doctor, who saw me taking rounds of the ward, came to me when I was alone and said, “If you are searching again for oxygen scarcity, yet again, let me assure you that it is not the case this time. But condition inside NICU has not changed since August.”

The doctor requested anonymity and said, “They rarely allow anyone in there. Because the practices are not up to the code of treatment. We still keep four-five neonates on bed warmers.” For the confirmation of what happened last year at BRD’s NICU, I showed the doctor the photographs provided by my sources. There were pictures of parents using resuscitator and warmers full of babies, several of whom were already dead. The doctor said, “Yes. Warmers still get full like this. Babies still die. But oxygen is not the reason.”

I was into much-debated Epidemic ward (12) where encephalitis patients could go directly. There was a separate OPD setup inside the ward, and thanks to the newly made paediatric ward discussed above, the ward had a lesser number of patients.

I met Satya Devi of Karjahan village of Ramnagar, whose 16-year-old daughter Reena was admitted in the hospital on July 6 following the symptoms related to AES. While Satya Devi was talking to me, she was also holding her unconscious daughter by tilting her body to the left side. She said, “She has been given food from the nose pipe. I have to tilt her to let the food settle.” Prior to BRD Medical College, she took Reena to a CHC in her locality, but she could not be treated there. She immediately took her to BRD Medical College for treatment, where Reena was kept in PICU for several days, and shifted to the wards just a week ago. Devi told me, “In my locality, back at the village, several people have lost their sons and daughters here at the medical college. One has died in August 2017 due to lack of oxygen, but I had to get my daughter treated, otherwise she would have died anyway,” while discussing the necessity to come here.

In the ward, some beds were lying vacant, giving a kind of a relief to the patients as well as doctors. In the same ward, I managed to count six patients suffering from AES as well as five patients of meningitis. Several patients were suffering from malnutrition, followed by developmental delay, and the third largest number of the patients were of sepsis, commonly known as blood infection.

For the obvious reasons, another doctor was again put by my side for the ward visit.

This time I raised the question with the doctor accompanying that why was there was an unusually high number of meningitis cases, “this is the season,” he replied.

However, it was not the case that meningitis patients were increasing at BRD Medical College unless authorities were not trying to minimise the encephalitis cases by labelling them as meningitis. One paediatric doctor, requesting anonymity, confirm this rumour to me. Catching me alone in the hospital corridor, he told me, “You were asking about meningitis, no? The thing is that indeed meningitis cases happen in this season, but for the medical college, encephalitis is always the bigger problem. There are around one or two cases of meningitis.”

He further said, “But the pressure from the government is immense. The college has to achieve lesser encephalitis death, so the instruction has been passed on to report few encephalitis cases as meningitis, so at least authorities would stop pinging every time.”

When I talked with the senior resident accompanying me, he said, “Actually, AES is like an umbrella and meningitis comes under it.” I asked, “So, why are you not labelling it as AES just like you are doing with other encephalitis patients?” He did not say anything.

In the second and final part, we look at how the administration is both trying to fight the menace as well as cover up any possible investigation into it’s affairs. As we find out, they are failing ok both these fronts.