The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) study further found that meals in schools do not just contribute to education, but influence students’ “fertility decision” later in their lives and give them access to health care.

Niladry Sarkar | TwoCircles.net

WEST BENGAL — Stunting among children aged five years and below has increased in seven districts in West Bengal, as per the latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), published in November last year. The numbers of wasted and underweight children have also increased in 10 and nine districts respectively. Kolkata, the capital of West Bengal, has embarrassingly seen a rise in all the categories.

Wasting (low weight in terms of height) increased in Kolkata by 11.9 per cent, in Dakshin Dinajpur (5.7 per cent), Darjeeling (9.3 per cent), Howrah (6.7 per cent), Hooghly (1.5 per cent), Jalpaiguri (0.6 per cent), Nadia (6.9 per cent), Bardhaman (2.5 per cent), South 24 Parganas (1.1 per cent) and Uttar Dinajpur (2 per cent), found a study that compared the numbers of NFHS-4 and NFHS-5.

The study titled “Prevalence and change detection of child growth failure phenomena among under-5 children: A comparative scrutiny from NFHS-4 and NFHS-5 in West Bengal, India,” was authored by Tamal Basu Roy, Partha Das and Tanu Das, professors of Geography in Uttar Dinajpur’s Raiganj University, and by Ranjan Roy, a professor of Geography and Applied Geography in the University of North Bengal.

They found that the prevalence of stunting (low height for a child’s weight) increased in Kolkata by 5.4 per cent, in Darjeeling (5.2 per cent), in Maldah (2.7 per cent), Nadia (2.8 per cent), North 24 Parganas (8.6 per cent), South 24 Parganas (9.4 per cent) and Uttar Dinajpur (4.4 per cent).

The number of underweight children increased in Kolkata by a whopping 13.3 per cent, more than in any other district, in Dakshin Dinajpur by 2.1 per cent, in Darjeeling (5.9 per cent), Hooghly (4.7 per cent), Jalpaiguri (0.8 per cent), Nadia (5.8 per cent), North 24 Parganas (5.3 per cent), Paschim Medinipur (0.3 per cent) and South 24 Parganas (4.4 per cent).

“Currently, in West Bengal, 34 per cent of children below 5 years of age are suffering from stunting or acutely undernourished conditions.

Prevalence stunting status among Under 5 children in West Bengal has changed since 2015–2016. As per the state level NFHS report (2019–2020), the proportion of Under 5 children who are stunted increased slightly from 33 per cent to 34 per cent between the last two consecutive NFHS rounds across the state of West Bengal,” the study said, adding that prevalence of underweight and wasted children remained unchanged at 32 percent and 20 per cent respectively.

“The data revealed that there were 13 high priority districts (Darjeeling, Kolkata, Maldha, Nadia, North 24 Pargana, South 24 Pargana, Uttar Dinajpur, Dakshin Dinajpur, Howrah, Hooghly, Jalpaiguri, Bardhaman, Paschim Medinipur) in West Bengal where at least one child growth failure measurement (stunting/wasting/underweight) has marginally or hardly increased in 2019–2020 from 2015 to 2016,” it added.

It requires no rocket science to anticipate the socio-economic background of the under-5 children who may have suffered major growth hindrances at the very beginning of their lives. These numbers of acute malnourishment, derived from the period between 2015-16 and 2019-20, turn dangerous when one adds the Covid-induced lockdown in 2020 and the major humanitarian crisis that has followed thereafter in the last 20 months or so.

Malnourishment in India has always been caused majorly by poverty, inequality and poor health of parents. Massive unemployment, inflation and economic crisis during the pandemic time, one can imagine, may have only forced the children to bear more repercussions.

“As shown in various previous studies low or very less parental educational attainment, poor household living condition, parental un-employment situation, less attention on maternal antenatal & postnatal care, child marriage, mother’s under-nutrition condition, poor maternal and child’s dietary diversity, poor immunization coverage among children are strongly and positively associated with child growth failure incidents,” said the report by professors Tamal Basu Roy, Partha Das, Tanu Das and Ranjan Roy.

However, one thing that could have saved these children from further undernourishment was the Mid Day Meal in Schools (MDMS) scheme.

A school-meal program in government schools, MDMS provides students in primary and upper-primary levels with cooked lunch to enhance their nutritional standards. The scheme was initiated to increase the educational attainment of children, reduce dropout rates and improve their overall growth.

The children who were below the age of five between 2015-16 and 2019-20 have ostensibly grown up now and are expected to be beneficiaries of the MDSM scheme in West Bengal as the state has the best primary education system in India among large states with the highest enrolment rate of 82.7 per cent among boys and 73.3 per cent among girls. But a mismanaged MDMS system is only exacerbating the nutritional crisis among the state’s children.

As per the Union Ministry of Education, a primary student (class 1-5) is entitled to get 100 grams of foodgrains, 20 grams of pulses, 50 grams of vegetables, 5 grams of oil & fat and salt & condiments as needed every day. An upper primary student (class 6-8) should receive 150 grams of foodgrains, 30 grams of pulses, 75 grams of vegetables, 7.5 grams of oil & fat and salt & condiments as needed per day.

The ‘Annual Work Plan & Budget’ of MDMS in West Bengal for the year 2021-22, set the following suggestive menu for students:

Monday: Rice + Dal + Soyabean Curry

Tuesday: Khichadi with leafy vegetables

Wednesday: Rice + Egg curry

Thursday: Rice + Soyabean curry + Dal

Friday: Rice + Dal +Mixed vegetables

Saturday: Rice + Egg curry + Mixed vegetables

“In Kolkata, two eggs are served in a week. Meat, fish or any kind of fruits are served to the MDM takers in some districts like Murshidabad, North24 Parganas and Nadia. The head of the institution and the local people, sometimes, provide additional food items,” added the ‘Annual Work Plan & Budget’ report of MDMS.

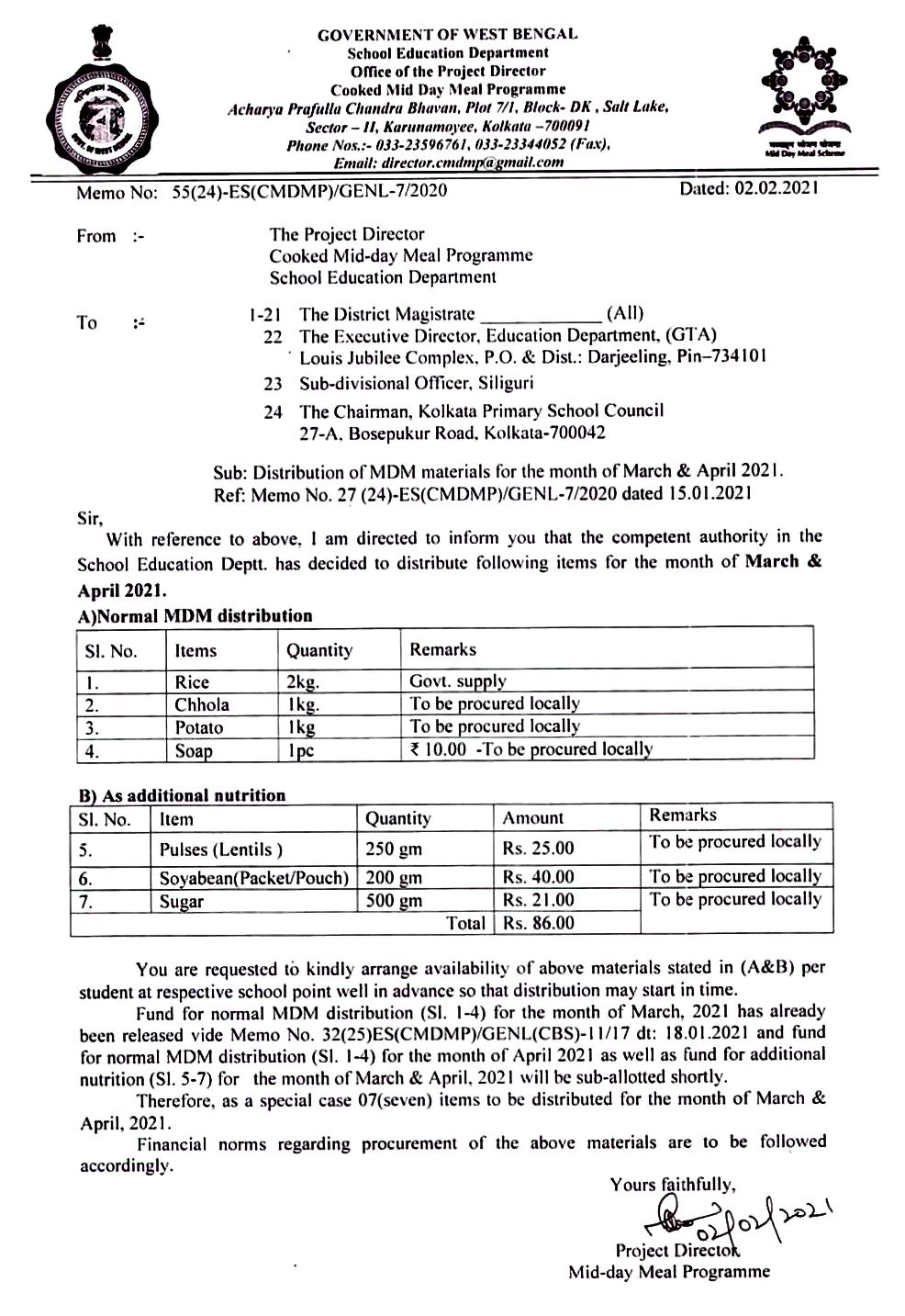

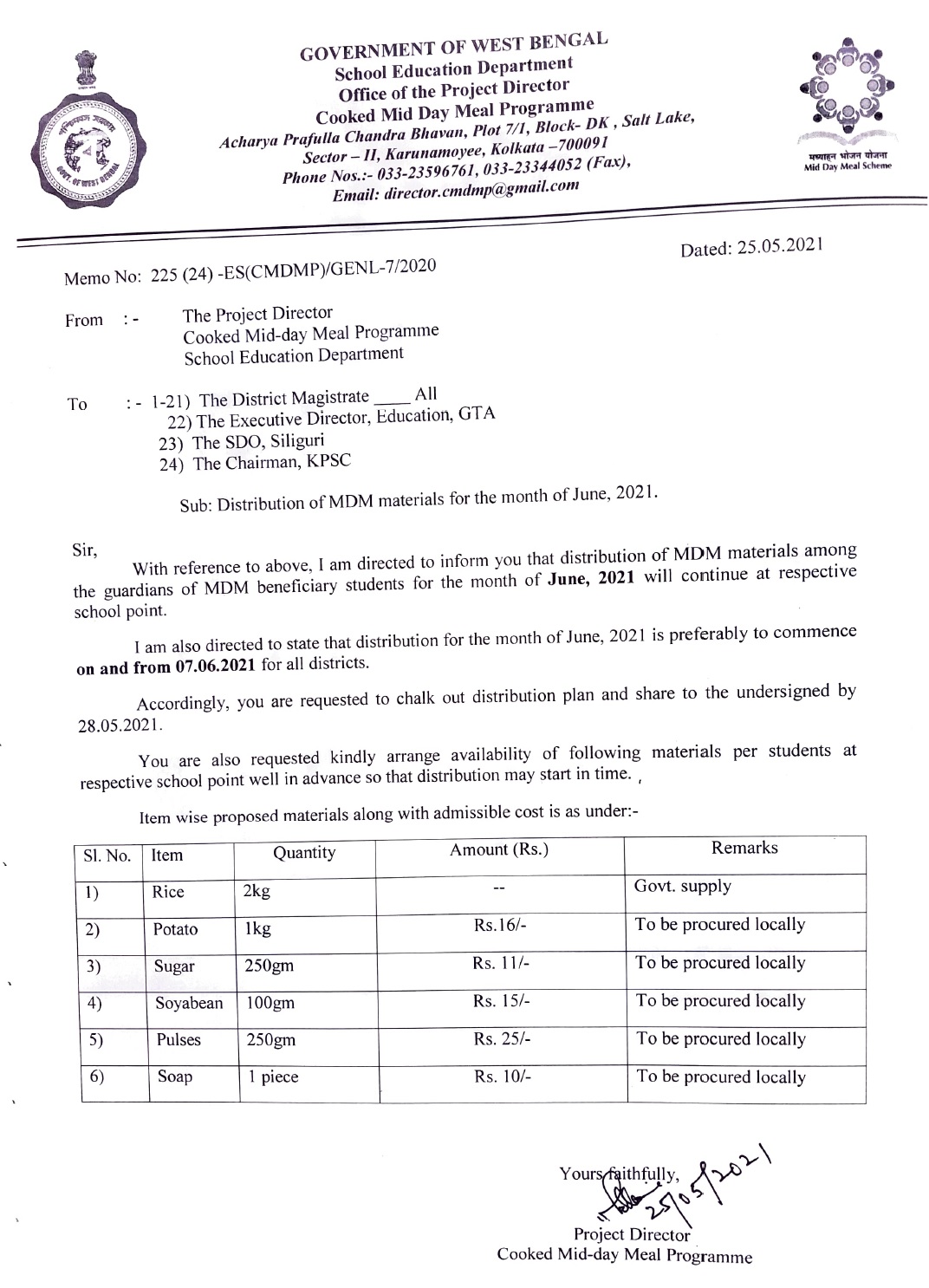

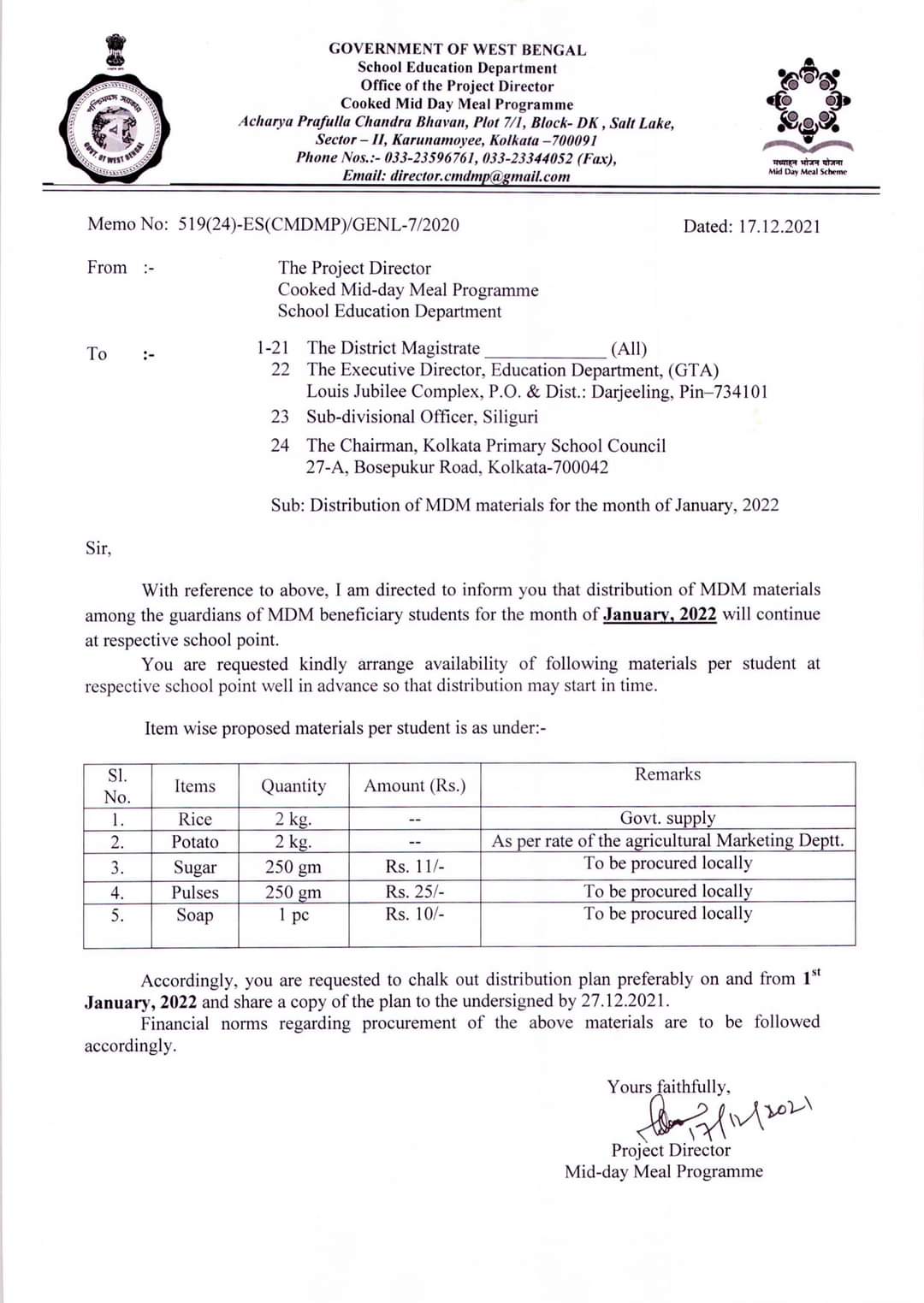

But in its existing form, students in West Bengal have been receiving only 2 kgs of raw rice, 2 kgs raw potato, 250 grams of raw lentils, 250 grams of sugar and a soap every month under the MDMS scheme, said a school teacher on the condition of anonymity. The 49-year-old is responsible for distributing MDMS ingredients at a high school, run by the West Bengal government in the North 24 Parganas district. She further said that the ingredients have remained the same across all classes for the last few months.

According to a report by Bengali daily Anandabazar Patrika, in May last year, students had received soybean and chickpeas along with the other ingredients. In June, one of the items was removed followed by the elimination of another ingredient in September. Since then, students have been receiving only rice, potatoes, lentils, sugar and soap.

“It [the MDMS item distribution] depends on the DM [district magistrate] order. The order mentions what ingredients have to be distributed on what day,” the high school teacher said.

According to the Ministry of Education, Rs 4.97 is allocated for the mid-day meal of a primary student every day, totalling Rs 119.28 for 24 days of schooling in a month. The daily and monthly budget for an upper primary student’s mid-day meal is Rs 7.45 and Rs 178.80 respectively. But since September, the West Bengal government has been spending only around Rs 80 per month for each student’s MDMS ingredients, reported Anandabazar Patrika.

“To increase immunity during the pandemic, a child needs protein. We have been demanding to add eggs in MDMS. We have also said that soybeans cannot be stopped,” Ananda Honda, the West Bengal Board of Primary Education secretary, was quoted as saying in the report.

While there can never be any specific set of answers to why the West Bengal government is not providing students with adequate food items under the MDMS scheme, the Mamata Banerjee-led administration’s lack of will and intent to utilize central government funds in another similar nutrition-related scheme might shed some light.

According to recent data presented before the Parliament by the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD), the TMC-led West Bengal government did not use any funds from the central government under the National Nutrition Mission (Poshan Abhiyaan), launched by the Government of India in its bid to fight undernourishment. Even though there is no evidence to suggest that a similar series of events have taken place in West Bengal with the MDMS scheme, in which the Centre and state share budget in a 60:40 ratio, there have been reports that the central government believes the state does not utilize the funds properly.

Having said that, the BJP-led Centre’s role in ensuring sufficient funds for the MDMS has been dubious as well. Even though the Union Budget for the scheme was raised from Rs 11,000 crore in 2020-21 to Rs 11,500 crore in 2021-22, eminent economist Jean Drèze argued that if inflation was taken into account, funds allocation from the central government had reduced by 32.3 per cent between 2014 and 2021, reported Newsclick.

A flawed and dysfunctional Mid Day Meals in School scheme, especially during the pandemic, can have a long-lasting effect on children of not only this generation but in upcoming generations as well. According to an International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) study, “women who received free meals in primary school have children with improved linear growth”.

Named Intergenerational nutrition benefits of India’s national school feeding program, the study, co-authored by University of Washington’s Suman Chakrabarti and IFPRI’s Samuel Scott, Harold Alderman, Purnima Menon, and Daniel Gilligan, was published in Nature Communications in 2021.

Investments made in school meals in previous decades were associated with improvements in “future child linear growth”, the study said. “Our findings suggest that intervening during the primary school years can make important contributions to reducing future child stunting, particularly given the cumulative exposure that is possible through school feeding programs,” explained Suman Chakrabarti.

The IFPRI study further found that meals in schools do not just contribute to education, but influence students’ “fertility decision” later in their lives and give them access to health care. It cuts down the risk of “undernutrition in the next generation”.

“School feeding programs such as India’s MDM scheme have the potential for stimulating population-level stunting reduction as they are implemented at scale and target multiple underlying determinants of undernutrition in vulnerable groups,” explained study co-author Samuel Scott.

According to the NFHS-5, 21 out of every 100 women of reproductive age are undernourished in West Bengal with a body mass index (BMI) of below 18.5 kg/m. “Undernourished girls have a greater likelihood of becoming undernourished mothers who in turn have a greater chance of giving birth to low birth weight babies, perpetuating an intergenerational cycle,” said a UNICEF report.

Addressing this concern, Harold Alderman, the IFPRI study co-author, said “Findings from previous evaluations of India’s MDM scheme have shown a positive association with beneficiaries’ school attendance, learning achievement, hunger and protein-energy malnutrition, and resilience to health shocks such as drought—all of which may have carryover benefits to children born to mothers who participated in the program.”

Thus, a distorted MDMS scheme, especially at a time when parents of most of the beneficiaries have had to undergo financial fragility, can give Bengal’s children a malnourished future for years to come. To rescue children from the shameful shackles of undernourishment, both central and state governments should keep their political disparity aside and work jointly.

“Various health schemes have been implemented over the last few years by the state and central government to improve child health status; however, there is a need to modify strategies to achieve best health outcomes. Overall development across the state [West Bengal] in subject to socio-economic, political, environmental is required on an urgent basis to improve child health status,” said professors Tamal Basu Roy, Partha Das, Tanu Das and Ranjan Roy’s study.

Niladry Sarkar is a journalist based in West Bengal. He tweets at @niladry17