In the last of the three-part series, we look at how the National Hydro Power Corporation is using all possible measures to ensure that after the recent debacle of the Nyamjang Chhu projects, two of its biggest projects—Tawang 1 and Tawang 2—do not get stuck with clearances and how it is looking to get local support for these projects. However, anti-dam activists are unlikely to make it a cakewalk for NHPC.

Read Part One Here

Read Part Two Here

By Amit Kumar, Twocircles.net

Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh: Mention the name of Tawang to an outsider and the first statement will almost always refer to how beautiful and serene the place is. In the past two decades, the town has increased manifold in size and today boasts of a number of hotels, restaurants along with dozens of local tour operators offering a variety of packages to suit every budget’s needs.

However, as we have seen in part one and part two, these developments have been dwarfed of late by protests against Mega Dams which threaten the district’s ecology and the local people’s office. At the centre of these protests have been the Save Mon Region Federation (SMRF) and its general secretary Lama Lobsang Gyatso, and their main target has been the National Hydropower Corporation (NHPC), which plans to build two massive dams–Tawang 1 and Tawang 2–on the Tawangchu river. These two projects, of 600 MW and 800 MW respectively–will contribute 70% of the 2,200 MW of the scheduled projects in the area now that the Nyamjang Chhu Project has been denied permission by the NGT. No wonder, the central government owned company is going all-out to ensure that these projects are completed on time, so that the benefits of tipping “liquid gold” reach ‘both the state government and the local residents’.

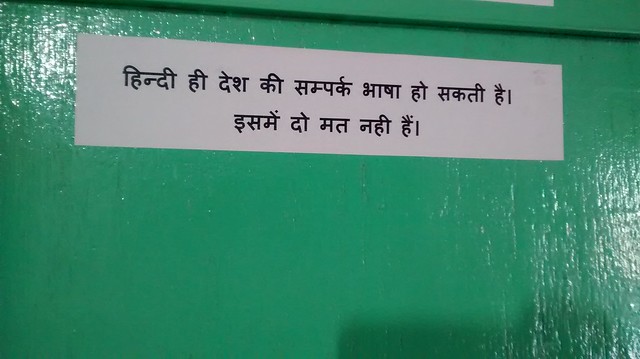

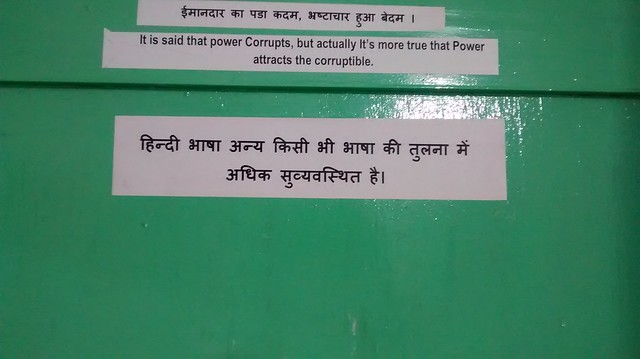

The office of the NHPC, located in the heart of Tawang, is a simple two-storeyed building stacked with hundreds of files in almost all corners. The doors of almost all the rooms have cut-outs stuck on them; telling the visitors about the importance of Hindi in ‘uniting India’. Inside, a senior officer greets me with a smile, before pointing out almost immediately that no part of this conversation could go on record. “I require permission from the central government before being interviewed,” he points out. Off the record, however, he will be happy to share the progress reports and these two projects, and how they plan to convince the locals that the dams are, in his words, “The best sign of progress for Tawang.”

“So many rivers pass through this area. Water is Tawang’s best resource. It is like liquid gold and currently it is being wasted. NHPC wants to help the locals earn a steady income through these projects and the state government in increasing revenue,” he says.

But what about the ecological destruction?

“The impact is being vastly exaggerated,” he says, before adding, “No villages will be submerged.” Here, take a look at this,” he says, presenting a piece of paper which shows how close, or far, the submerged areas are from the village boundaries. Before I can actually see the paper in detail, however, he takes it back. “Plus, remember that the government is paying Rs 65 lakh per hectare to the villagers,” he says. “That is a lot of money for the people here,” he adds. A cumulative impact assessment report of proposed hydel projects in Tawang, prepared by the North Eastern Hill University in 2015 showed that most villages which will come under the impact of Tawang 1 and Tawang 2 have average land holdings of about one acre. So, while there might be enough money for villagers in selling their land, the question remains: how many are willing to sell?

It is important to point out that the NHPC, and the central government, are looking to invest big in the state. Just these two projects-Tawang 1 and Tawang 2-are expected to cost Rs 15,000 crore according to September 2015 prices. However, although the MoUs were signed as early as 2006, the official added that it is unlikely that work would begin anytime soon. More importantly, the projects still need forest and environmental clearance from Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change for different kinds of projects. Also, given that these areas come under the sixth schedule areas, they need consent from the gram sabha which is submitted to the Ministry of Environment while applying for forest clearance. Also, in Scheduled areas where ST population live, Forest Rights under FRA have to be settled before diverting any land to any project, and this is where the most important battle will be fought, according to members of the SMRF.

“If all clearances come through, we can hope of starting by 2017,” said the NHPC official. The scheduled gestation period of Tawang 1 and Tawang 2 stands at 78 months and 84 months respectively, meaning that the projects, if commissioned, will start only after 2023.

The NHPC official added that for Tawang 2, they had received clearance from six out of 13 villages concerned, while for Tawang 1, they had received clearance from two of the 19 villages. However, SMRF said that it was difficult to believe these claims, especially in light of the incident in January, when the monks exposed NHPC of fraudulently getting NOC from two villages for the Tawang 1 project.

The recent win for the SMRF over the Nyamjang Chhu project has given them hope that if they fight well, the upcoming NHPC projects will also not receive clearance from both the central government agencies (NGT) and the local villages. However, NHPC knows this too well: and they are going all-out to counter the claims of SMRF. “These projects will produce enormous job opportunities for the locals and so, we will ensure that all Class 3 and Class 4 labour is sourced locally.

To explain the benefits of the dams, we will distribute audio-visual CDs in every village,” he adds.

The potential job opportunities may well be the biggest offer from the NHPC, because it is unlikely that they will receive positive response over the area that will be submerged along with the loss of thousands of trees, especially when the NHPC official says that to make up for the loss of forest cover, they will plant 10 times more trees.

However, such promises seem hollow, according to SMRF. “Tawang I and Tawang 2 projects, if commissioned, will mean that over 1.5 lakh trees will be cut, almost 60% of them will be trees over 90 cms in girth,” added Gyatso.

Tawang is not an easy place for trees to grow; between October and March, there is hardly any growth due to the cold and snow. “These trees have reached this size because they have been growing for over 40-50 years. Cutting such old trees would mean the death of flora and fauna in this area and only worsen the landslide situation in the district,” says Gyatso. “And where will the new trees grow? There will be hardly any grazing land left after the dams come up. So let alone growing new trees, it will become difficult to even feed the Yaks in the region,” he adds.

In light of the recent shooting on May 2, it will be safe to say that for the first time, the issue has received some sort of national attention. Although NHPC officials we spoke to along with a number of contractors and businessmen in the town say that anti-dam sentiments had nothing to do with the incident and instead blame the differences between Lamas for the death of two people, it is clear that Tawang now faces an uphill task. For NHPC and the central government, the money involved means they will do everything possible to ensure that after lying ten years in a limbo, these projects take off at the earliest. But as the past month has shown, it is unlikely to be a cakewalk.