“Kesari”and “21 Sarfarosh” – a highly fictionalized ode

By Misbahuddin Mirza

Those familiar with America’s Civil Rights movement will tell you that African-American slaves were unofficially divided into two groups – ‘the field negro,’ and ‘the house negro.’ The ‘field negroes’ were slaves that were forced to labor in the fields under harsh conditions; they slept in separate quarters, and longed for freedom from their oppressive slave-masters. The slaves that lived inside the slave master’s house helping with domestic chores, however, did not yearn for freedom – they considered themselves as of higher status then their ‘field negro’ counterparts, and part of their master’s home. During the British colonial rule of India, Indians were similarly divided into two groups – one yeaning for freedom from the brutal colonial occupation; the other serving the colonial masters’, extolling their masters’ virtues, and considering themselves as an extension of the imperial force.

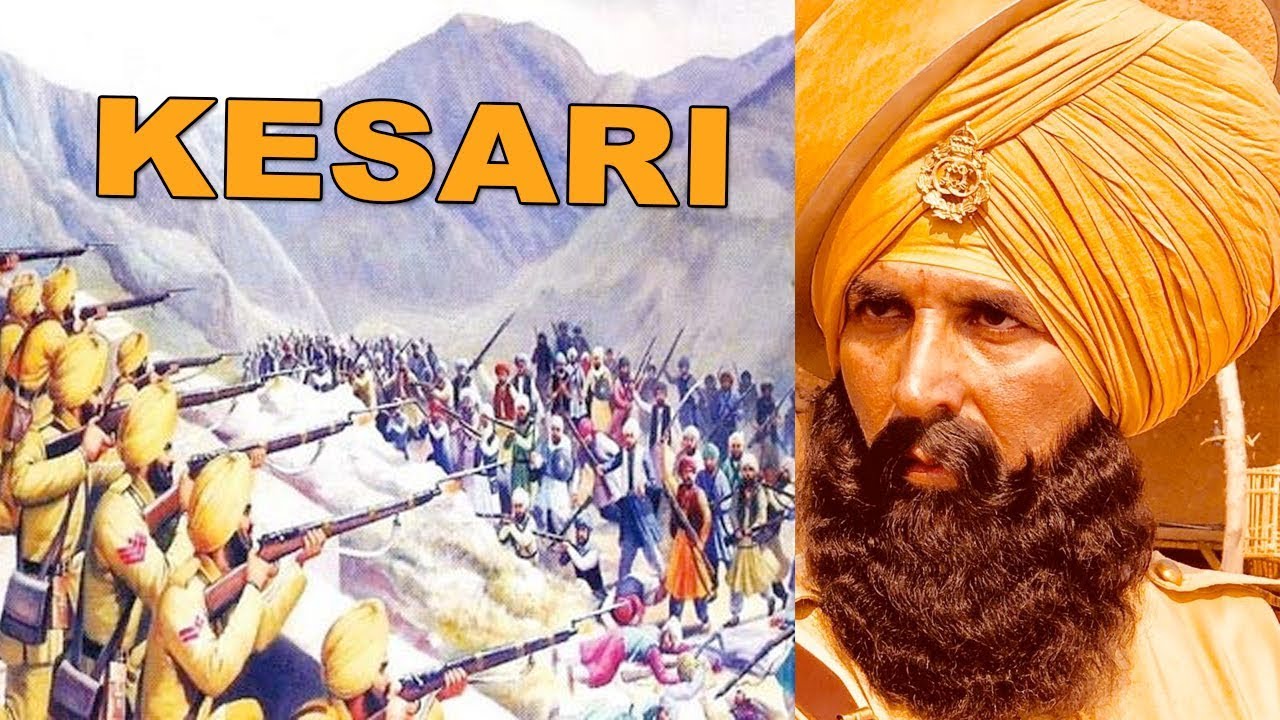

Anurag Singh’s 2019 movie “Kesari” and Raj Acharya’s 2018 TV series “21 Sarfarosh,” are highly fictionalized accounts of the 1897 Battle of Saragarhi, in Kohat district on the Samana Range in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa area along Afghanistan’s border. Saragarhi was a small village communication post between two forts – Gulistan and Lockhart. The battle resulted in a decisive tactical victory for the Emirate of Afghanistan, against the imperial colonial British army. The British colonial force consisted of Sikh soldiers – who were historically used as cannon fodder against the unstoppable Afghans.

India Today’s March 23, 2019 article by Harmeet Shah Singh pointed out the numerous gross historical inaccuracies and blatant exaggerations in the “heavily fictionalizing” movie Kesari. The soldiers building mosques is an absolute lie.

Earlier, about 60 years before the Battle of Saragarhi, during the first Anglo-Afghan war of 1839-1842, the massive British army consisting of British and Sikh soldiers who entered Afghanistan with a lot of pomp and fanfare to constant music, tea, biscuits, caviar, and wine was completely annihilated. Then, again on May 6, 1919, 22 years after the Battle of Saragarhi, the Emirate of Afghanistan invaded British India, yet again decisively defeating the Imperial British army at the third Anglo-Afghan war, and forcing the British to sign the Treaty of Rawalpindi on August 8, 1919, acknowledging Afghanistan as a separate nation.

The vast majority of the British army in India consisted of local Indians – recruited to kill other Indians in order to maintain the brutal occupation of India – “the jewel in the crown.” They also used the same tactics after their defeat during the first Indian war of Independence – using Gurkha, and Sikh armies to retake India.

[caption id="attachment_431024" align="alignnone" width="600"] “The turban would have been the regimental one – in khaki. There would not have been either the scope or the permission to wear kesari, the bright orange colour of the Khals,” Capt Sohal told India Today.[/caption]

“The turban would have been the regimental one – in khaki. There would not have been either the scope or the permission to wear kesari, the bright orange colour of the Khals,” Capt Sohal told India Today.[/caption]

Rabindranath Tagore refused to accept the British title of knighthood, stating that “such mass murderers aren’t worthy of giving any title to anyone.” Shashi Tharoor points out how systematically the British exploited India beyond belief – with examples such as it cost nine times more to lay a mile of railway track in British India, then it did in America of that time.

Stories and movies normally have a point to make. Both the movie ‘Kesari’ and the TV series ’21 Sarfarosh’ leave you wondering about their intended viewpoint. From the disastrous first Anglo-Afghan war, to the first Indian war of independence, the Sikhs, (and the Gurkhas) did loyally serve the imperial colonial British superpower for almost a hundred years. But both the movie and the TV series fail to point out how their colonial British Masters repaid this dedicated service in the form of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of innocent Sikh civilians at the hands of the Gurkha Rifles division of the imperial British army.

[caption id="attachment_431025" align="alignnone" width="759"] TV series 21 Sarfarosh image[/caption]

TV series 21 Sarfarosh image[/caption]

So, what are we celebrating here? Are we supposed to serve our colonial masters, killing our own countrymen for a few silver coins? Is serving and dying to the last man for the British, who Tagore termed as mass murderers, something that needs to be applauded? This movie and TV series remind me of the American fable of the frog who agrees to rescue a drowning scorpion, only to be subsequently fatally stung by the scorpion. It is high time for us to start properly analyzing our thought processes.

Misbahuddin Mirza, M.S., P.E., is a licensed professional engineer, registered in the States of New York and New Jersey. He served as the Regional Quality Control Engineer for the New York State Department of Transportation’s New York City Region. He is the author of the iBook Illustrated Muslim Travel Guide to Jerusalem. He has written for major US and Indian publications.