'False' Narrative, 'Concocted' Stories: A Closer Look at Power Play of Propaganda Films

Devanshi Batra and Syed Ahmad Rufai, TwoCircles.net

New Delhi: As India is witnessing its general elections for the year 2024, the big screen has become a tool to drive political narratives. In recent times, a slew of movies inundating theaters has drawn attention not just for their entertainment value but for their unabashed alignment with political agendas — particularly those of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its ideology of Hindutva.

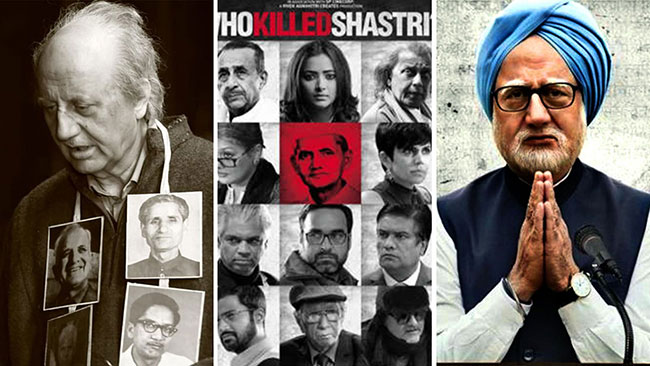

These films — ‘Accident or Conspiracy: Godhra’ and ‘The Sabarmati Report, Aakhir Palaayan Kab Tak?’, ‘The Kashmir Files’, ‘The Kerala Story’, ‘Swatantra Veer Savarkar’, ‘JNU: Jahangir National University’, ‘Mai Atal Hu’, ‘Bastar: The Naxal Story’ — are often thinly veiled propaganda, which serve a dual purpose: bolster the popularity of the incumbents and amplify social divisions through the dissemination of targeted messaging.

The word ‘propaganda’ is a loaded term. Some movies come under the category of propaganda films but others have thinly veiled narratives with indirect messaging.

“There are so many propaganda films, which are based on incidents like airstrikes and attacks carried out by our armed forces. These movies repeatedly show a prime ministerial figure, which its makers want to impose. The idea of a savior prime minister is being reiterated and reinforced among the audience,” NS Abdul Hameed, who is pursuing Ph.D. in visual media culture, told TwoCircles.net.

Quoting a dialogue — “Kisi sarkar ne pehle muh tod jawab nahi diya tha, ab unhe batana padega baap kon hai (no government had given a fitting reply before; now, they will have to reveal who their father is) — from a recently released movie ‘Fighter’, he said this gives out a wrong message that such an action has been carried out for the first time.

“Attack on (Pakistan’s) Balakot was not the first airstrike launched by India, it has happened in the past too. They just want to portray a powerful image of a ruler, and they are using the media for the same,” he added.

According to Anugyan Nag, a professor of film and cultural studies at AJK Mass Communication Research Centre, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, the films being released cater to both categories — unapologetically propagandists and those with undertones of communal partisanship.

At the forefront of this cinematic surge are biopics, glorifying controversial figures associated with the BJP and its affiliated Hindu supremacist groups. People like Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, who is known for his controversial views and advocacy of violence, are being portrayed as larger than life figures, perpetuating narratives that align with the ruling party’s agenda.

These narratives often propagate Islamophobic sentiments and conspiracy theories, further deepening societal fault lines.

While these films may draw inspiration from real-life events, their presentation and treatment transform them into fictionalized and misinformed narratives.

“The entire film industry is not taken over by the ruling dispensation and its allied organizations, but there are some directors who are aligned to the Hindutva ideology,” opined Nag.

He alleged the entrepreneurial businesses, which are said to be affiliated to the ruling party, pump money into the film industry too.

Nag believes that most of these are production houses that produce two or three films, until the public discourse and trends that drive that narrative sustain, and then they disappear.

“Filmmakers who are into production of these types of films will not have long careers,” he added.

In the movie ‘Article 370’, a scene depicting Union Home Minister Amit Shah delivering a speech in the Lok Sabha is a precise recreation of his actual speech in Parliament when Article 370 was abrogated.

Both ‘Accident or Conspiracy: Godhra’ and ‘The Sabarmati Report’ focus only on the 59 karsevaks (religious volunteers) who died in the Sabarmati train burning at Godhra in Gujarat in 2002 and do not emphasize the riots that followed resulting in the death of hundreds of Muslims.

Central to the proliferation of propaganda movies is the concept of narrative control. By monopolizing the cinematic landscape, the ruling party is manipulating public perceptions and shaping collective memory.

Through selective storytelling and narrative framing in these movies, historical events are reimagined to fit a predetermined ideological agenda — whitewashing inconvenient truths and demonizing dissent.

Nag said communal tensions — which are a complex web to represent — have always been a part of mainstream films. “But these were not propagating a certain kind of bias, but now they have a problematic lopsidedness, which vilifies a certain religious community,” he said.

Films on Hindu-Muslim conflict earlier, according to him, used to romanticize both their syncretic histories and narratives that addressed complexities of their divide. But now, he said, it is mostly the vilification of the one community.

The power of propaganda films lies in their ability to shape public opinion and influence electoral outcomes. Through cinematic narratives, the ruling party seeks to control the discourse, presenting itself as the sole protector of national interests while demonizing dissenting voices and Opposition. In doing so, it reinforces its political hegemony and marginalizes Opposition viewpoints.

“Jahan bhi alpsankhyak zyada ho jate hain, bahusankhyakon ko boycott karne lagte hain aur phir shuru hota hai ladai jhagda (wherever minorities reside in large numbers, they start boycotting the majority and then conflict begins),” says a character in the trailer of ‘Aakhir Palaayan Kab Tak?’.

Hameed said the insidious nature of propaganda films lies in their subtlety. Unlike overt forms of propaganda, which are easily recognizable and thus subject to scrutiny, these films operate on a subconscious level, seeping into the collective consciousness and shaping perceptions without arousing suspicion.

By embedding ideological messaging within seemingly innocuous narratives, they normalize and perpetuate divisive rhetoric, exacerbating societal tensions and eroding trust in democratic institutions.

Furthermore, he said, the commercial success of propaganda films incentivizes their continued production, creating a feedback loop where partisan narratives are amplified for electoral gain.

As audiences flock to theaters in search of entertainment, said Hameed, they unwittingly become conduits for political indoctrination, unknowingly contributing to the proliferation of propaganda.

“The targeted audience of such movies is a particular strata of population and demographics. For instance, the ‘Kerala Story’ was not received well in Kerala. The southern state rejected this film but at the same time, north Indians praised it. By weaving false narratives, these films aim to polarize society. Through false numbers and manipulated data and information, these films feed narratives to the target audience,” said Hameed.

Cinema as a form of political mobilization

The nexus between these propaganda films and the ruling political establishment is now more obvious than ever. Reports also indicate close ties between the filmmakers and the BJP, with instances of tax waivers and government-sponsored screenings to ensure wider dissemination of these narratives.

The prime minister himself has publicly lauded certain films, providing them with a veneer of legitimacy despite accusations of factual inaccuracies.

“There is continued support, appreciation and encouragement from the government and state players to these propaganda films. The prime minister during an election rally in Karnataka praised ‘The Kerala Story’. When ‘The Kashmir Files’ was released, even Cabinet ministers rushed to theaters to watch it. These films are getting immense support on the theatrical release only because it helps polarize the society on religious lines,” said Hameed.

For instance, ‘Article 370’ celebrates Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to revoke the special status of Kashmir, painting him as a decisive leader safeguarding India’s interests. However, critics have denounced the film for its distortion of facts and perpetuation of divisive rhetoric.

Similarly, films propagating Islamophobic stereotypes and conspiracy theories about conversions and ‘Love Jihad’ serve to fuel communal tensions and undermine social cohesion.

Is the line between entertainment and political campaigning now blurred? The disclaimer of most of these films say all events, characters and incidents are fictionalized for dramatization or loosely based on true events. However, by mixing fact with fiction, they not only distort historical truths but also manipulate public sentiments. From the ‘Kashmir Files’ to the ‘The Kerala Story’, a number of movies stand witness to this.

According to the filmmakers of ‘The Kerala Story', the movie “unearths” the events behind “approximately 32,000 women” going missing in the southern state. However, critics see this as “exaggeration” and “distortion” of numbers. The director also later said that 32,000 was an arbitrary number.

“These movies serve as powerful tools for political parties to disseminate their message, particularly during election campaigns when public attention is at its peak. In the run-up to the 2024 elections, the BJP has intensified its efforts to propagate messages through various means, including movies. Their release prior to the election and the party’s unapologetic support to them serve to magnify Modi’s political agenda and his image as a leader,” said Hameed.

He pointed out that while these films do not explicitly dictate voting choices, it crafts a narrative that unmistakably delineates between protagonists and antagonists, subtly influencing audience perceptions.

Through carefully crafted storytelling, visuals and rhetoric, he said, these films seek to portray the party in a favourable light while vilifying its opponents.