Swastika Verma, TwoCircles.net

“Let’s die, let’s die here,

We aren’t born only to die…”

— Untouchable Spring, G. Kalyana Rao

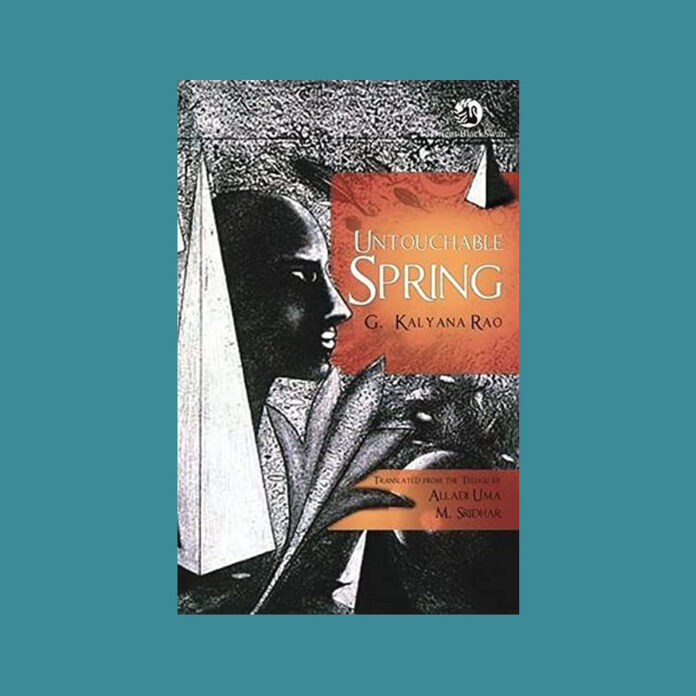

In the fertile yet fractured rural landscape of Tamil Nadu, G. Kalyan Rao imagines a village called Yennela Dinni – a place where the Mala and the Madigas live under the shadow of relentless caste discrimination. Through his 2010 Telugu novel ‘Antrani Vasantam’ (translated into English as ‘Untouchable Spring’ by Alladi Uma and M. Sridhar), he crafts one of the most heartbreaking literary accounts of Dalit oppression and their resistance through art, memory and education.

At the centre of this novel is Ruth, the narrator and chronicler of seven generations of trauma. Bound to the Mala and Madiga community through her marriage to Reuben, she carries the haunting legacy of caste violence. Her voice channels the sorrow, strength and resilience of Reuben’s people whose voices were long silenced and stomped upon by the upper castes.

Set in Yennela Dinni, a small village inhabited by the untouchables (the Malas and the Madigas) and their upper-caste overlords (the Reddys and the Chaudhrys), ‘Untouchable Spring’ tells the story of a family’s journey from the motherhood of Boodevi to the courage of Subhadra, Yellena’s wife and Siviah’s mother, who becomes a turning point for the community’s conversion to Christianity and pursuit of education.

Rao’s writing is visceral and fusing the earthy romance of nature with the Mala-Madiga community’s intimate connection to the land. Ruth becomes the vessel of collective memory, preserving the intergenerational pain of Dalit lives crushed under Brahminical dogma and Manusmriti’s decree. Reuben’s voice in the novel highlights an anger at the Vedic justification of caste.

“The story of my birth and your birth, where did that come from? From a curse… Who is that half-man who drew the line on Yellena’s forehead and his life? Who is that half-animal? It is in the shape of paper. The term ‘smriti’ appears in his name… the half-animal is Manu. The distorted Manu.”

Family and art emerge as vital tools of resistance. Yellena’s trauma – his naked flight to another village, his discovery of dance and song to cope – becomes a symbol of reclaiming identity in a world that devalues Dalit bodies and stories.

The novel treats memory as both wound and weapon. Subhadra’s act of digging a water stream for her people, seen by villagers as divine possession, is a moment of radical defiance, a memory that must be passed down like an heirloom of courage.

Rao does not allow these acts to fade. He ties together Yellena’s songs, Reuben’s diaries, Ruth’s poems and her closing memoir as a family’s collective resistance, a way to document, preserve and honour the brutal but inspiring legacy of survival.

Ruth says of Reuben, “He laughed as he narrated. Cried as he narrated. His eyes sparked then. His eyes got wet then. She hid that sparkle in her eyes… In truth, they are not just the memories he shared. Wet eyes wrench the heart. Touch the spinal cord. They haunt.”

These memories surface again and again in moments that demand remembrance. Siviah’s starvation during drought-induced migration, Subhadra’s refusal to be silent and even the coconut saplings he buried in desperation, all function as symbols of defiance and dignity. They are not just memories but landmarks in a landscape of resistance.

The metaphor of the spring is layered and powerful. The title ‘Untouchable Spring’ refers not just to water, but to the untouchable memories of the Dalit struggle, memories that nourish and revive even when caste society tries to bury them. Rao uses the spring as a symbol of continuity, hope and life itself, something the Dalit community has always had to fight for.

The novel opens and closes with the Yennela Pitta, the bird whose call Reuben tries to mimic for Ruth. This motif of nature, the cyclic flow of time and the rebirth of memory highlights the idea that the Dalit struggle, like the birdcall or spring, cannot be extinguished. It will echo until justice is realised.

For Ruth, writing becomes both mourning and memorial. After losing Reuben and their child, she continues the legacy of witness. The women in the family, like Ruth and Subhadra, are often the quiet but forceful carriers of remembrance – which is alert, observant and essential to the cause their sons and husbands champion.

The spring in ‘Untouchable Spring’ is at once literal and symbolic, a stream of water, of memory and of rebellion. It flows with the sorrow and strength of a community whose pain has been ignored, but never erased. Rao’s use of the term “untouchable” carries a dual force – it names the community the story is about and it reclaims their identity as indomitable, sacred and unerasable.

In this novel, memory becomes the fiercest form of resistance. Rao ensures that the suffering, the songs and the courage of the Malas and Madigas are not merely archived but honoured. The spring flows not only with water, but with stories that will not dry out.

Rao once mentioned plans to write a sequel. Whether it was ever completed is unknown. Perhaps, like the dream of caste abolition, it remains unfinished but never abandoned. Just like the untouchable spring.