Unzila Sheikh, TwoCircles.net

New Delhi: Anil Singh, 30, was born in Bhoomiheen Camp, a settlement in southeast Delhi, now bulldozed, where his parents, migrants from Bihar, had lived since 1984. On June 11 this year, Singh, his wife and their two daughters stood by as JCB excavator flattened their jhuggi during a demolition drive. Days later, Singh says, another blow followed. The Election Commission struck his name off Delhi’s voter list.

“The EC removed my name citing that my house number was zero. Local political members had added my name to the Bihar voter list in 2017. I never voted there. I did not even know that my name was added in the electoral roll there. I have been on the Delhi voter list since 2008. My name was removed following the SIR (Special Intensive Revision) in Bihar because I was a migrant, and now from the Delhi list because of my address,” he said.

The name of five other members of his family – his wife, two brothers and their wives – have also been removed from the electoral roll.

The demolition itself happened swiftly. “A court judgment came on June 6. We received the notice on June 8. And by the morning of June 11, seven to eight bulldozers arrived at around 5:30 a.m. and started tearing everything down,” he said.

The demolition at Bhoomiheen Camp was carried out under heavy police deployment. Senior AAP leader Atishi, MLA from Kalkaji, criticised Delhi Chief Minister Rekha Gupta for breaking her promise.

“BJP’s bulldozer started running in the Bhoomiheen camp from 5 a.m. Rekha Gupta, you said three days ago that not even a single slum would be demolished, then why are bulldozers running in Bhoomiheen Camp?” she asked the chief minister in a post on X (formerly Twitter).

Singh estimated that between 600 and 700 families lost their homes that day.

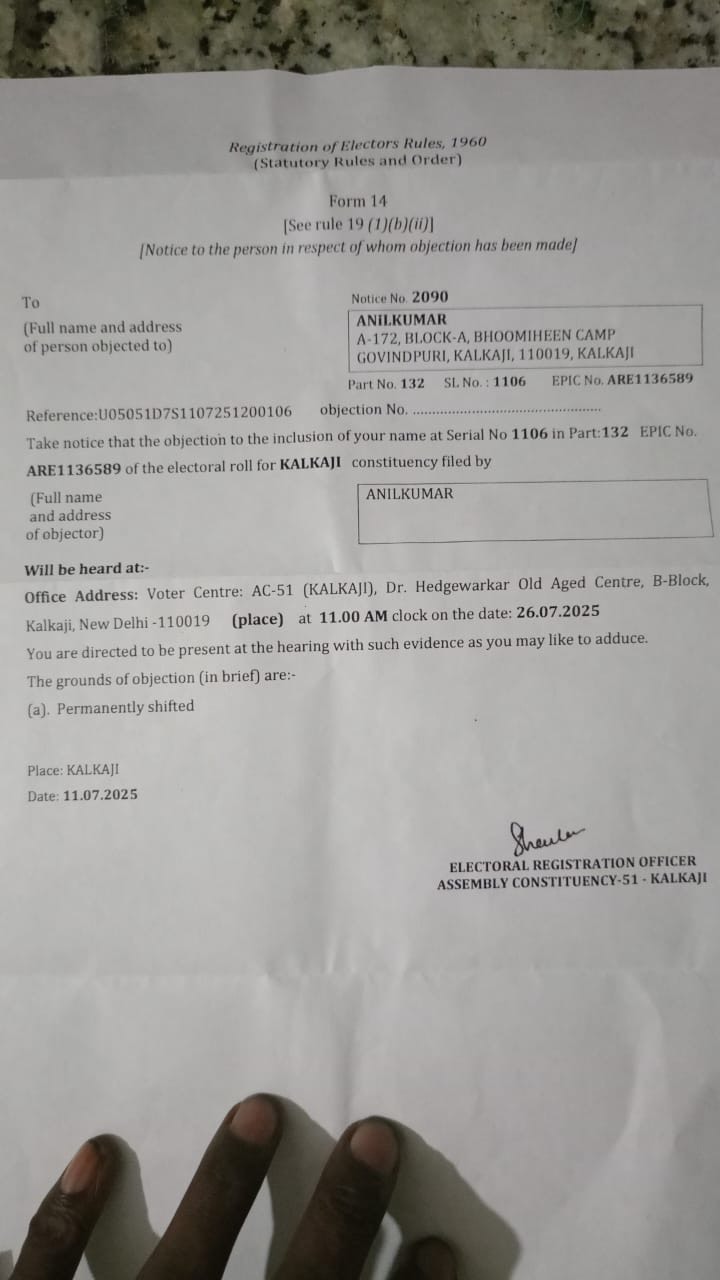

His troubles continued. “We received the ECI notice on July 26, the same day a hearing was also scheduled. They asked us to produce the electricity bill for July to confirm our address. But how could we provide a bill when our homes had already been demolished in June?” he said.

CM Gupta defended the bulldozed action, stating on June 8 that authorities were obligated to carry out demolition orders issued by the court. She also emphasised that displaced families had been provided with alternative accommodation.

Largely inhabited by migrant workers, the Bhoomiheen Camp has faced three separate demolition drives in over a year. Officials from the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) have said the demolitions were necessary to address flooding problems caused by narrowed drains.

Hari Shankar, another resident whose name was removed from the Delhi’s electoral rolls, rejected the ECI’s claim that he had permanently shifted.

“I never left that place. I still live on the same spot, on the rubble, in a temporary shelter. I meet the legal condition of ‘ordinary residence’ under election law,” he said.

He shared his experience at the office of the Assistant Electoral Registration Officer (AERO).

“I went there on July 19, but it was closed. On July 21, I met the AERO, Ms. Anju Gupta, and submitted my reply. Shockingly, she refused to accept it without giving any reason. This violates the rules and my right to be heard. Deleting my name is illegal as the law clearly states that even people without permanent homes, including homeless or displaced persons, have the right to vote,” he said.

He pointed out that courts and the ECI have repeatedly held that residents of jhuggis (makeshift or informal dwellings) or unauthorised colonies cannot be removed from electoral rolls solely due to their housing conditions.

“I want the wrongful deletions to stop. I am still living at the same location; and therefore, keep me on the roll,” he said.

Shankar filed a complaint on July 24. The Electoral Registration Officer’s response stated, “Hari has acknowledged that his house in Bhoomiheen Camp was recently demolished by the DDA. He has not left the premises and continues to live at the same location or in its immediate vicinity. Thus, he has ceased to be ordinarily resident of Bhoomiheen Camp, and his name has been deleted from the electoral roll after following due procedure/guidelines.”

Pavan Kumar Maurya, 37, also born in Bhoomiheen Camp, now lives on the footpath across from the demolished settlement with his wife and three children. His name too, he said, was deleted due to address-related reasons.

Bhoomiheen’s story is far from isolated. According to a report by the Housing and Land Rights Network, Delhi saw 78 eviction drives in 2022-23 alone, resulting in the displacement of nearly 3 lakh people.

Human rights lawyer Kawalpreet Kaur alleged many of those displaced find themselves excluded from government housing programmes.

“In 2015, the Narendra Modi government introduced the ‘Housing for All by 2024’ mission under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (Urban). About 29,976 units were built in Delhi between 2019 and 2024. But eligibility for this scheme is linked to clear land titles or having lived in a permanent house. Many evictees, despite having water bills, electricity bills and voter ID cards, do not qualify,” she said.

She added that a legal tug-of-war continues over housing allocation. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs wants to rent out units under the Affordable Rental Housing Complex scheme, while the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board advocates for using them for resettlement.

Many earlier-constructed units under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission remain unfit for habitation.

“Temporary shelters do not count as permanent resettlement. Governments have rarely been held accountable for failing to provide adequate housing,” Kaur said.

The law around voter eligibility is clear. Section 22 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950, allows electoral officers to remove names from rolls if the person is no longer an “ordinary resident”. However, due process and a fair hearing are mandatory.

Rule 21A of the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960, requires field verification and public notice before any deletion.

The ECI’s own registration manual acknowledges the rights of homeless citizens. It explicitly states that no documentary proof of residence is required and that booth-level officers must verify whether a person spends nights at the claimed location.

For residents of Bhoomiheen Camp, the experience is both legal and personal. First, bulldozers erased their homes. Now, many say they are being stripped of one of their most fundamental rights.