Sanjana Chawla, TwoCircles.net

New Delhi: The global fashion industry has long been under scrutiny for its recurring pattern of cultural appropriation, particularly when it comes to India’s rich heritage. A recent controversy involving luxury brand Prada and its “leather flat sandals”, which are strikingly similar to India’s Kolhapuri chappals, has led to a debate, exposing the deeper issues of Western exoticism and its damaging impact on Indian artisans and their traditional crafts.

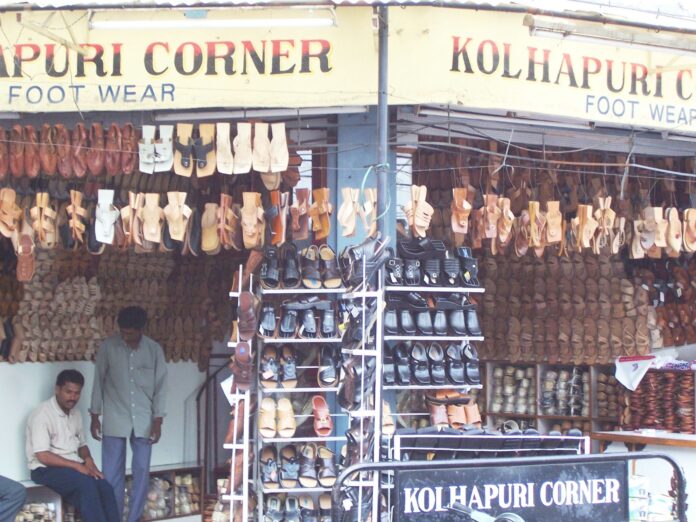

Priced at over Rs 1 lakh, Prada showcased its “leather flat sandals” at Milan Fashion Week in June 2025. For many in India, the design was instantly recognisable as the Kolhapuri chappal, a handcrafted footwear tradition that dates back to the 12th century in Maharashtra and Karnataka.

The brand’s initial failure to acknowledge the design’s Indian origins sparked outrage on social media, with critics accusing Prada of “cultural theft” and “blatant design theft”. Under mounting public pressure, the Italian fashion house’s CSR chief Lorenzo Bertelli admitted the sandals were “inspired by traditional Indian footwear” and expressed willingness to engage with local artisans.

But this was far from an isolated case.

Earlier this year, Prada was also accused of copying Punjabi juttis under the label of “antiqued leather pumps”. The pattern (copy, get caught, apologise and acknowledge) reveals how brands often exploit the exotic appeal for profit, addressing ethical concerns only after social media backlash.

Zeeshan Akhtar, co-founder of Zero Tolerance, calls cultural appropriation a “theft with good PR”. “You take something sacred or meaningful from a community, slap it on a product, make money and act like you manufactured or designed it. The line? Simple: did you ask? Did you pay? Did you credit? If it is all ‘no’, you are appropriating,” he explains.

He recalls seeing a luxury brand selling “tribal jewellery” identical to his grandmother’s and marketing it as “bohemian chic”. “That is not appreciation. That is erasure with a markup,” he stresses.

The Exotic Gaze

Non-Western cultures are often reduced to spectacle, used as props rather than living heritage. Zeeshan describes this “exotic gaze” as “exhausting”. He says, “India becomes this Instagram filter, full of elephants, spices and mystical vibes. But where is the techie in Bangalore? The artist in Mumbai? The startup founder dealing with funding issues? We are not your aesthetic. We are people.”

The film ‘Sex and the City 2’ serves as an example. Fashion critics and Instagram pages like ‘Diet Sabya’ pointed out repeated mislabelling of lehengas as saris, despite the show’s focus on fashion and the involvement of an Indian writer and actor. The film also drew criticism for its orientalist portrayal of Middle Eastern men and women, reinforcing stereotypes and ignorance rather than respect.

When cultures are repeatedly flattened into costumes or clichés, audiences become desensitised to their true depth and history. This conditioning paves the way for luxury brands to extract elements, rebrand them and sell them at staggering prices without meaningful scrutiny.

From colonial photography to Bollywood, Zeeshan believes, historical portrayals, have cemented this perception, reducing India to a “theme park” in the popular imagination. He laments that “the quiet moments such as a chai (tea) conversation, a child doing homework or normal Tuesday stuff never made it to the movies”.

The Unseen Toll on Artisans

When global brands mass-produce and rebrand traditional Indian designs, they strip them of context and meaning, devaluing centuries-old craftsmanship. Artisans often spend weeks or months on a single piece, working under precarious conditions with little pay and no intellectual property protection.

Pankaj Kumar, an Usta artist from Jodhpur, finds it “disheartening when global brands borrow from our traditions without any acknowledgment”. He stresses, “Appreciation becomes appropriation when credit and context are missing. Such incidents dilute the original narrative and value of our crafts. While they may bring momentary visibility, they rarely translate into sustained demand or benefit for grassroots artisans.”

What gets lost? “The soul,” Zeeshan explains, stating, “A real Kolhapuri chappal has the artisan’s fingerprints on it, literally. Each pair is slightly different because humans are not machines. When a brand like Prada, Gucci or YSL makes their version, it is perfect, sterile and soulless. They are selling the look, not the story. It is like buying a photocopy of a love letter, technically the same words, but completely hollow.”

Prakash Damle, a Kolhapuri seller from Maharashtra, says with concern, “Today’s generation and foreigners see our chappals as a fashion trend. They think it is cool. But not for us. We see our family’s history and our children’s future in these chappals. When a big brand copies our design, they bruise our livelihood.”

At his stall in INA’s Dilli Haat, he points out the difference, “A Kolhapuri chappal takes days of careful work that involves cutting, stitching, braiding and tanning. The leather is treated a certain way. The luxury versions are made in minutes by a machine. The difference is the soul, the love with which it is handmade, not machine-made.”

This commodification places branding above craftsmanship. Still, artisans like Kumar hold on to their pride. He explains, “Fragments of mural art and Usta art often appear in commercial products without context or depth. What is copied is style; what remains untouched is the soul and storytelling.”

He highlights how artisans are struggling with limited exposure, changing consumer trends and the rise of minimalism that sideline intricate crafts.

As economic pressures mount, younger generations see little value in learning labour-intensive techniques that cannot guarantee livelihoods. This threatens the survival of cultural practices honed over centuries.

Prakash asks with anguish, “My father taught me, and his father taught him. We are links in a chain. But how can I tell my son to learn this craft when big companies steal our designs and sell them for a fortune, while we struggle to survive?”

Many artisans are now forced to leave their crafts behind, migrating to cities for low-skilled work. This is not only an economic loss, it erodes cultural memory, storytelling and identity.

However, social media has changed the dynamics. Zeeshan adds, “Appropriation is ancient, but now there are receipts. Before, an artisan might never know their design was stolen. Now they see it on Instagram within hours. The game has not changed, but the scoreboard is visible.”

Partnership, Protection and Respect

Ethical engagement requires more than acknowledgment. It demands genuine collaboration, equitable sharing of benefits and respect for cultural integrity. When done right, such partnerships preserve heritage and provide sustainable livelihoods.

Dior’s Autumn/Winter 2023 collection highlighted 25 Indian embroidery techniques, working directly with ateliers such as Chanakya School of Craft. This ensured artisans were fairly paid, recognised and empowered to pass down techniques.

Similarly, Christian Louboutin partnered with Chennai-based atelier Vastrakala for embroidery in luxury footwear, committing to authentic incorporation.

Such collaborations prove profit and respect can coexist. “The responsibility of luxury brands must be clear. Some brands collaborate genuinely, others just raid the cultural closet and ghost the creators. If you are inspired by someone’s heritage, pay them. It is that simple. Do not just take and run. Build relationships, share profits and give credit publicly,” Zeeshan insists.

Kumar envisions a future rooted in co-creation with dignity. “Transparent credit, fair reimbursement and cultural integrity must be the cornerstones of ethical partnerships. Artisans should be seen not just as suppliers but as storytellers,” he says.

Strengthening the Threads

India has taken steps to protect traditional knowledge through legislation like the Geographical Indications (GI) of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999. Kolhapuri chappals, for instance, received GI tag in 2019. Even so, enforcement remains weak, and imitations continue to flood the market.

Zeeshan describes protections as a “patchwork”. “The Copyright Act is for individuals, not communities. WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organisation) frameworks are slow. Most systems were built for Western ideas of ownership. GI tags are like having a fancy certificate no one respects,” he highlights and adds enforcement is minimal, and many artisans do not even understand how the system works.

Kumar calls for fundamental change: “We need education for artisans and audiences, along with skill transmission, fair platforms and design innovations. Empower artisans with knowledge and direct market access.”

He advocates systemic overhaul: a Cultural Heritage Protection Authority, mandatory ethical sourcing certifications and Community IP Trusts to hold collective rights. He also suggests reversing the burden of proof to force brands to prove originality in appropriation cases.

Fashion must evolve beyond consumption to embody culture, respect and reciprocity. Preserving India’s living heritage is a shared responsibility of brands, governments, consumers and global institutions. Only then can artisans continue to carry forward traditions with dignity and ensure the soul of their craft endures.