Shahzeen Khan, TwoCircles.net

Patna: On a muggy September evening, Kako market in Bihar’s Jehanabad district came alive at dusk. The bargaining voices of women cut through the sputter of two-wheelers inching past, while hawkers arranged neat rows of brinjals, cucumbers and green chilies under the dim glow of hanging bulbs.

For nearly four decades, one corner of this market belonged to Mohammad Mohsin, a 70-year-old vegetable seller from Pakhanpura village. His earnings rarely exceeded Rs 300 a day, which was never much, but “enough” to raise three sons and five daughters and keep his modest household afloat.

On the night of September 17, the septuagenarian was beaten to death for allegedly refusing to pay a market “fee” of just Rs 5 to men who “routinely extorted” vendors in the area.

“They came for money every day, sometimes Rs 10, sometimes Rs 5,” said Rukhsana Khatoon, his sister-in-law.

That evening, Mohsin was allegedly asked by the unauthorised toll collector to pay Rs 20. He said he could give Rs 15 right then and promised to pay the remaining Rs 5 later, explaining that sales had been slow. The collector, who was later identified as Vicky Patel, reportedly began verbally abusing and threatened him that he would not be allowed to set up his stall unless the full amount was handed over.

“He even threatened my brother’s life before attacking him,” said Rukhsana. According to her, the collector told Mohsin, ‘I will not hesitate to go to jail for killing you, but I won’t let you set up your stall without paying full amount.’

Crowd Watched in Silence

A shopkeeper who watched the incident from across the street said, “It is not that people did not see. They chose not to get involved.” Fear, he explained, is common in the market in such situations. “If you speak up, you will be the next one. Everyone knows how things work here.”

Both Mohsin and Rukhsana had been selling vegetables in Kako market for years. On the day of the attack, Patel visited their stall twice, first to allegedly threaten and later “to carry out the fatal assault”.

Rukhsana, who witnessed the attack and later lodged a police complaint, struggles to understand how people who had bought from Mohsin for decades could walk past his unresponsive body. “They knew him. He sold them vegetables every day. But when he was being brutally thrashed, no one stood by him,” she described the horror.

She recalled Patel allegedly striking Mohsin first in the groin, then bringing down a heavy iron weight used for measuring vegetables onto his chest and head. “It happened in seconds. He collapsed instantly,” Rukhsana said. People continued shopping and stepping past him as if he were not there.

Vendors too admitted that they saw the assault but did not intervene. Some cited fear of Patel’s political connections, while others spoke of a culture of resignation, where disputes involving contractors are considered too risky to confront. Several of them alleged that Patel’s aggression was widely known.

“He would shout, push and sometimes slap people. But no one expected he would kill,” said a fruit seller.

Locals also alleged Patel often flaunted his political connections on social media. Once seen at ruling Janata Dal (United) or JD(U) rallies, he now appears in the Opposition Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) circles. “He knew he could act with impunity,” said a vendor.

Unregulated Market System

Vendors at Kako whisper about daily harassment but hesitate to speak openly, fearing reprisals. “Everyone knows how it works. But people keep their heads down. If Mohsin had not resisted that evening, perhaps he would still be alive. That is the truth nobody will say aloud,” said a shopkeeper.

These collections have long replaced the regulated Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) mandi system that Bihar dismantled nearly two decades ago. With no state-managed structure for trade, vendors now pay these informal tolls. “You pay if you want to sit. We all know it is illegal but resisting means trouble. Mohsin resisted,” said a vegetable seller.

In Kako, the killing is remembered less as an isolated crime and more as the latest expression of an everyday arrangement, where local vendors and traders are allegedly compelled to pay petty sums to informal ‘collectors’.

“The system itself is broken. The regulated mandi system was scrapped in Bihar in 2006 when Nitish Kumar took over as the chief minister. Since then, ‘fees’ are extorted, mostly by contractors with political links. Vendors like Mohsin, who used to earn Rs 200 or Rs 300 a day, are the ones who pay the price,” said a local journalist.

“The system is simple,” he explained, “The municipality outsources collection to a contractor. The contractor hires strongmen. Those strongmen extort the poorest sellers, while everyone ‘above’ them takes a cut.”

Police Action

The police registered a case of culpable homicide on the same night (September 17) under Section 103(1) of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, and promised to arrest the accused. Authorities also announced Rs 2 lakh in compensation to Mohsin’s family, a promise that remains unfulfilled so far.

Following a complaint lodged by a member of the legislative council (MLC) on September 23, the accused has now surrendered.

Reacting to the incident, political activist Muzammil Imam wrote on social media, “What kind of society are we, where a man lies dead in front of you, and people continue to shop.”

“Money is not justice. This is a broad daylight murder, not an accident. If society stays silent now, tomorrow it will be our turn,” he cautioned.

‘How Can a Person Be Killed for Rs 5?’

Jameela Khatoon, Mohsin’s wife, fainted the moment she heard the news of her husband’s murder. Neighbours rushed her to the hospital. Already battling filaria, she had leaned on her husband for daily care. Now, grief has hollowed her voice so completely that she can barely speak.

For neighbours in Pakhanpura village, the loss cuts deep. “He was a man who never raised his voice and never fought with anyone. To think his life ended like this, over Rs 5, is unimaginable,” said one resident.

Another added, “She has not stopped crying. She keeps asking the same question again and again: how can someone kill her husband for Rs 5?”

Mohsin is remembered here as gentle, soft-spoken and almost self-effacing. “If someone could not pay, he would still give them vegetables,” said a villager, shaking his head.

His three sons sat in stunned silence, with eyes fixed on the courtyard where their father’s body had lain on a cot before the final journey. “He worked very hard every day. He never argued and never cheated anyone,” said Mohammad Guddu, the eldest among the three.

“We do not want money. We want the truth. We want to know why my father had to die for Rs 5. There was no one to speak for us. We were left alone,” said the daily wages labourer, with his voice trembling.

Kako is a Hindu-majority town, with Muslims making up only around 10 percent of the population. In Pakhanpura village, Mohsin’s family and one of his brothers are the only Muslim households. The family, however, says there has been no communal angle to the incident.

Outrage, But Will There Be Accountability?

That night, Mohsin’s family and supporters blocked NH-33 outside Kako police station for nearly four hours, demanding Patel’s arrest and an end to the illegal toll-collection system. The police promised swift action with the monetary compensation and urged the crowd to disperse so the body could be sent for post-mortem.

Officials later said if the mandi had been auctioned, steps would be taken for its cancellation, as Bihar currently has no organised mandi system in place.

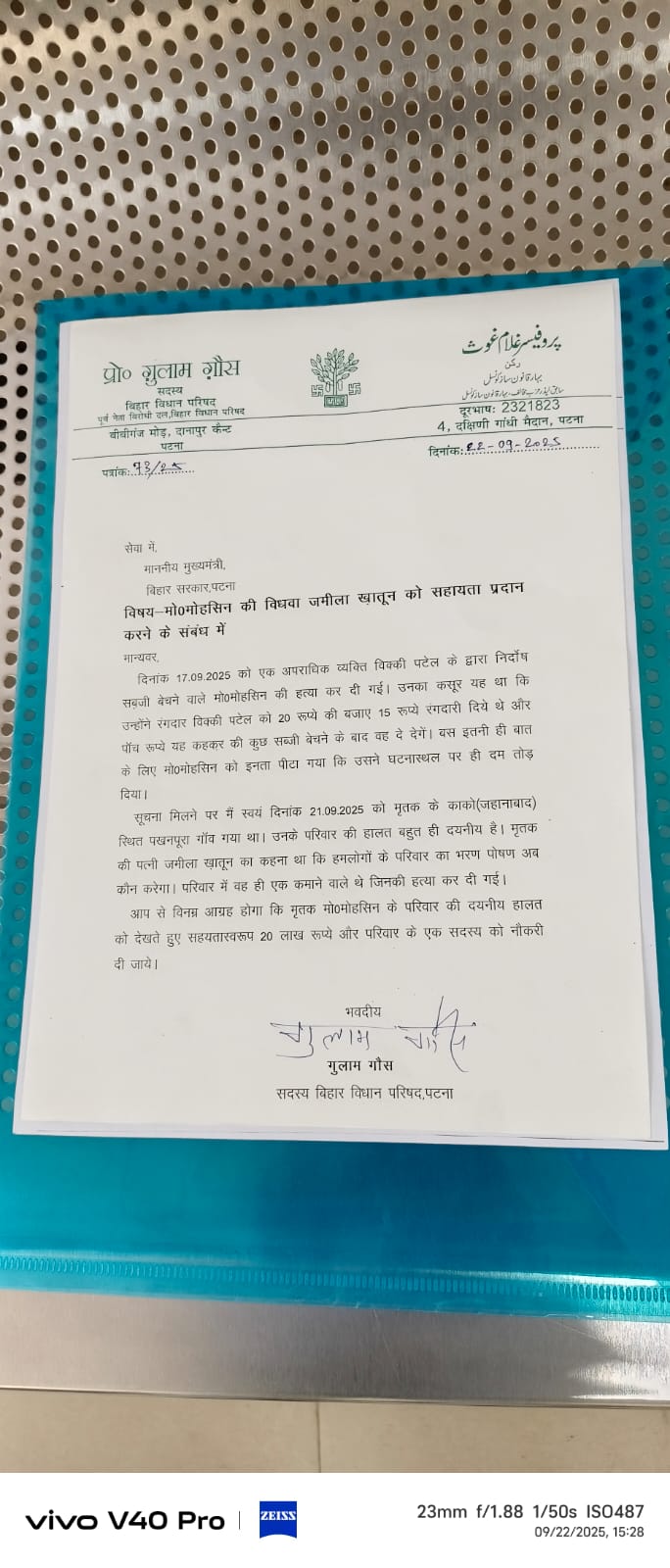

On September 23, MLC Ghulam Ghaus visited the family and wrote to the chief minister seeking Rs 20 lakh in compensation for the widow and a government job for a family member.

Wider Patterns of Indifference

Across India, incidents of public indifference to violence against Muslims and Dalits surface with disturbing regularity. Outrage often erupts online, but on the ground, silence prevails.

“What happened in Kako is part of a larger climate. There is a growing normalisation of violence in public spaces and an equally growing acceptance that ordinary people should stay quiet. This silence, whether out of fear or apathy, enables the violence to repeat,” said a rights activist from New Delhi.

The pattern is not unique to Bihar. In recent years, street vendors and small hawkers across India have faced rising hostility, often from the very authorities meant to regulate and protect them.

In Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh, hawkers have been assaulted during “anti-encroachment” drives, with viral videos showing police floggings of poor traders in public squares.

In Uttar Pradesh and Haryana, JCB excavators have been deployed to demolish market stalls and homes, frequently targeting Muslim vendors in the name of “illegal construction” or “encroachments”.

In Himachal Pradesh and Assam, Muslim hawkers have been beaten or stripped of their wares by mobs, accusing them of trespassing or being “outsiders”.

Each of these incidents may appear localised, but together they reflect a structural reality. A Delhi-based sociologist, who wished not to be named, points to a broader pattern: the normalisation of violence against the poor in public spaces.

“The invisibility of street vendors, their lives treated as disposable, is a reflection of hierarchy embedded in Indian society,” said the academician.

The question that still lingers: what is the worth of a human life in a society that lets a man die for an amount not even enough to buy a cup of tea?