Shah Khursheed, TwoCircles.net

Srinagar: Bareera, 24, a postgraduate student from Pulwama, remembers the first signs of something being wrong with unsettling clarity. In Class 11, while living in a girls’ hostel in Srinagar, her periods suddenly stopped. One month passed, then another. The silence of her body frightened her. She whispered her worry to her roommate, who tried to calm her, but the unease never left. When she returned home for the holidays, her mother noticed her anxiety and took her for a medical check-up. That’s when she had her first ultrasound, the day her quiet fear took shape.

“When the doctor told me I had PCOS, I broke down completely. I didn’t understand what it meant, only that my body was changing in ways I couldn’t control. The acne, hair fall, and irregular periods made me feel like I was disappearing piece by piece. The fear that I might never become a mother haunts me every day,” she said.

Across Kashmir, her story is far from unique. Behind closed doors, young women grapple with the hidden weight of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). The physical symptoms such as sudden weight gain, acne, facial hair, and irregular periods are only part of the struggle. Social stigma, beauty standards, and family expectations turn everyday life into a battlefield of anxiety and self-doubt.

Saikela Jan, 21 (name changed), from Srinagar’s Hazratbal area, describes the quiet torment many live with. “I kept my missed periods a secret for months. I was too scared people would think something was wrong with my womanhood. Facial hair, acne, and irregular cycles have made me shrink from the world. It makes me feel less feminine,” she said.

“I feel ugly and fat when I see myself in the mirror, so I stay away from social media and avoid going out with friends. I stopped taking pictures because I no longer see the old me,” she added.

Beyond the Diagnosis

A study by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), led by Dr. Mohd Ashraf Ganie at the Sher i Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (SKIMS), revealed an alarmingly high prevalence of PCOS among Kashmiri women. Conducted between 2013 and 2015, it surveyed 964 women aged 15 to 40 across five districts. The findings showed that 46.4 percent were probable PCOS cases, with 35.3 percent confirmed under the Rotterdam criteria, 28.9 percent under NIH criteria, and 34.3 percent under the Androgen Excess (AE PCOS) criteria.

A parallel study by the Department of Social Work at the University of Kashmir found that over 30 percent of women met the Rotterdam criteria, significantly higher than the national average. Sedentary lifestyles, poor dietary habits, and hormonal imbalances were identified as key factors. Many women also experienced metabolic issues such as obesity and insulin resistance, alongside psychological challenges like anxiety and depression.

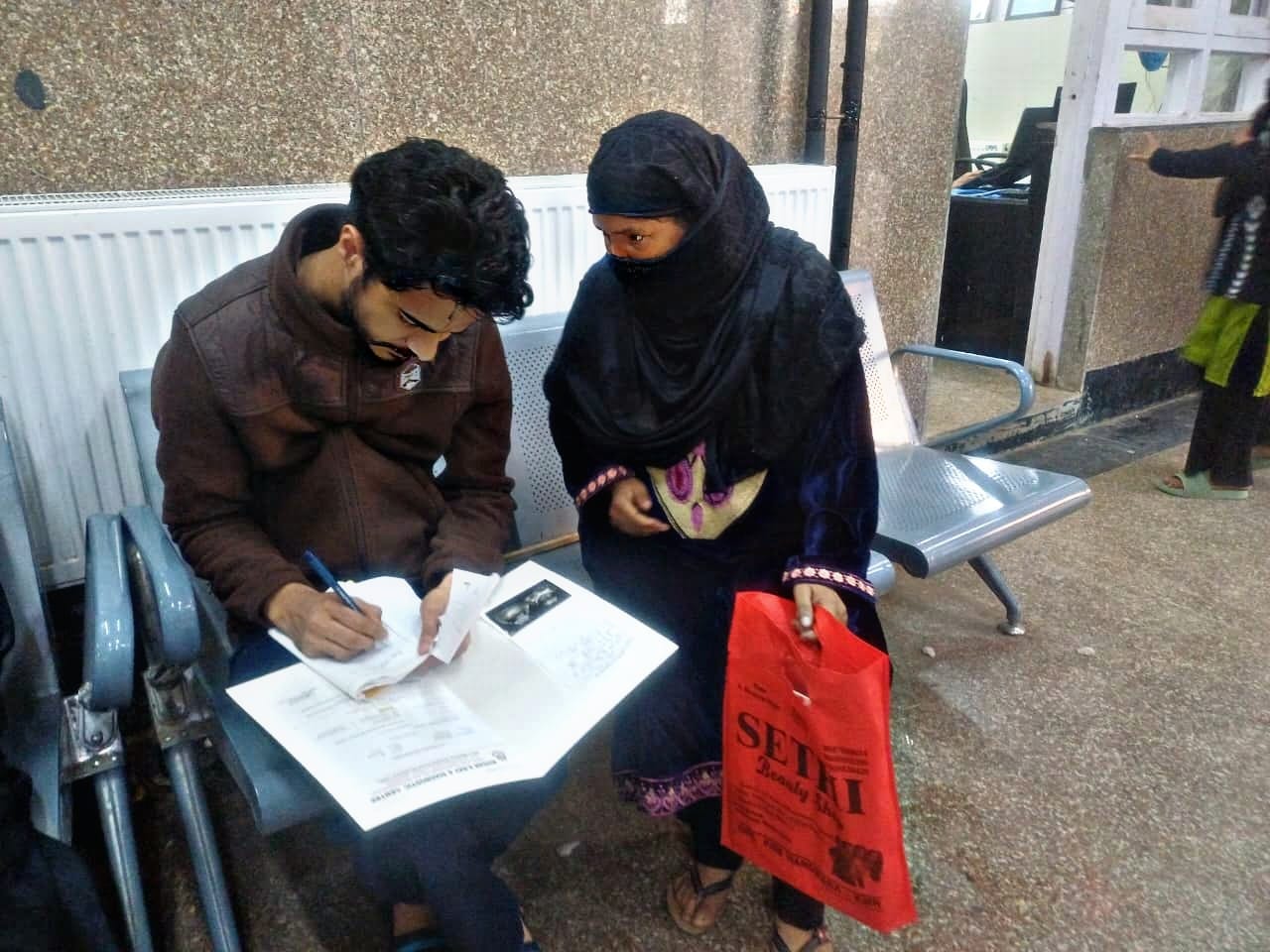

Iqra Nazir, a senior scholar in the Department of Social Work, spent two months at Sub District Hospital Hazratbal uncovering these hidden struggles. Her study focused on teenage girls aged 15 to 20, exploring how PCOS affects emotional well-being, body image, family relationships, and coping strategies.

“Families often perceive PCOS as a threat to marriage prospects rather than a medical issue. Once a girl is diagnosed, many parents turn to Peers or faith healers for quick solutions. Stories of healers helping couples conceive fuel hope, and families cling to that belief,” Nazir said.

She observed that the weight of stigma, society’s judgment, family anxiety over marriage and fertility, and rigid beauty standards often crush young girls more than the condition itself. The psychological toll is immense. Depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and social withdrawal accompany the physical changes, forming a cycle of silent suffering. Yet these girls remain largely invisible, their pain unnoticed.

Behind Luck Lies Neglect

Every morning, the waiting area outside the gynaecology ward at Government Medical College Handwara fills up long before doctors arrive. Young college girls clutch medical reports while newly married women wait quietly for answers.

Inside one consultation room, Dr. Shakir Khan, MBBS, MD (Gynaecology and Obstetrics), Senior Resident at GMC Handwara and Director of the Syeeda Memorial Charitable Health Foundation, begins another long day. “Every second or third woman I see now has PCOS,” he said, flipping through case files. “What worries me most is how silently it spreads. Most don’t realise what’s happening to their bodies until it’s too late.”

He recalls a 22-year-old student from Kupwara who came with acne and hair fall, having ignored her irregular periods for two years, assuming stress was to blame. “When I told her it was PCOS, she looked surprised and said many of her friends had delayed periods, she thought it was normal. That moment showed how unaware young women are. They dismiss early signs, not realising it’s their body’s way of asking for help,” he said.

The emotional impact, Dr. Khan added, is often as heavy as the physical one. “One woman who had been trying to conceive for years told me she thinks it’s her problem. PCOS changes how women see themselves. They start feeling unattractive, unworthy, as if their bodies have betrayed them.”

He remembers a 30-year-old schoolteacher labelled “banjh” by her community. Her irregular periods were dismissed as normal. When tests revealed severe PCOS with insulin resistance, the truth was clear. It was not luck, it was neglect.

Dr. Khan started her on a structured care plan with dietary changes, stress management, and medical therapy. Months later, she returned holding a newborn in her arms. “That moment reminded me that healing is not just about medicine, it’s about restoring a woman’s faith in herself.”

PCOS and Delayed Marriages Threaten Kashmir’s Fertility

Kashmir is facing a demographic challenge as rising PCOS cases coincide with social shifts. The condition, which can impair fertility, affects women across the valley, while delayed marriages driven by higher education, career ambitions, and cultural practices further reduce the window for childbearing.

A 2022 local report highlighted that nearly 50,000 women in Kashmir have crossed the conventional marriageable age, including over 10,000 in Srinagar alone. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS 5, 2019–21) shows that Jammu and Kashmir’s Total Fertility Rate has fallen to 1.4, well below the replacement level of 2.1.

Experts warn that the combined effect of rising PCOS prevalence, delayed marriages, and declining fertility could shrink the youth population, accelerate demographic aging, and create long-term social and economic pressures. Without timely intervention, these intertwined trends pose a serious threat to the valley’s population growth and generational balance.