Swastika Verma, TwoCircles.net

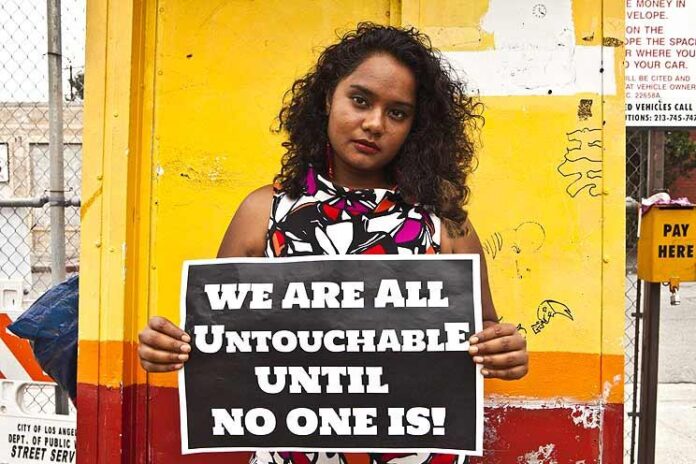

New Delhi: Feminism in India remains a tender and often misunderstood subject. Half the population is unfamiliar with its meaning, while the other half feels obligated to support it, often without fully understanding what it entails. Within this space, Dalit feminism exists as a separate and deeply layered struggle. Women who face both caste and gender-based oppression find themselves constantly challenged. Even after achieving education, employment and upward mobility, they are often reduced to symbols of shame tied to their identities.

Appearances often mislead. Behind a smiling face or a reserved demeanour, there can lie a truth or a lie, both equally heavy to carry. Caste identities in India are frequently judged by external attributes such as skin tone, speech, dress and bearing.

In the short stories of Telugu writer and scholar M.M. Vinodini, readers encounter women who seek only to live with dignity and ease. But their simple dreams are shattered when they face the weight of patriarchal expectations and social prejudices that erode their confidence, and sometimes, their will to live.

The protagonist of ‘The Parable of the Lost Daughter’, published in 2008, highlights the role of appearance in a caste-stratified society in Andhra Pradesh.

Suvarthavani, a young, ambitious Dalit Christian woman, possesses features – fair skin, a high forehead and a sharp nose – often associated with the upper caste. She embarks on a journey of self-awareness as she begins to question her admiration for the upper caste lifestyle, which she had earlier absorbed while presenting herself as a socially aware and educated woman.

She is drawn to the cultural polish and comfort of the upper caste world. Her parents, a rickshaw puller and a sweeper, did everything within their means to educate their daughter, whose beauty marked her as “different” in the eyes of others. That difference gave her a sense of entitlement not shared by other girls from her community.

Vinodini, who is also an educator, illustrates how education can unlock opportunities for Dalit girls like Suvarthavani. Nevertheless, it can also create distance – fostering a false sense of superiority, especially in those presumed to be from privileged backgrounds simply because of how they look.

In the early part of the story, Suvarthavani’s childhood is described through her yearning for inclusion in the upper caste world. Her innocence leads her to internalise feelings of shame for her Dalit Christian identity and develop a growing discontent with her family and community.

Suvarthavani’s identity alienates her in multiple ways. Her caste and class place her at a disadvantage, and her religion isolates her further. Her classmates wear ‘Bottu’ (a decorative or sectarian mark, often a dot or tilak) on their foreheads, while she wears a cross. Her education and appearance encourage her to dream beyond her circumstances. Her parents, Paladasu and Krupamma, always hoped for a better life for her. But she begins to resent her roots. She is often mistaken for a girl from the Kamma or Reddy communities, which makes her feel validated.

“We thought she was a Kamma or a Reddy, does not look like a Harijan girl at all!”

These comments comfort Suvarthavani, and she takes pride in them. Her home, her people and her background, all begin to feel small. She becomes determined to leave that world behind.

Her teenage years are shaped by her admiration for her friend Gayatri’s family. But her adoration blinds her to the subtle but persistent disapproval shown toward her. The first hint appears when Gayatri hesitates to bring Suvarthavani home because of her lack of a ‘Bottu’. Remarks about her appearance such as “not looking like a Harijan” reinforce caste stereotypes. She, however, sees them not as insults but as barriers she must overcome.

As she enters university and begins to study Humanities, she gradually becomes aware of caste-based discrimination. The turning point in her journey comes when she stays at Gayatri’s home after her marriage and confronts firsthand the intersection of caste and gender exploitation.

Her stay brings clarity. She notices the abusive behaviour of Gayatri’s brother-in-law, as well as the contradiction between image and reality in Gayatri’s father, Subramanium, who is a writer known for addressing caste and gender issues. The longer she stays, the more aware she becomes of the hypocrisy and moral decay behind the upper caste respectability she once admired.

One moment that lingers is Suvarthavani’s fear of menstruating while staying in her friend’s orthodox Brahmin household. In her Dalit Christian upbringing, there were no taboos around menstruation. But in this space, the natural biological process becomes a source of anxiety. It highlights how cleanliness and purity are weaponised to marginalise both women and Dalits. The community she comes from has historically dealt with the literal and symbolic filth of society. Cleanliness remains a privilege denied to many.

Her awareness deepens when the brother-in-law makes vulgar comments about the supposed sexual openness of Dalit Christian women. He maintains a respectable image publicly but makes clear that he sees Suvarthavani as someone he can approach for an affair even without consent.

Through this character, Vinodini reveals how Dalit women are often seen as property, echoing a historical pattern where “upper caste” men felt entitled to exploit “lower caste” women without consequence.

Suvarthavani’s understanding of Subramanium also shifts. She hears him routinely abusing his wife, comparing her to a Christian woman and questioning her character. For men like him, caste and gender are topics to romanticise in literature, but their personal lives reflect deep-seated violence and orthodoxy.

“She looked at the bookshelf and the rows of books he had written. There was nothing in common between the lofty words spoken by the protagonists of those books and the abuses that he uses just now\… He abuses her caste, her religion and the women and men of her community.”

This moment brings Suvarthavani a jarring realisation. The people she once admired live lives soaked in prejudice and hypocrisy. Their actions betray the very ideals they claim to uphold.

Vinodini’s narrative draws measured parallels between gender and caste, tracing Suvarthavani’s transformation. Her story shows how education, though empowering, can sometimes create illusions that lead individuals to believe that ticking off certain societal boxes offers protection from discrimination.

A woman who was both conventionally attractive and educated, Suvarthavani believed she could escape the trauma that defined the history of her community. But her story shows that deep-rooted prejudices do not disappear with appearance or achievement.

Vinodini also underlines how Dalits who turned to Christianity in hopes of escaping Hindu caste discrimination continue to face the same biases. Social conditioning and caste hierarchies remain entrenched, regardless of religion. Accepting one’s identity with clarity and pride is both a struggle and a triumph, and Suvarthavani’s journey of self-affirmation speaks to that powerful reckoning.

(Swastika is a Delhi-based writer committed to amplifying vulnerable and silenced voices through her stories. With a deep passion for both creative and academic literature, her interests span speculative fiction, Dalit writing, eco-criticism, disability studies and feminist literature.)