Shahzeen Khan, TwoCircles.net

Ranchi: Arrested as a terror suspect, a Muslim cleric in Jharkhand has recently been acquitted of all charges after nearly a decade-long legal battle.

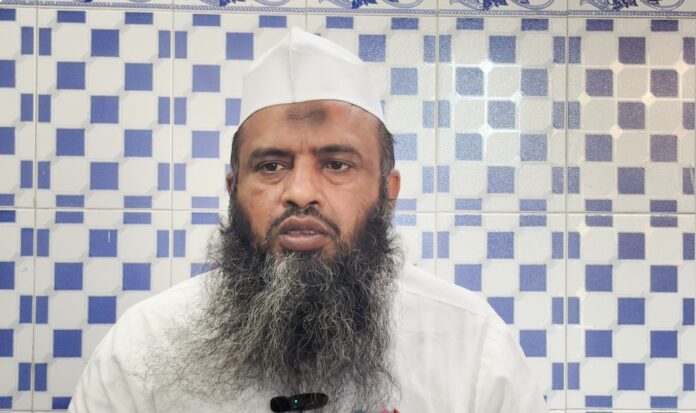

Maulana Kalimuddin Mujazahiri was arrested in 2016, along with two others, for alleged links to Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS). On February 28, 2025, a district court in Jamshedpur dismissed all charges against them.

The court’s decision came after 16 prosecution witnesses failed to establish their involvement. The accused were booked under the stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) based on “intelligence” provided by the Delhi Police’s elite Special Cell.

The case relied heavily on witness testimonies, but the prosecution failed to present any concrete evidence. According to defense counsel Balai Panda, none of the 16 witnesses could prove the accused’s involvement in the alleged offenses. With no material proof, the court ruled in favor of their acquittal and cleared them of all charges.

The case at a glance

Authorities claimed that Kalimuddin and his co-accused — Maulana Abdul Rahman Ali Khan (alias Maulana Mansoor) and Md. Shami — were part of a larger Al-Qaeda sleeper cell, accused of radicalising youth and planning an attack ahead of Republic Day in 2016.

However, Kalimuddin, who ran a small madrasa — Jamia Mohammad Bin Abdullah Madarsa — at his residence in Jharkhand’s Jawahar Nagar, denied these allegations. He insisted that his only work was teaching Islamic education to young students.

During TCN’s visit to Kaleemuddin at his madarsa, around 50 young boys and girls were seen diligently memorising their Quranic lessons.

Despite the lack of concrete evidence, Kalimuddin was arrested in September 2019 from a Kolkata residence by the Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS). He spent 14 months in jail before securing bail in November 2020.

Meanwhile, Shami was arrested in Haryana’s Mewat in 2019 and Mansoor had been in custody since 2015.

‘Worst days of my life’

For Kaleemuddin’s 28-year-old son Mohammed Huzaifa, the ordeal remains difficult to comprehend. “How does one make sense of a crime that was never committed in the first place?” He narrated the alleged brutal treatment he and his father had to endure.

“I was 19 years old when I was arrested from my home. It was a terrifying scene. I was blindfolded and taken to an unknown place. My father and I were kept separately in dark cells. They used to clip our fingers and administer electric shocks. It was the worst time for me and my family,” he alleged.

He added that during his detention, officers repeatedly pressured him to confess to plans of traveling to Pakistan, even though he had never even applied for a passport.

“They insisted I was about to leave for Pakistan. I had never even left India in my entire life. Yet I read in newspapers that I had traveled abroad,” he said.

After four days of detention, Huzaifa was released from police custody. However, his father remained in jail for about a year, leaving their family in distress.

A 54-page Jamshedpur court judgment later confirmed that the police had no evidence against the cleric from the very beginning. “Yet, they were taken into custody,” the court observed.

‘I always had faith in judiciary’

Reacting to the court’s judgment, Kalimuddin said he never lost faith in the judicial process. “I always believed the court would examine the facts. The police and the media can claim anything, but courts rely on evidence. The judge listened carefully to the witnesses and reviewed the case thoroughly before reaching a decision,” he said.

However, Kalimuddin narrated the impact these accusations had both on his personal and professional life. “The police seized my belongings and shut down my madrasa. Despite multiple court applications, I have not yet received my confiscated items back. We survived with the help of some generous people who supported us financially during those difficult times,” he said.

‘Media trials ruined our lives’

Kalimuddin accused certain sections of the media of making baseless claims about his arrest. “One of the officers told me, ‘Look, how the media is writing about you. They say you have links with Al-Qaeda.’ Based on these reports, I was treated like a hardened criminal even before the court passed a judgment.”

Responding to media claims that he had hosted Al-Qaeda meetings and conducted arms training, Kalimuddin asked, “If any of this were true, why could not the ATS find a shred of evidence? Why did my neighbors — who have known me for years — never report anything suspicious?”

“Just because a newspaper prints something does not make it true,” he added.

UAPA and its ‘abuse’

The UAPA allows authorities to detain individuals without establishing a substantial case. Critics argue that the legislation has become a “tool of intimidation” against underprivileged communities. Law enforcement agencies are not required to build a concrete case before labeling someone a terrorist, making it an effective instrument of repression against marginalised groups.

A Sabrang India analysis found that bail orders under UAPA are often legally stronger when granting bail than when denying it. Denial orders frequently rely on prosecution narratives rather than clear legal reasoning.

A Sessions Court in Delhi, for instance, has repeatedly denied bail to individuals accused under UAPA, including those allegedly involved in the February 2020 North-East Delhi riots. Activists such as Umar Khalid, Khalid Saifi, Meeran Haidar, Athar, Shifa Ur Rehman, Salim Khan, Shadab, Gulfishan, including others, were denied bail simply because their anti-CAA protests included calls for road-blockades.

Arrests under UAPA and convictions

During the 2023 Monsoon Session of Parliament, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) was compelled to disclose UAPA-related data. Between 2016 and 2018, 3,974 individuals were arrested under the stringent anti-terror law. A total of 3,005 cases were registered. However, only 821 chargesheets were filed during this period.

With such a low conviction rate, there are concerns about the indiscriminate use of the UAPA among rights groups, with many believing that the law is often used as a form of pretrial punishment, particularly in cases involving minorities.

A pattern of ‘abuse’

Maulana Kalimuddin’s case is not an isolated one. Over the years, several individuals — especially from minority communities — have been falsely implicated under the UAPA, only to be acquitted after prolonged incarceration, destroying several precious years of their lives.

One of the most glaring examples is the case of journalist Siddique Kappan, who was arrested in 2020 while traveling to cover the Hathras gangrape case. Despite no concrete evidence against him, he spent nearly two years in jail before being granted bail.

Another example is the arrest of activist Umar Khalid, who has been in jail since September 2020 under UAPA charges related to the Delhi riots. His bail pleas have repeatedly been denied, despite the absence of direct evidence linking him to violence.

Torture, isolation and a life in ruins

While law enforcement agencies close cases of wrongful arrests after a verdict is rendered in favour of the accused, the personal and social life of the accused often remains in ruins. Social stigma, financial ruin and psychological trauma continue to haunt them long after their release.

“Even your own relatives start to distance themselves after you are accused of such serious charges,” said Kalimuddin, adding, “In my case, many of my relatives kept their distance and abandoned us.”

Huzaifa, who now teaches at his father’s Jamia Mohammad Bin Abdullah Madarsa, says his father’s wrongful imprisonment disrupted their family’s livelihood.

“Our madrasa was shut and my father’s reputation was ruined. Before his acquittal, people continued to associate him with false terror accusations,” he said. “Who will compensate for these lost years? Who will compensate for our lost reputation?”

As UAPA cases continue to rise in India, policy experts and human rights advocates are calling for urgent reforms to prevent the law’s “misuse”. Until such changes are made, cases like Kalimuddin’s stand as grim reminders of a justice system that often punishes the innocent long before proving them guilty.