A Dalit Groom Rides a Horse Under Police Protection in MP, Challenges India's Caste Status Quo

Akansha Deshmukh, TwoCircles.net

A wedding procession moves along a kaccha road of Bharatpura, a remote village in Madhya Pradesh's Chhatarpur district. On both sides, humble huts stand silent witnesses to the procession, with many people choosing not to join the baraat, an Indian celebratory wedding procession that escorts the groom, but instead peering out their doorways, their curious gazes fixed on the 25-year-old groom, Lacchi Ahirwar, as he rides on a mare.

A man secures the reins to the mare, and two band members blow trumpets, while a lone police officer silently guides the baraat. While his presence is essential for security, it gives the procession a sombre tone. Lacchi is worried.

Lacchi's concern stems from the fact that he is a member of the Dalit community, which accounts for 16.6 percent of the Indian population yet continues to endure violence, intimidation, and prejudice across the country.

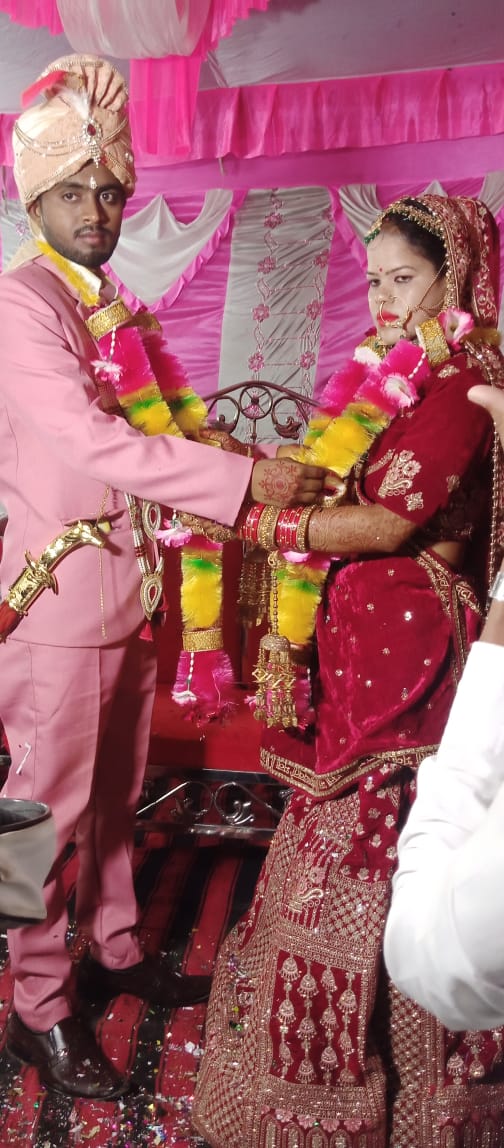

[caption id="attachment_449194" align="aligncenter" width="504"] wedding photo by special arrangement[/caption]

wedding photo by special arrangement[/caption]

Dalit Groom's Family Request Police Protection for Wedding

While most normal families would be busy with wedding preparations, Lacchi's uncle, Kaanshiram Ahirwar, 52, had gone to the Bijawar police station a day before the wedding on 27 June to file an application requesting police protection for his nephew's wedding procession, concerned that upper caste people in their village might cause problems.

"I was afraid they would come to the wedding and create a disturbance as they do at other Dalit members' weddings, which is why I went to submit the application," Kaanshiram explained to TwoCircles.net, adding that the upper castes do not allow them to celebrate functions.

There are around 250 Dalit families in the village.

[caption id="attachment_449188" align="aligncenter" width="457"] Dalit groom’s family seek police protection for wedding procession (Photo: Special arrangement)[/caption]

Dalit groom’s family seek police protection for wedding procession (Photo: Special arrangement)[/caption]

Fearing reprisal, the Dalit family did not name any members of the upper castes during the entire conversation with this reporter. The term "they" is a collective designation for members of upper castes, representing a clear split between the two communities.

"To be honest, I'm scared even as I speak to you," Lacchi told TwoCircles.net, adding that if he says anything about the upper castes, they will come after him.

'Climbed the Mare Despite Fear': Dalit Groom

On his wedding day, his family and he were both afraid. "I climbed the mare despite my fear. It was my wedding, and I had to perform all the rituals," he explained.

Dalit men like Lacchi are not "allowed" to ride a horse to their wedding by upper-caste people, and in some regions of India, even sporting a moustache is not allowed. Keeping a moustache can turn fatal.

In the neighbouring state of Rajasthan in 2022, a 28-year-old Dalit man was stabbed by upper-caste men for sporting a moustache. He died from his injuries by the time he was taken to the hospital.

By riding a horse on his wedding day, Lacchi intended to give the message that Dalits are equal to the upper castes. "Even we can do what they can do," he told TwoCircles.net.

"There was no violence. Everything concluded peacefully," said Swaroop Upadhyay, an inspector with the Bijawar Police Station who personally attended the wedding to ensure there was no disruption.

While Lacchi appreciated having the police there to protect him and his family, he wished there had never been a need for police action in the first place.

‘Dalits Face Legal Obstacles While Filing Cases’: Lawyer

Rani Gawli, a 37-year-old lawyer in Madhya Pradesh, feels that unless the authorities take firm and immediate action against those responsible, the cycle of violence and injustice against Dalits will continue.

"Unfortunately, it appears that local leaders and even police officers who wield influence over these cases foster an atmosphere of impunity, which emboldens the attackers," she said.

Dalit people, according to Gawli, face obstacles when seeking to file complaints.

Lacchi concurs. "Even if we file complaints against the village's upper castes, nothing happens. They have everyone's support," he remarked.

Raising Attacks on Dalit Weddings in Madhya Pradesh

In recent months, there have been numerous attacks on Dalit wedding processions, which highlight the deep-seated discrimination faced by the Dalit community.

Saurabh Garg, brother of the self-styled godman Dhirendra Krishna Shastri, was caught on camera brandishing a pistol at a Dalit woman's wedding in February.

In early June, a Dalit man's wedding procession was pelted with stones in Madhya Pradesh's Chhatarpur district because the village's dominant caste objected to the groom riding a horse. A month before, people pelted stones at a Dalit groom riding a mare in his baraat in the state's Dewas district. They continued to hurl abuses and thrash the guests until the groom dismounted the mare and sat on a motorbike.

In another incident, upper caste members attacked guests during the wedding of a Dalit man who served in the Border Security Force (BSF) in Madhya Pradesh's Mandsaur district.

Similar incidents have been reported in the Rajgarh district, where a Dalit wedding procession was stoned, leaving four attendees severely injured, and another where upper caste people prevented a Dalit groom's procession from using a music system and ransacked the wedding venue. Similar incidents have occurred in Madhya Pradesh's Ujjain district in the past.

A Rise in Atrocities Against Dalits in Madhya Pradesh

According to a National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report, Madhya Pradesh had a higher number of Dalit atrocities against women and children. The state had the highest number of registered instances involving similar offenses.

In 2021, there was a significant increase in cases of Dalit atrocities compared to the previous year. A total of 7,214 cases were registered specifically under Dalit atrocities. Furthermore, there were 4,627 instances reported under the SC/ST Act in 2021, a 9.38% rise from the previous year.

Akansha Deshmukh is an independent journalist covering crime, politics and communalism.