A woman, a Muslim, and an artist: How a 23-year-old in Delhi’s Jamia Nagar is expressing politics through art

23-year-old Anjum, who lives in Jamia Nagar, a middle-income Muslim-majority enclave near the Yamuna River in Delhi, has been actively involved in art-based community projects in her neighbourhood for the past three years.

Arbab Ali | New Delhi

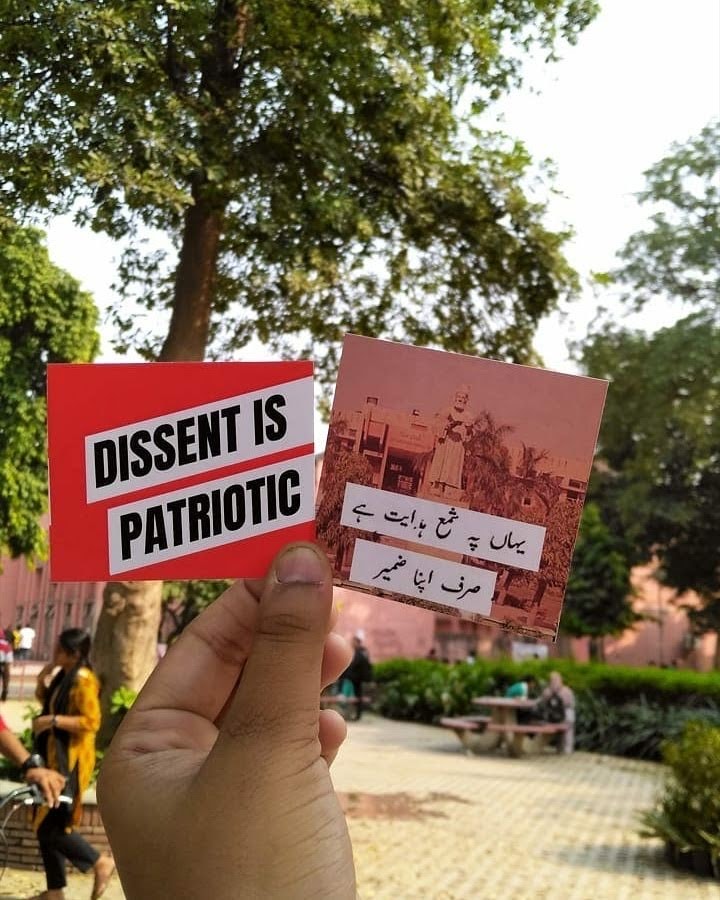

NEW DELHI — If you’ve met young activists at recent protest rallies in Delhi, you would’ve noticed tiny badges pinned onto their bags or T-shirts. These aren't your typical pin badges. On a red background, in white capitals, is a rather offensive one-liner: "I read banned books" or "Dissent is patriotic".

Having discovered them at a protest march last December, I decided to order four badges from their designer, 23-year-old artist Simeen Anjum.

I met Anjum on March 6 outside the Sukhdev Vihar Metro Station in southeast Delhi. She was carrying a tote bag over her left shoulder and a backpack that appeared heavy for her height. "I've got my paints in the bag," she said, turning down my offer to help her carry it as we walked 50 meters towards a tea stall for a conversation about her art-meets-activism entrepreneurship.

Anjum, who lives in Jamia Nagar, a middle-income Muslim-majority enclave near the Yamuna River in Delhi, has been actively involved in art-based community projects in her neighbourhood for the past three years. Anjum's interest in the arts began when she was in elementary school and only grew after she enrolled in the Bachelor of Fine Arts programme at Jamia Millia Islamia. “Later, while in college, I began making handmade products and selling them online to support myself and pay for my art supplies,” she said.

[caption id="attachment_448562" align="aligncenter" width="651"] Anjum painting walls in Kochi, Kerala | Photo by special arrangement[/caption]

Anjum painting walls in Kochi, Kerala | Photo by special arrangement[/caption]

Anjum now sells on Amazon, as well as on her website and Instagram page, both titled "Simy’s Handmade," where she also accepts custom orders.

Anjum claims that in art programmes, students are only taught drawing and sketching techniques, and the subject is not viewed as a means of earning money. "When I was doing BFA, my family didn't expect me to make money," she explained. Anjum's family was opposed to her pursuing a career in the arts. "We come from a middle-class family, and my parents never had access to art,” she said.

Jamia violence and Anjum’s resistance art on university walls

Anjum has a unique perspective as an artist who belongs to and lives in a Muslim neighbourhood. "My work tries to reflect the issues that we face as Muslims and as women," she said. Identity, gender, conflict, and healing are among her themes. Her work can be found in public spaces such as murals, graffiti, posters, and other forms.

In 2019, Anjum was in her second year at Jamia Millia Islamia when the Delhi Police stormed the campus, teargassed the library, and thrashed students. After this incident, Anjum would pick up her brush and begin painting murals while everyone else was on the road shouting slogans or giving speeches. "All of the art I created during that time came naturally from our surroundings and our experiences," she says.

[caption id="attachment_448563" align="aligncenter" width="685"] Pin badges and a t-shirt commemorating the infamous ‘Demonetisation’ of 2016 by Anjum and singer Poojan Sahil | Photo by special arrangement[/caption]

Pin badges and a t-shirt commemorating the infamous ‘Demonetisation’ of 2016 by Anjum and singer Poojan Sahil | Photo by special arrangement[/caption]

Anjum painted a portrait of JNUSU president Aishe Ghosh against a red background on one of the walls of Jamia Millia Islamia. Ghosh was attacked on the JNU campus on January 5, 2020. Another mural she created was an excerpt from Paash, a major poet in the Punjabi literature of the 1970s: “main ghaas hoon, main apanaa kaam karoongaa, main aapake har kie-dhare par ug aaoongaa”

Apart from Jamia, Anjum created graffiti and murals in other parts of the city where there were protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (the CAA), such as Hauz Rani and Old Delhi.

She worked with singer Poojan Sahil on a T-shirt project commemorating the second anniversary of the infamous 'Demonetisation' in 2018. "We sold t-shirts with the quote 'remember, remember, November 8th'," she explained. Apart from that, Anjum exhibits her products on college campuses, where she claims they are well-received. "Whenever there is a campus event, I try to set up a stall," she explained. However, the majority of her unique protest art merchandise is sold through word of mouth.

Painting cafe walls and selling home-made products

Anjum has kept her prices low so that her target audience — university students — can afford them. On her website, standard earrings cost between Rs 80 and 140, not including shipping. She receives 50-100 orders per month, and during the holiday season, the volume increases, requiring Anjum to work overtime to prepare the products.

Apart from painting walls during protests, Anjum works on a variety of commercial painting projects, for which she hires people on a project basis. In Jamia Nagar, with its thriving food and décor culture, you’re bound to come across one of her painted décor walls. She has painted the walls of Engineer’s Restro, a cafe run by Engineering department alumni of Jamia Millia Islamia at Tikona Park. “It takes me 3-4 days to paint a décor wall, and I customize it to the client’s needs,” she explained.

Anjum also sells home-cooked pastries, cakes, and chocolates boxed in beautiful shapes or alphabets, as well as home décor and party décor.

[caption id="attachment_448564" align="aligncenter" width="720"] Laptop and phone stickers made by Anjum | Photo by special arrangement[/caption]

Laptop and phone stickers made by Anjum | Photo by special arrangement[/caption]

Challenges of navigating the social media space for her products

Social media, she says, is “no longer a safe space” for artists like her “who come from two marginalised backgrounds, Muslim and woman”. She narrated how, in 2021, random people began commenting on her business page that she is an "anti-national" and that her business should be shut. Her work's political stance has an impact on her potential audience. "Perhaps I would have sold more," she reasoned.

Anjum also works with young students and underprivileged women, teaching them how to make crafts to sell and earn a living. She is currently volunteering with two non-profits in this capacity.

Her project was chosen for the Students Biennale Exhibition at the Kochi Muziris Biennale in 2020 and 2022, which is one of India's most prestigious contemporary art exhibitions. Anjum's proposal is to collaborate with young women her age to identify safe places for women to hang out in Kochi. The project, titled ‘I know a spot’, involves groups of women going on walks and identifying places where they could simply spend time in, feeling safe and comfortable. Anjum's other work, a photo essay about the use of the material tarpaulin in anti-citizenship protests, will be published soon as part of a book project on mapping resistance spaces around the world, commissioned by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung in Berlin.

Arbab Ali is a fellow with the SEED-TCN mentorship program.