Aditya Sharma, TwoCircles.net

New Delhi: When 33-year-old Khushboo Jaiswal walked into a private hospital in Delhi, she was expecting a calm and natural childbirth filled with gentle pushes and the rhythm of labour. Within hours, she found herself on an operating table.

“I was admitted to a hospital in Burari, Central Delhi, when my water broke at home. The doctor said my labour was taking too long, and normal delivery will not be possible. And therefore, they will conduct a cesarean section (C-section). My family agreed. Before I knew it, I was in the operation theatre,” she said.

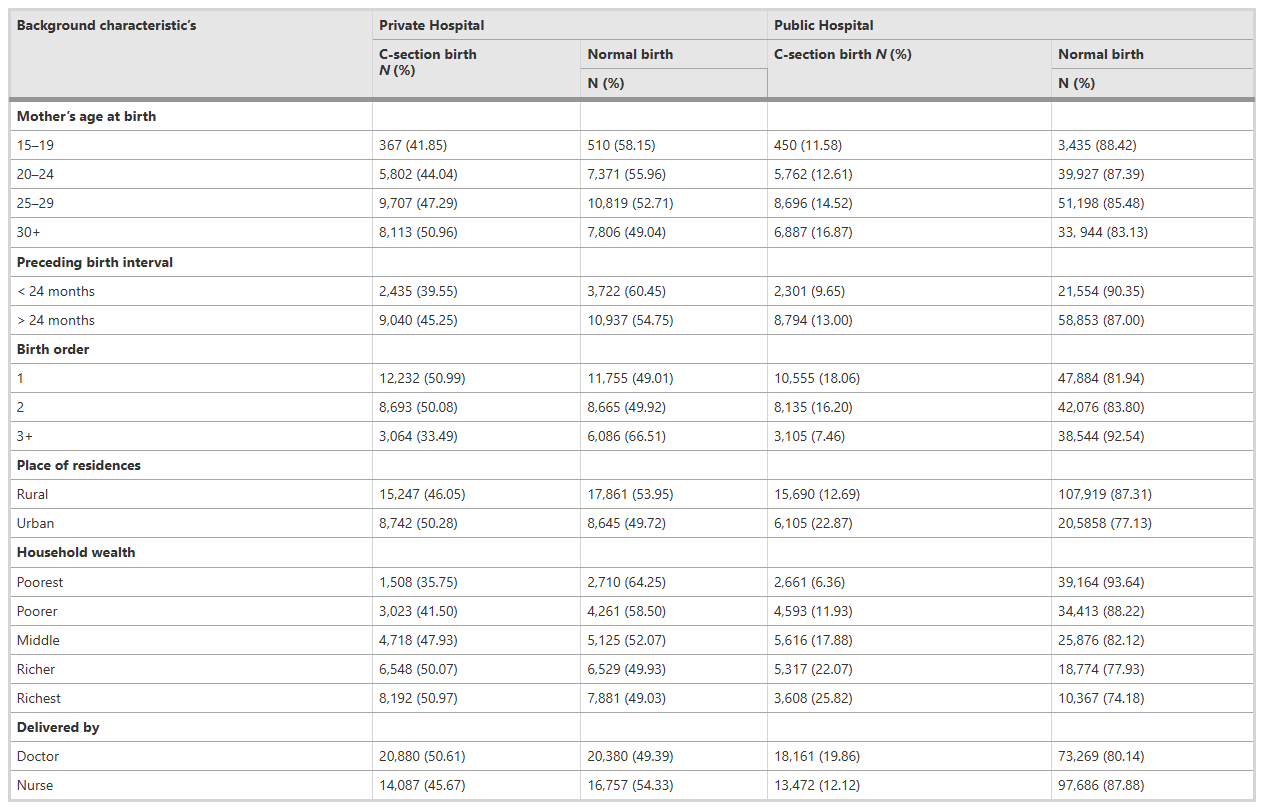

Her experience is now common across India. According to the National Family Health Survey-5 (2019–21), nearly half of all births in private hospitals (about 48 percent) happen through C-section. That number stands at 14.3 percent in government hospitals, already higher than the World Health Organisation’s guideline of 10 to 15 percent.

Khushboo said women are often persuaded toward surgery.

“Nurses and doctors scare you in such a way that they would say something that would make you nervous and try to persuade you for a caesarean since it is a quick 50-60 minutes process and is expensive; whereas, normal delivery takes 4-6 hours and cheaper than caesarean. I feel they (hospitals) just want to make money and so they prefer only caesarean. Even one of my relatives also went through the same situation,” she alleged.

Dr. (Prof.) Sadhana Kala, a senior obstetrician and gynaecologist, has observed this shift unfold for years. “A large part of the problem stems from profit-driven incentives. Hospitals and doctors often earn more from surgical deliveries than from normal births,” she said, adding, “There is also a shift in medical culture. Many obstetricians today prefer surgical interventions over waiting through prolonged labour.”

Childbirth across the country is being influenced by income, place and access. India’s caesarean birth rate has climbed over the past decade. The latest data from NFHS-5 shows that 22 percent of all births in the country are now through surgery. It is up from 17 percent five years earlier.

The highest rise is in private hospitals, where almost one in two babies is delivered surgically. Government hospitals record fewer such births. While doctors agree that C-sections are lifesaving in complicated pregnancies, the data shows that many surgeries are done even when it is not needed.

One in three births in cities happens through surgery. It is about one in five in rural areas. Wealthier women are five times more likely to undergo a C-section than those from poorer families. Education plays a role here. Women with higher schooling undergo more surgical births than those with little or none.

The pattern varies across the country. Southern states such as Telangana (60.7%) and Tamil Nadu (44.9%) record the highest rates, while Bihar (9.7%) and Nagaland (5.7%) remain among the lowest.

Once a natural process, childbirth now reveals the role of class, location and access, with surgical births becoming more frequent among those who can afford private hospitals.

Once a natural process, childbirth now reveals the role of class, location and access, with surgical births becoming more frequent among those who can afford private hospitals.

Shabnam, 29, another mother from a Delhi suburb, shared similar experience. During labour, she was told her baby’s heartbeat had slowed.

“There was no real discussion, and I was really scared for my baby. I was taken straight into surgery. I was pressurised by nurses or scared, I would say, it was a difficult situation for me,” she said.

Dr Sunita Tandulwadkar, president of the Federation of Obstetric and Gynaecological Societies of India (FOGSI), said the rise in C-sections must be understood in context. “According to data from national health surveys and institutional reports, the overall rate has increased in both public and private sectors, although the proportion remains higher in private facilities. It is important to recognise that this trend is multifactorial and reflects evolving clinical, demographic and social realities rather than a single cause,” she said.

“A major contributing factor”, according to her, “is the growing number of women with a previous caesarean delivery, who, for valid medical and safety reasons, frequently undergo repeat caesareans”.

The Hidden Costs for Mothers and Babies

While surgery saves lives, unnecessary C-sections bring medical and emotional risks. Women face longer recovery, infections and complications in future pregnancies.

A 2024 study in BMC Pediatrics that examined more than 2,00,000 Indian births found that babies delivered through c-sections were more likely to suffer from malnutrition, stunting and neonatal mortality compared to those born vaginally.

The researchers concluded that “non-medically indicated caesarean births” were linked to poorer child health outcomes and widening nutritional inequality.

Public health specialists have long said that too many surgical births can affect not only women’s choices but the health of their children.

Shabnam recalled how quickly her operation was decided. “The doctor said my baby’s heartbeat was slowing. I did not know what questions to ask,” she said.

Dr Tandulwadkar says expectations are changing among patients too. “Many women, especially in metropolitan areas, now prefer planned deliveries to avoid prolonged labour or emergency situations. Such preferences must be balanced with sound clinical judgment,” she said.

Her focus, she saif, is on medical justification and informed decision-making. “Every C-section must be based on evidence, with proper counselling and auditing. The goal is safe motherhood, ensuring that every woman receives the right mode of delivery for her specific condition,” she explained.

Policy and Practice

The Madras High Court in 2018 ordered the Health Ministry to investigate unnecessary caesareans in Tamil Nadu after reports suggested unusually high rates. Advisories were sent out, but no enforcement followed. Hospitals are not required to justify why a surgery was performed.

The rising rates of C-sections in private hospitals reflect the influence of commercial practices, regulatory absence and prevailing perceptions in urban healthcare.

On the clinical side, Dr. Kala highlighted that surgical births can affect newborns in multiple ways. “We are seeing babies born through surgery having more breathing difficulties immediately after birth, and in the long run, higher risks of obesity, allergies, asthma and weakened immune development. There are also occasional cases of accidental surgical cuts during delivery,” she said.

The doctor emphasised the need for systemic reform. “We must end financial incentives for C-sections and instead reward normal deliveries. Educating mothers to trust the natural process, allowing labour to progress and offering midwife-led care can all help. The goal should be safety, not speed or profit,” she said.

As India urbanises and private healthcare expands, these numbers may climb further unless governments, hospitals and communities act together.

Childbirth, doctors said, should rest on medical need, informed consent and respect for women’s decisions. For new mothers like Khushboo and Shabnam, that remains the hope to bring life into the world without fear or pressure and to be heard when it matters most.

At a Glance

India’s caesarean section rate now stands at 21.5%, exceeding the WHO’s guideline of 10-15%. The divide between private and public healthcare remains wide, with 47% of births in private hospitals are surgical, compared to 14.3% in public facilities.

Southern states lead the trend, with Telangana at 60.7% and Tamil Nadu at 44.9%, while Nagaland (5.7%) and Bihar (9.7%) record the lowest. Urban women (32%) are nearly twice as likely as rural women (17%) to undergo surgical births. Among the richest households, 39% of deliveries are surgical, compared to just 7% among the poorer households. Delhi records 23.6%.