By Somnath Mukherji,

Lovely is a strange name for a Sabar girl. But there are stranger things that happen in Amlashole. Lovely carries her 10 month old brother around who has a festering skin infection all over his body including his scalp. He is always drowsy and wants to rest his head on the strong shoulders of his 7 year old sister. The oldest sister, Shakuntala is 13 and runs the entire household since the passing of her mother. Their father Lulu Sabar is physically handicapped and walks slowly and like other Sabars of the area spends most of the day in the forest collecting vines, root tubers and wood which fetches him anywhere between Rupees 40 to 60 – barely enough to buy food and country liquor. On days without work things are worse. Their home is in a hamlet of 20 houses on the slope of a hill that forms part of the Amlashole village in West Mednipur district of Paschim Banga.

Lovely with her 10 month old brother

Sabars are hunter gatherers – gatherers really because hunting is banned and animals are hard to find in the forest. Sabars were classified as a criminal tribe by the British under the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871. Although they were graduated from notified to denotified tribes in 1952, the social stigma continues. Sabars are strange people, at least as we see them – they do not accumulate and they do not ask for things like rights, entitlements or representation. From the material belongings in a Sabar home it is impossible to guess how many people live there. In Lulu’s home a few clothes on a string hang listlessly, a torn blanket is scrunched up in the corner of the mud floor. Fire burns in the small hearth in the other corner boiling a pot of rice. With the exception of a few steel plates and a ladle there are no other utensils. This sustains a family of 6 in Shakuntala’s home and up to 10 in others.

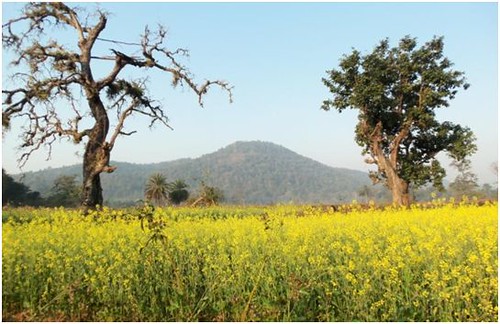

Village of Amlashole

Quite antithetical to our urban worldview, Sabars accumulate nothing – not even the root tubers from the forest that is one of their main foods, especially in times of scarcity. They gather only what they consume in a day. Perhaps they see nature to be not as fickle as we do. That is the only thing they depend on – nature; no services, no fossil fuels, no one’s cheap labour other than their own, no subsidies or fluctuating interest rates. The logic that drives their world seems completely alien to us.

I asked a Sabar woman in the morning if she was preparing to go to the forest, “Of course,” she replied, “What would we eat otherwise?” Eat? Amlashole came into the news in 2004 for several starvation deaths – another Kalahandi, another fixable problem, another outpouring of sympathy from people waking up to the fact that endemic hunger exists in India. From news reports it was never clear to me why the people of Amlashole had to starve. On asking around I repeatedly got one unambiguous answer – they were stopped from going into the forest! They could not gather food, fuel and things by which they earn their livelihood. They were barred by the security forces patrolling the forests – the forest that sustains their lives, the forest on which we claim not to depend on; the forests of Saal, Shegun, Mahua, Tendu and so many other herbs and roots the names of which are beginning to appear on packaged tea bags and ointments in cities all over the world – straight from mother nature! None of the Sabars or the Mundas said the famine was due to lack of development or non-functioning Anganwadis and ration shops or dysfunctional Yojnas and schemes. I had to restrain my urban eagerness to interview the families where deaths had happened – many people have already made careers out of Amlashole.

Sabars depend mainly on the forests

Today the road to Amlashole is surprisingly well paved, an elaborate CRPF encampment stands out, one-room brick houses are being constructed for the Sabars and handpumps are being installed. A big transformer sits in the middle of the Sabar-Munda mixed village and one can trace the lone twine of a wire entering Lulu’s home through a hook like pipe on the roof. Amlashole is connected today! “All of this happened after the Anahar (famine),” explained a Munda resident. He pointed to a primary school building down in the valley and explained how speeches were made in Bangla and Hindi by people who flocked Amlashole after the famine.

Dinner was being cooked when I went to Indra’s home. “Junglee Aloo,” they explaned. A pot full of tuber roots for perhaps 8 to 10 people in that home. “Very good,” he explained, “The roots also have medicinal value – good for your body!”

A woman pulled out a Saal leaf and started taking out pieces for me and my friends. I tried to persuade them to limit their generosity to a piece because while it was a sampling for me it was their entire dinner. “Enough,” I said, “Keep some for yourself”.

While Mundas are engaged in agriculture Sabars depend mainly on the forests for their survival

“We have plenty,” they replied in unison.

Indra and many others from the village have several police cases registered against them. What harm they can cause to the Republic is incomprehensible to me. As if they don’t have enough to worry, they have to go to Jhargram to appear in court at a specified frequency – a journey that regularly costs them their daily earning and their trip to the forest.

As I ate the delicious tuber roots in a forest that shone under the full moon, I wondered if it was our presence or absence that hurt them more; whether their way of living was a problem for them or for us; whether passive neglect was better than an active process of dispossession.

—–

Somnath Mukherji is a volunteer with Association for India’s Development (http://www.aidindia.org )