By Kashif-ul-Huda, TwoCircles.net,

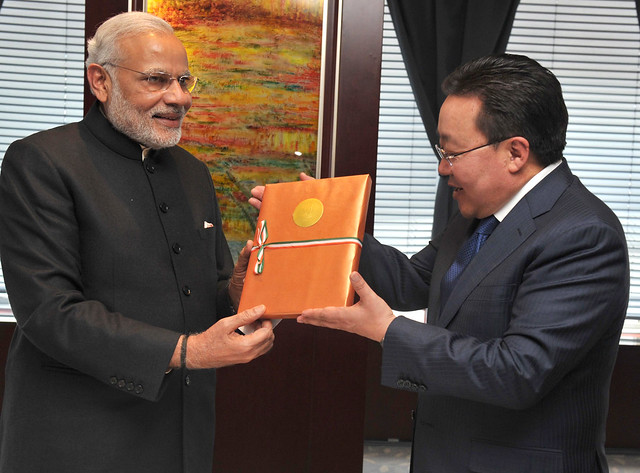

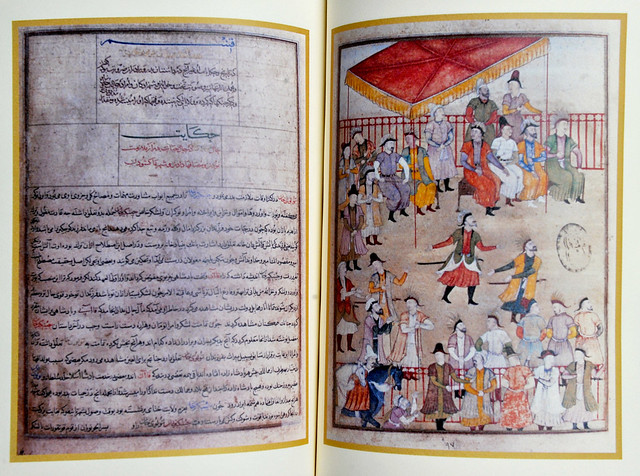

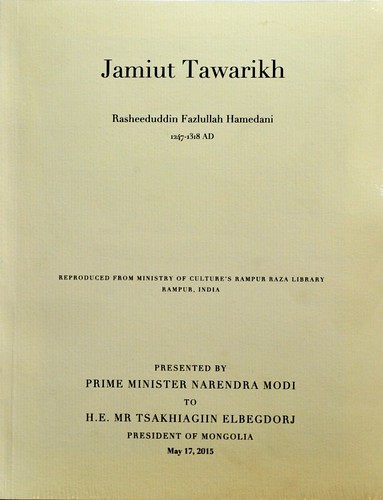

Last Sunday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi handed a beautiful and thoughtful gift to the President of Mongolia Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj. It was a copy of the earliest illustrated Persian work on the history of Mongol tribes. The book called ‘Jame at-Tawarikh’ (Collection of Histories) was authored by Rashiduddin Fazlullah Hamdani [1247-1318CE], who was the Vazir of Mongol king Mahmud Ghazan Khan [Reign 1295-1304].

Ghazan Khan, who was raised as a Christian, converted to Islam and adopted a tolerant attitude towards different religions practiced by people he governed. Rashiduddin came from a prominent Jewish family of Hamdan and he also became Muslim in his youth. He was commissioned by Ghazan Khan to write a history of Mongols but Hamdani expanded the scope of his work to make it the first known history of the world. Only some portions of this three-volume book have survived, now dispersed throughout the world.

Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi’s gift to the President of Mongolia, Mr. Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj, in Mongolia on May 17, 2015.

It is important to note that Ghazan and Rashiduddin chose Persian as the language for this epic project. Farsi or Persian was the language of communication, documentation, literature, and official business for a large part of the known world at that time.

The copy of the manuscript that Modi presented is volume I of the three-volume book. There are some portions of volume II and III in different collections but of volume I, “no other copy of it is known to exist,” informed the press release issued by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO). The original 13th century Persian manuscript with “over 80 fine miniature illustrations” is preserved in Rampur Raza Library, the oldest library of India which came into existence in 1774 with the personal collection of books of Nawab Faizullah Khan, founder of the Rampur State. Successive rulers of Rampur added to the collection and after the merger of Rampur to the Union of India, the library is managed by a board set up under the Ministry of Culture. The Library is now housed in a majestic looking Hamid Manzil in Rampur Qila (in Uttar Pradesh).

Azizuddin Hussain, director of the Library informed me that the request for the copy came from the PMO in March. Unfortunately, the library has no record of how Jame at-Tawarikh was acquired. Absence of acquisition record probably means that it was part of the library collection before 1857, suggested Hussain. But no one is surprised that a book of history written in Mongolia in Persian was housed in a library in India. India was part of the world that communicated and conducted official work in Persian. Persian arrived in India with Mahmud Ghaznavi [reigned 998-1030] and stayed as official language till 1837 when British colonial government replaced it with Urdu/Hindustani.

Not surprising therefore that Rampur Raza Library has a massive collection of Persian manuscripts. A few years ago, I visited the Raza Library at Rampur and was astonished to see the heavy security presence that in my view was very intimidating and probably keeping many people away from benefitting the library.

Perhaps, I was wrong. May be all libraries need to have heavy security because they are repository of our history and knowledge. Just three days before the Prime Minister of India handed over the copy of this manuscript to the President of Mongolia, about 11,000 books of Urdu Library of Munger were looted. Perhaps the saddest part of this story is that the library was not looted because someone found the books to be of great value. The looted books were dumped in Ganga as the looters were more interested in library building than the books it contained. It was a case of encroachment of buildings where the casualty was books.

A massive earthquake in 1934, immortalized in Mubarak Azeembadi’s nazm ‘Zalzala-e-Bihar’, killed over 10,000 people and destroyed many towns in Nepal and Bihar. Munger administration decided to rebuild the town and establish two libraries – one for Hindi and one for Urdu. Hindi Library closed after few years but Urdu Library has continued to function until now.

But why was there a need to establish two different libraries? Why not just one? To understand this, I will refer you to a paper published in 2008 by Dr Rizwan Ahmad, now a Professor of Linguistics in Qatar University. The paper titled “Scripting a new identity: The battle for Devanagari in nineteenth century India” was published in peer-reviewed “Journal of Pragmatics.” In this paper, Ahmad traces the history of separation of Urdu and Hindi.

In his brilliant paper, Ahmad demonstrates that argument in favor of Hindi (in Devnagri script) to be made the official language had begun to be made soon after the 1837 Act that replaced Persian as the language of the courts of law in North West Provinces and parts of the Central Provinces.

Even though Persian was used as the official language in India for over eight hundred years, the arguments in favor of Hindi was made by attacking the Persian script as error prone and susceptible to fraud. Urdu, a language that was birthed and developed in India and shares same linguistic roots as Hindi, was portrayed as foreign.

Ahmad writes about the convoluted arguments of petitions written to discredit Urdu. He writes about one such example that argued that “Urdu written in the Persian script is ‘semi-Persian’, because of Persian loanwords, and that ‘the Persian of our day is half-Arabic’, because of Arabic loanwords, so Urdu is Semitic in its essence.”

Ahmad explains, “notice how Shiva Prasad selectively chooses to define Urdu in terms of its borrowed vocabulary which is quite small compared to the native Indic vocabulary, rather than the linguistic structure that Urdu shares with Hindi, which linguists believe to be the defining feature of a language. In terms of Irvine and Gal’s model, this is an example of erasure; the shared linguistic history of Urdu and Hindi is being negated in order to construct Urdu as foreign.”

Of course, there were many Hindus who were proficient in Persian and for them Urdu was their own language. Urdu was declared foreign and language of vice and Hindi as virtue. Hindus who did their work in Urdu were denigrated. Ahmad writes how writers championing the Hindi cause explained Hindu speakers of Urdu: “Harishchandra dismisses the Hindu speakers of Urdu as simply ‘depraved sons of wealthy Hindus’. He does not stop at that; he, in fact, claims that even the depraved sons of Hindus speak Urdu only when ‘in the society of harlots, concubines, and pimps’. His claim is that real Hindus, Hindus of high moral strength, do not speak Urdu or speak in some debauched corner of society.

This process of eliminating sociolinguistic facts that do not agree with the ideology is an example of the semiotic process of erasure. Shiva Prasad, in a similar vein, succinctly claims, “Those who did not aspire or seek to gain the favor of the Muhammadans by becoming, if not altogether, half Muhammadanized, still valued Hindi works, left by Tulsidas, Surdas, Kabir . . .” Here again the goal is to explain away a painful sociolinguistic reality, quite derogatorily, by stating that only those Hindus, who in their lust for power had become half-Muslims, spoke Urdu. By implication, real Hindus of respectable moral character did not use Urdu.”

Thus Hindi got associated with Hindus and Urdu was left for Muslims. And by 1934, when Munger administration was ready to rebuild the city, they chose to establish two libraries, one for each language. And when Nawal Kishore along with his accomplices robbed the Urdu Library in 2015, he probably didn’t think much of the books collected there, it was a language of the “others” – a legacy of hate that started about 150 years ago.

The same legacy that has given rise to Hindutva leader Narendra Modi, who closes the circle by giving a copy of the Persian book of history written by Jewish convert to Islam on the order of the King, who was a Christian-convert of Islam. Incidentally, the book was brought to India by Muslim invaders and preserved in a library established by Nawabs, who supported British during the 1857 War of Independence, a war that Indian forces lost and British established the “divide and rule” policy to keep Hindus and Muslims apart. A result of which was creation of Pakistan and, later, destruction of Babri Masjid amid violence on religious lines killing millions and giving rise to Hindutva ideology which has made Modi the Prime Minister of India.

But I prefer that we end this article with the view of writer Ratneshwar Prasad Salik who Ahmad quotes in his paper: “We have both together created a new language – the Urdu language – which was neither our language nor theirs. Urdu is the strongest foundation and the biggest symbol of the national unity. May this language live, so we both live!”

——–

(Kashif-ul-Huda, a Muslim, was educated in a Hindi-medium school run by Christian missionaries.)