By Misbahuddin Mirza for TwoCircles.net

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s (the Met, New York) fabulous exhibition – Power and Piety: Islamic Talismans on the Battlefield (Aug 29, 2016 thru Feb 13, 2017), discusses a fascinating aspect of Islamic Art. According to Dr. Maryam Ekhtiar, Associate Curator, Department of Islamic Art, and Dr. Rachel Parikh, Mellon Curatorial Fellow, Department of Arts and Armor, organizers of this exhibition, ‘Inscriptions and images on Islamic arms and armor were believed to provide their wearers with safety and success in combat.

This exhibition, featuring some 30 works from The Met collection, examine the role of text and image in the construction and function of arms and armor in the Islamic world. Qur’anic verses; prayers that invoke Allah, the Asma al-Husna (99 Beautiful Names of Allah), as well as the Prophet Muhammad, his family, and companions; and mystical symbols were all used to imbue military apparel, weapons, and paraphernalia with protective powers.’

“Stamp Seal Iran, early 18th century Silver, cast and engraved The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Edith Aggiman, 1982 (1983.135.11) Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The punctured stem of this stamp seal suggests that it may have been worn as a pendant. The star includes the names of the Rashidun (“Rightly Guided”) caliphs and the Prophet Muhammad.”

Dr. Ekhtiar and Dr. Parikh answered my questions, explaining that the use of Talismans was quite widespread (in the geographic regions covered by this exhibition). I pointed out that the Sahabas of Prophet Mohammed (PBUH) did not use Talismans and asked if the use of Talismans was limited to non-Arab armies. Dr. Ekhtiar stated “I believe that non-Arab armies used Talismans but non-Arab warriors in service of Arab armies probably used Islamic talismans as well……” Dr. Ekhtiar did her PhD in Later Persian Paintings from New York University and is a specialist in the field of later Persian art and culture, and has particular expertise in calligraphy. Dr. Parikh did her PhD in Indo-Persian painting; she specializes in Mughal and Deccan Sultanate paintings, and is currently preparing her PhD dissertation into a publication. Dr. Ekhtiar said that her next exhibition will probably be about “Later Islamic Calligraphy.”

However, the introduction of these practices on the battlefield was not always quite in line with Islamic teachings. While some of the practices described in this Exhibition could fall in the category of normal and acceptable daily practices – such as taking the Qur’an (final section of the Met’s Exhibition) along for recitation during non-combat times, hanging verses of the Qur’an as a reminder of important Divine instructions, etc. (comparative/ applicable Fatwa: Shaykh Muhammad ibn Saalih al-‘Uthaymeen , al-Bida’ wa’l-Muhdathaat wa maa laa aslun lahu, p. 259; but, some other practices, discussed later in this article, could be classified as Shirk – a major sin under Islamic law.

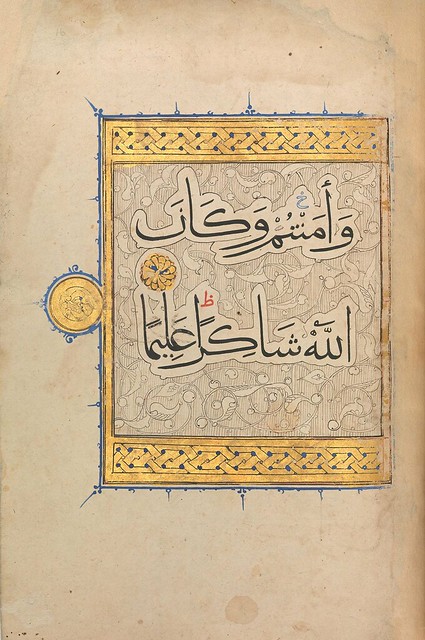

“Section from a Qur’an (4:114–147, of the Women) Egypt, probably Cairo, ca. 1320 Ink, opaque watercolor and gold on parchment Binding: Leather; tooled The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Gift of Newton Foster, and funds from various donors, 2006 (2006.212) Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.”

The exhibition has been organized into five thematic sections. The first establishes the context for understanding the empowering inscriptions and symbols that can be found on Islamic arms and armor. It examines a variety of textual and iconographic sources, such as the Qur’an, prayer books, and votive tablets (Hilya).

The next three sections of the exhibition, have a geographical focus, and show objects from Iran, Turkey, India, and Southeast Asia. The works include armor (helmets, mail shirts, and cuirasses); weapons (daggers and sabers); and paraphernalia (banners and standards).

Talismans from India’s Shi’i Deccan Sultanates such as helmets, swords, and Persian talismans are also on display. It was believed that the strategic placement of inscriptions and symbols— protected a soldier’s most vulnerable and vital parts. For example, the inscription of the name “‘Ali” on the nasal guard of a helmet from India was intended to bring added protection to the wearer’s face. However, the practice of beseeching the help of deceased humans – be they anyone, including Rashidun Khailfas, or deceased saints has been ruled as un-Islamic, by mainstream Muslim scholars, explaining that it constitutes as Shirk – i.e. associating a partner with Almighty Allah (Majmoo’ Fataawa al-Shaykh Ibn Baaz 2/453; Fataawa al-Shaykh Ibn ‘Uthaymeen, 2/133; Dar ul Ifta, Darul Uloom Deoband, Question 1603)

At the heart of almost all Talismans are indecipherable, incomprehensible, letters, numbers and figures; these are usually from magic books – which are unequivocally prohibited in Islam. In order to lure gullible Muslims, some Islamic terminology is added in a prominent location, in very legible font; this serves two objectives – firstly, it gives an aura of religious authenticity to an un-Islamic article, and secondly it attempts to convince the lay Muslims to treasure the talisman in a safe place rather than getting rid of it, for fear of committing a sacrilegious act.

Analyzing a talisman: Now, let us analyze the above Iranian Stamp Seal talisman. The smaller inner area is used for clearly writing the name of the Holy Prophet and the four Rashidun Khalifas. To the lay Muslim, this portion is easy to read and then assume that the rest of the unreadable portion in the majority area of the seal may be a verse from the Qur’an. Try holding this seal’s photo in front of a mirror and see if you can read the words in the larger outer ring. Don’t blame yourself if you were unable to read it. That’s the whole point of a Talisman- i.e., to create smoke and mirrors. Let’s look at this a little bit more closely. First, Surah Kahf of the Qur’an does not confirm that there were “seven sleepers” – it simply states existing different beliefs prevalent among people at that time – that some say there were three sleepers, others say there were five sleepers, and yet others who say that there were seven – thus eliminating meaningless details/ discussions, and bringing the Qur’an’s reader back to the real essence of the story at hand. Second, the Qur’an absolutely does not provide the names of “the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus and their dog,” at all. So, where did this talisman preparer then get the names of these “Seven Sleepers” from? The Bible can be ruled out, as this story is not mentioned in the Bible. But, some Christian traditions tell this story in Greek by a Symeon Metaphrastes in his ‘Lives of the Saints,’ giving the names of the “seven sleepers,” as ‘Maximilian, Iamblicus, Martinian, John, Dionysius, Exacustodianus, and Antonio.’ If the names mentioned on the seal are the same names as those mentioned by Metaphrastes, then this is a Christian talisman with a Muslim facade. Further, Surah Kahf, Ayah 22 specifically instructs Muslims not to consult the people of the Book regarding the story of the people of the cave; therefore, using the names from Metaphrastes’ book would be in defiance of Qur’anic injunctions. Lastly, the presence of geometric shape(s)/ patterns adds another layer of distrust and suspicion that this talisman may have something to do with necromancy/ occult. Therefore, as we see from this discussion, there cannot be anything Islamic about this talisman, save the previously discussed thin veneer of some Islamic terminology.

“Helmet India, Deccan, 17th century Steel, gold, copper alloy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of George C. Stone, 1935 (36.25.63a) Image: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York”

When evaluating a matter, Muslims look for guidance first from the Qur’an, then from the Ahadith (teachings of Holy Prophet). Muslims also look at the Sahabas’ (companions of the Prophet) practice to find out how the Sahabas had dealt with a particular issue, as there is a Hadith stating that the Sahabas are like stars and the Muslims would succeed if they followed any of the Sahabas.

“And who is more astray than one who calls on (invokes) besides Allah, such as will not answer him till the Day of Resurrection, and who are (even) unaware of their calls (invocations) to them?” Qur’an, Surah al-Ahqaf, 46:5

The Prophet said to Ibn ‘Abbaas (RA): “If you ask, then ask of Allah, and if you seek help then seek help from Allah [al-Tirmidhi, 2516, classed as saheeh]

So, let us look at two of the most important battles fought by the Sahaba – the battle of Qadisiyah, and the battle of Yarmouk – where the very survival of the nascent Muslim community was at stake. A handful of scarcely equipped, poorly supplied Sahabas had set out to take on the might of the massive, well equipped, well trained, well supplied Sassanid Persian superpower. As if this seemingly insurmountable challenge was not enough, they had to soon divert resources to also take on the other military superpower – the colossal legions of battle hardened warriors of the mighty Byzantine Roman war machine. When staring down these mighty giants, what did the Muslim Sahabas do? They did not take any talismans along in these battles; instead, they put their faith in Almighty Allah. In turn, Allah rewarded them by making them the sole military superpower of the world. This promise of Allah is depicted in the following Met exhibit, which shows the second half of Ayah 147, Surah 4, which translates as “……..and a true believer, Allah is always responsive to gratitude, all-knowing.”

The author is the Regional Quality Control Engineer for the New York State Department of Transportation’s Structures Division, New York City Region. He has taught at New York and New Jersey’s Sunday Islamic schools, and delivered Friday sermons. He has written for major US and Indian publications.