By Syed Danish, Twocircles.net

Waqar Nasri

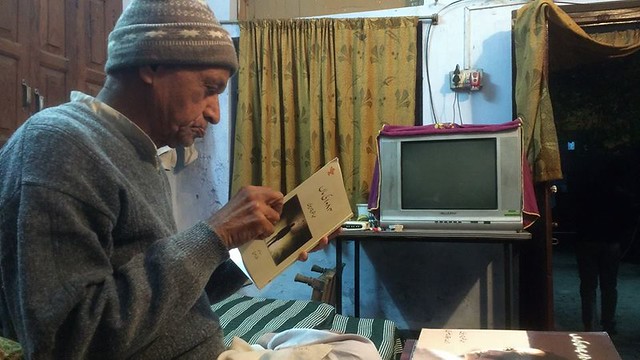

Waqar NasriIn one of the many bylanes of the Sheeshmahal locality in Hussainabad area in Old Lucknow, lives Waqar Nasri or ‘Nawab Alam’ to his near ones. To many in my generation, this name may be like a dot in the statistics records but not to those who have his Urdu translation of ‘Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Ma’ and other volumes of works he has published as a literary critic and translator.

Sitting on an armchair in the courtyard of his ancestral house, the 75-year-old litterateur diligently turns the pages of his translated books. His demeanor is calm and unassuming. He is one of the few remaining doyens of the Urdu world of his fast dwindling generation which has gracefully defended the citadel of their language and preserved the awe and integrity of the culture of adab in Lucknow.

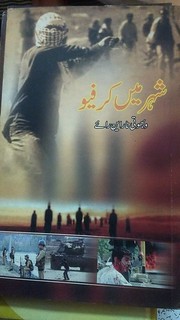

He is currently translating a Bengali novel titled ‘Shahzada dara Shikoh’. In the past, he has written essays on ‘Aag Ka dariya’, ‘Aakhri Shab Ke Humsafar’ by Qurratulain Haider; ‘Gulaalbagh’ by Mirza Athar Beg, and other novels like ‘Darichey’, ‘Khiza ke Dinon Mein’. He has also written poetic commentaries titled ‘Peshkhema’ and ‘Shahr Meer’, the latter on Nasir Kazmi’s poetry. He has also translated book on Birsa Munda titled ‘Jungle Ke Daavedaar’ and Vibhuti Narain Rai’s ‘Shaher Mein Curfew’. He has also translated into Urdu various jail diaries such as ‘Hum Jo Maare Jaayenge’ by Jiya Mitra.

“Logon ko maloom hi nahin hai ki iska tarjuma hua hai, (People have no idea this novel has been translated in Urdu also),” he says referring to the disassociation of the younger generation at large with Urdu. It is his reputation in the Urdu world which earned him the Sahitya Akademy offer to translate one of the greatest works of Mahasweta Devi, who is known for bringing the pain and trials of the common man on world stage through the might of her pen. His translated book was published in April this year.

Nasri heaps volumes of praises for Hazaar Chaurasi ki Ma since he has read the Hindi translation of the original Bengali novel. He says, “In Hazaar Chaurasi Ki Ma, she addresses an entire generation engulfed in political turmoil of their age. A generation lived on the morsel of their dreams of a just and an egalitarian society before fate got the better of them. In the novel, Brati’s character epitomises the vision of an ideal society – the destitute would rule one day. His father challenges and sometimes mock his perception and argue in favour of materialism.

Sujata, his mother on the other hand, is a wife of a wealthy husband who is accustomed to a smooth and comfortable life. So when Brati explains her the concept of class struggle and Naxalbari movement, it leaves her worried and perplexed. But, unlike her husband, she listens to and understand him. This is the binary of the mother-son relationship which is the soul of the book,” he says with an emotional glint in his eyes.

If you want to know the true nature of women, read this book,” he emphasises. Nasri believes that in many pages of the book Sujata exhibits the same kind of courage and resilience that Mahasweta Devi did in her own life while speaking to the marginalised in the country. She doesn’t call it quits even after watching her son’s body in the police station but heralds on towards a journey to explore the part of his life she wasn’t familiar with in order to stand by him. This is her expression of faith in the purity of her son’s ideas.”

Even the tag reading 1084 on Brati’s body, according to Nasri, is Mahasweta Devi’s way to tell how, in the books of a repressive State, an idea is reduced to a number.

Before working on his translation, Nasri visited Kolkata to understand the city better. “The novel is set in Kolkata so I visited the city and its by-lanes to get a picture of where Brati lived and dreamt of a new world with his comrades and travelled so far in his quest that the difference between reality and his dreams became non existent.” He also met Urdu writers like Zaheer Anwar who helped him get acquainted with Kolkata of Mahasweta Devi’s novel.

To the young breed translators, Nasri has to say that translation a delicate and responsible job and the essence of the original work must not be lost in translation. He also cites the example of Sujata and her maid. “Both Sujata and her maid speak Bengali but in different ways. For instance, Sujata’s Bengali is refined where as maid’s has a rural touch. So while translating in Urdu I had to be sure that the line so maid did not have to be nafees or refined. So you see, that when you are translating a novel, it also the background of the characters that you put into the right context in the framework of your translated text.”

Nasri laments the demise of Mahasweta Devi and believes that the world needed her more than ever. What moved him the most about her is that she worked and boisterously voiced her concerns in the interest of the downtrodden. “She was the editor of ‘Vartika’ magazine which published writings of adivasis and tribals. She also wrote for children which shows that she issues of all age groups would affect and touch her sensibilities.”