Cleaning India, but dying a slow death: How manual scavengers pay with their lives

By Raqib Hameed Naik, TwoCircles.net

Ghaziabad (UP): It is a busy but regular weekday in Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh. At the tea point in Sector 10, Titu, 26, takes off his clothes as he readies himself to enter a manhole leading to a sewer containing human excreta, slush, and plastic. A resident of Bhadouli village in Ghaziabad, Titu is a sanitation worker for the Ghaziabad Nagar Nigam since the last ten years. He first entered into a sewer to clean when he was just fifteen years old.

[caption id="attachment_418122" align="aligncenter" width="2460"] Titu, 25 wakes up at 4 in the morning to clean the sewers in different sectors of Rajnagar, Ghaziabad. (Photo: Raqib Hameed Naik)[/caption]

Titu, 25 wakes up at 4 in the morning to clean the sewers in different sectors of Rajnagar, Ghaziabad. (Photo: Raqib Hameed Naik)[/caption]

As he takes off his clothes, the injury marks and skin lumps are clearly visible across his body as a result of infections caused by the cleaning of sewers and septic tanks. With a rope strapped to his body, he enters the sewer with a bucket to manually clean it.

“Some of the sewers have not been opened for years altogether, which leads to the formation of toxic gases,” Titu says. And in recent times, these toxic gases have sounded the death knell for sanitation workers. Since August this year, more than 12 people have died due to asphyxiation while cleaning sewers, septic tanks and drains across Delhi. The deaths have brought back into focus the practice of manual scavenging and dangers associated with it. However, a lot less space in media has been allotted to the health-related issues which the workers have to live with rest of their lives.

“During early years of my work, I was doing fine, but slowly I started developing skin infections and respiratory problems. Lately, I have been suffering from digestive problems and doctor has told me that my work is the cause behind it because the filth inside the sewers enters our mouth and makes its way inside the body,” says Titu.

Manual Scavenging, a centuries-old practice in India, continues unabated across India despite the country banning employment of people as manual scavengers in 1993. In 2013, the landmark ‘Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act’ was passed, which came into force in February 2014. The act seeks to reinforce this ban by prohibiting manual scavenging in all forms and ensures the rehabilitation of manual scavengers to be identified through a mandatory survey.

According to the 2011 census, there are more than 2.6 million dry latrines in the country besides there are 13,14,652 toilets where human excreta is flushed in open drains, 7,94,390 dry latrines where the human excreta is cleaned manually. So, the practice of manually cleaning, carrying, disposing and handling of human excreta from dry latrines and sewers continues unabated. And it does not take rocket science to figure that in a deeply-casteist society like ours, all manual scavengers belong to the Dalit communities.

“No one wants to enter in filth but at the end of the day we have to feed our families and feeding considerations overtake all other consideration despite knowing that there are very serious health issues related to it,” says Suresh, a 52-year old manual scavenger.

Suresh was 25-year-old when he started working as a manual scavenger to feed his family of five. During early years of his work, he developed respiratory tract problems. “The gases inside can kill you in seconds. In 2012, a sewer near Ghaziabad railway Fatak was opened for cleaning after many years. The manhole lid was kept open for three days so as to clear sewer from toxic gases,” he recalls.

After three days, when Suresh entered the manhole, the toxic gases were still present inside and he started suffocating. The alertness of the fellow worker, who was at the end of the rope attached to his body saved him as he was pulled out timely.

[caption id="attachment_418123" align="alignnone" width="2256"] Suresh, 52 showing his injured arm while cleaning a sewer. (Photo: Raqib Hameed Naik)[/caption]

Suresh, 52 showing his injured arm while cleaning a sewer. (Photo: Raqib Hameed Naik)[/caption]

Suresh has developed various medical complications over the years. “I was first diagnosed with Tuberculosis followed by herpes in 2013. In 2015, doctors told me that the condition of my lungs had deteriorated extensively even though I don’t smoke. Now sometimes, I vomit blood,” he added.

Suresh has been put on medication by doctors and has been advised to use asthma inhaler in case of breathlessness. He has spent lakhs of rupees on his treatment, taking loans from his friends and relatives but lately, he has stopped visiting the doctors.

“You can’t take leave at work every day. You can’t you spend money on medicines and consultations when you are paid Rs 7,500 a month,” he said.

Inside the sewers, the workers are exposed to gases like hydrogen disulfide, methane, ammonia, and carbon monoxide. Studies have confirmed that these gases lead to cardiovascular degeneration, musculoskeletal disorders like osteoarthritic changes and intervertebral disc herniation, infections like hepatitis, leptospirosis, and helicobacter, skin problems, respiratory system problems and altered pulmonary function parameters.

What is clearly evident while talking to the workers that years of service does nothing to change their lives. Take the example of Deep Chand who is 53 years old. He was 27 when he joined Ghaziabad Municipal Corporation and has been working for it since then, cleaning sewers. He has been a witness to the death of his co-worker in 2010.

“In 2010 one of my co-worker, Ravi died in front of me inside the sewer. He couldn’t even shout louder so that we could pull him out of the manhole.”

During his 25 years of work, Malkan had several trysts with his life while cleaning the sewers but he feels that he is long dead.

“I have spinal disc problems due to pulling up of buckets with ropes from the sewers. My lungs are bad. My night starts and ends with a cough. Sometimes, I can’t breathe and have to use an asthma inhaler. It is better than to die there in sewers,” he said.

Malkan has to visit a doctor at Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital in New Delhi every fortnight and spends half his monthly income on medication.

“We don’t have that much income that we can get ourselves treated at private hospitals and clinics. So we end up at a government hospital where we have to wait for months to see a doctor,” says Malkan.

Malkan had visited a government hospital last month and was advised to go through Electrocardiography and he has been given appointment of October 2018.

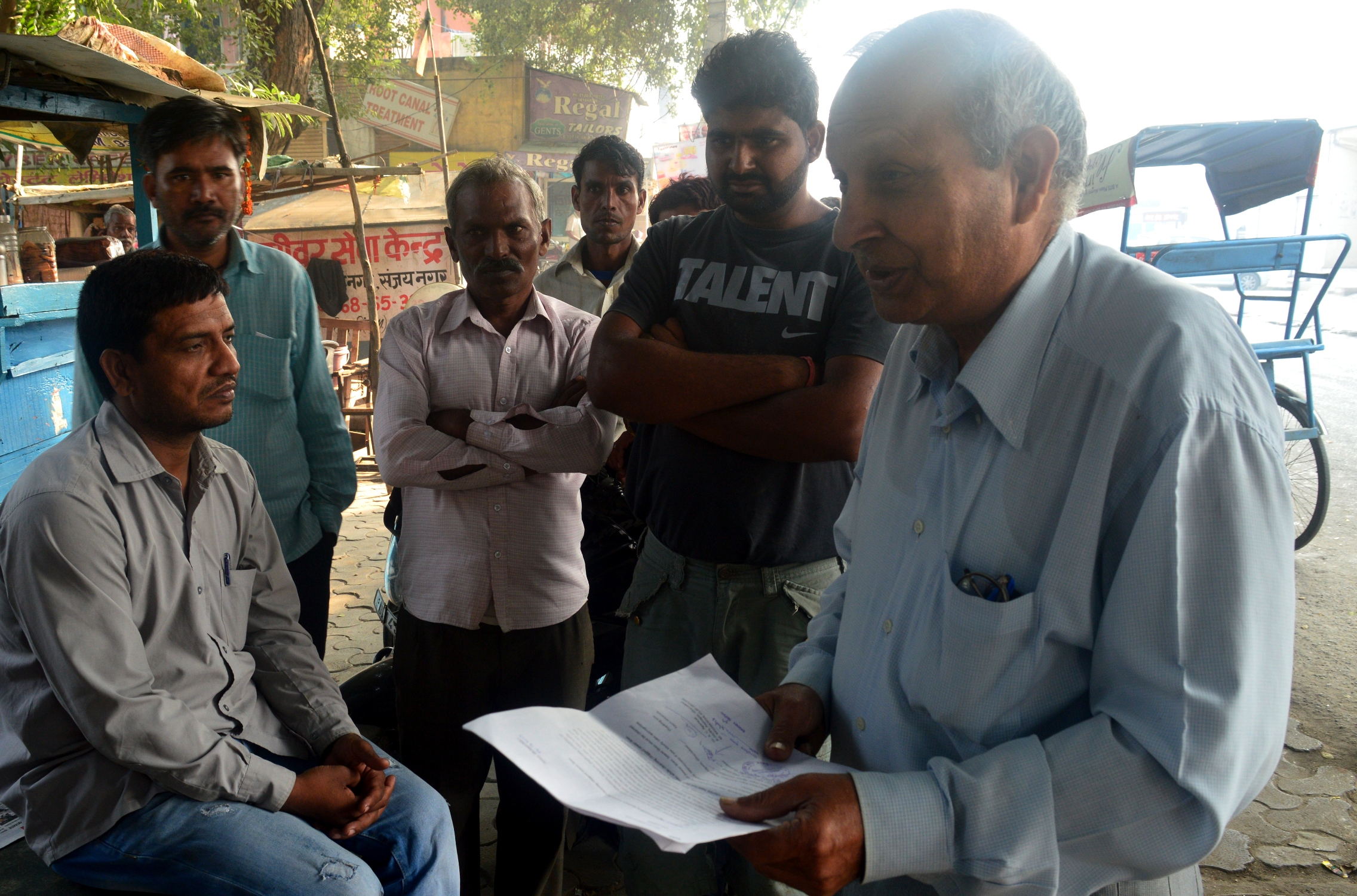

According to Dr. R.C Agarwal, a retired academician who organizes awareness programmes for sanitation workers apprising them about the health issues related to their work, every worker is at grave risk of developing serious health complications and mortality rate among manual scavengers is quite high and the government should look towards their rehabilitation.

[caption id="attachment_418124" align="alignnone" width="2272"] Dr. R.C. Agarwal creating awareness among the manual scavengers about the health issues associated with their work. (Photo: Raqib Hameed Naik)[/caption]

Dr. R.C. Agarwal creating awareness among the manual scavengers about the health issues associated with their work. (Photo: Raqib Hameed Naik)[/caption]

“These sanitary workers get down in sewer manholes full of human excreta, toxic waste, blades, needles and even contain snakes, to clean clogged sewer lines. They are exposed to serious health hazards. Their skin and genital parts such as anus, penis etc are exposed to dangerous harmful toxic waste. They often catch diseases at a very early age and don’t live long.”

Dheeraj Kumar, 25, knows the health hazards associated with his work and has seen his fellow workers getting bedridden. Yet he chooses to sideline all the consequences.

“I am not educated and can’t get a good job. Even if I apply somewhere, they won’t hire me if I tell them I used to clean sewers manually,” he says.

“I know I will not live long due to my work but for the time being, it is the only source providing my family with two square meals,” he adds.