Caught between two extremes: Views of Sir Syed on gender, caste and nationalism

By Mohammad Sajjad for TwoCircles.net

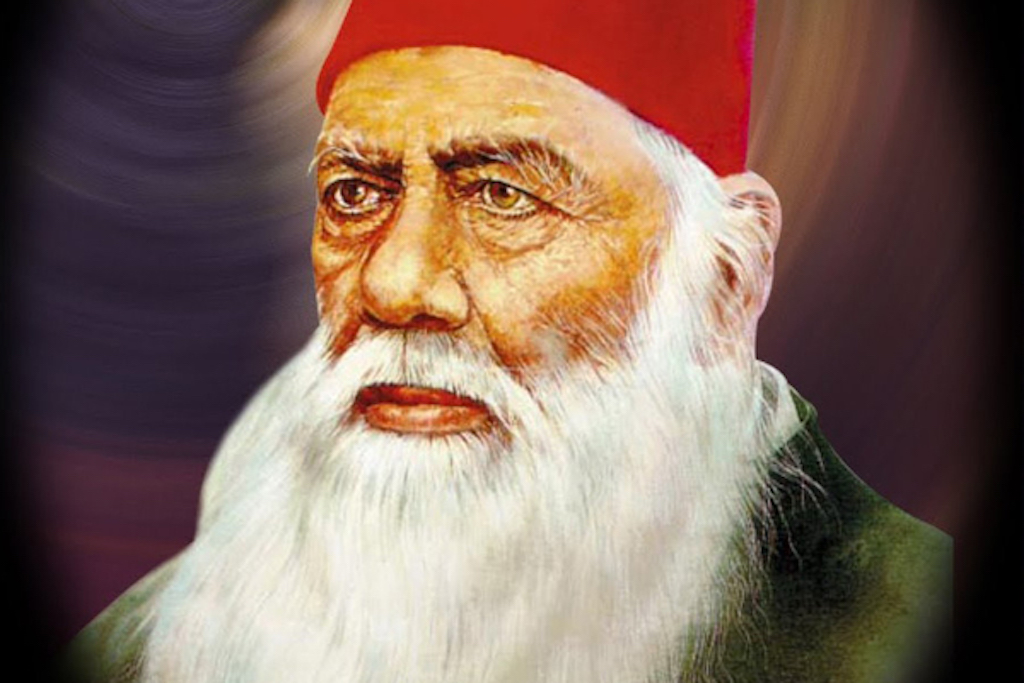

As the birth bi-centenary of the distinguished reformer-educationist, Syed Ahmad (1817-98), a realist-pragmatist of 19th century India, and founder of the MAO College (later Aligarh Muslim University) is being celebrated, one finds the interpretations of his words and deeds caught between two extremes: deification and disproportionate blaming, particularly on the issues of caste, gender and nationalism.

Till 1859, Sir Syed was hardly concerned with reformism. His intellectual pursuits were confined to studying India’s past, howsoever with adequate scientific rigours, and also to intra-Islamic sectarian debates. Yet, he preferred to edit (1855), among other works, the Ain-e-Akbari, rather than something on Aurangzeb, a monarch much maligned by various groups as a bigot ruler. In pre-1857 period, he does not seem to have believed as firmly in the permanence of British rule. So much so that when he went to Ghalib (1797-1869) asking him to write a foreword (taqriz) for the Abul Fazl’s Ain-e-Akbari he had edited, Ghalib reprimanded him, asked him to look up to the West, and its accomplishment, instead of wasting his time and talent on dead things of past. Such a suggestion, at that time, was unpleasant for Sir Syed who did not include the versified foreword that Ghalib wrote, admiring material and intellectual advancements of the West.

From 1859 onwards, his sole concern was to regain the lost (and safeguard the existing) share of his Qaum in the evolving structures and processes of power. Historically subordinated groups were not there in his scheme of things. While analysing the causes of the violent upsurge of 1857, he not only tried to absolve the upper strata of Muslims but also tried to put some blame on the historically oppressed communities of Muslims. His prejudices against such groups would re-appear in 1887, when he would oppose political stand espoused by the Indian National Congress.

In his diagnosis, fulfilment of such an objective needed educational uplift. He was absolutely clear-headed about this, and only consistent thing in his words and deeds was this. For this to actualise, he kept changing his strategies, as frequently as was needed because of colonial education and employment policies. He diluted stridency on interpreting Quran, just to avoid the attacks of the clergy; advocated Anglo-Muslim rapprochement, and dissuaded the Qaum from joining anti-establishment politics, was all geared towards it.

Through his very extensive study of Indian past, ancient and medieval, he derived a conclusion that the foreign rulers had come down to India only to settle down, just as the Mughals, Lodis, Sultans, Indo-Greek dynasties, and even much earlier, the Aryans, had done. Hence persuaded his Qaum to come to terms with it and negotiate with it (not only politically but also culturally), rather than confronting it to get crushed by the technologically, intellectually and materially.

Sir Syed may be said to have got some inkling of the times to come, evident by the fact that while choosing for a job, he preferred to join the Company administration in 1837-38, instead of the Mughals.

That his reformism---obtaining education for employment--- was unconcerned for the lower Muslims may also be evaluated by taking into account a fact that in November 1859, when he started a school at Moradabad, he made a breakthrough by asking the relevant class of Hindus and Muslims to discontinue the practice of domiciliary education and take recourse to public schools. This was a big step for the age asking all to sit together in a school classroom. Similarly, when he debated a Report on Muslim education (1872), he strongly disagreed with those who talked of excluding the “low born” from the proposed college. He made an elaborate argument, that, the rule of law and notion of justice, disapproved such social exclusion. He further argued that if the elites and masses all could travel together in lower class of rail-bogey, just to economise the travel expenses, shunning the snobbery, why and how they should practice this social exclusion in government-aided educational institutions. Moreover, he may not have spoken against caste-ism practised in Islam, but he did not prohibit enrolment of “low born” to his M. A. O. College. Instead, proportion of the “under-class” enrolments kept rising. Sir Syed insisted on instituting fellowship endowments to educate the poor. Syed Mahmud’s Dar-ul-Ulum (independent university) scheme also talked of such charitable endowments.

Today, politically it is quite valid and useful to raise question against evident elitism of Sir Syed. Equally valid and useful however would be to understand that given the ethos of 19th century, Sir Syed’s efforts to mobilize fund for his educational enterprise must have crumbled, had he raised issues of, what we now call, social justice. He was already embattled severely with the clergy which was hell bent upon keeping Muslims away from modern education.

On the question of ‘nationalism’, Sir Syed’s opposition to the Congress is taken as a proof to indict him. His advice to shun politics and concentrate on modern education was there for both Muslims and Hindus. During 1862-85, his words and deeds were strongly for Hindu-Muslim unity. His advocacy of vernacular (Urdu) education met with a strong resistance from the votaries of Nagri, in late 1860s. These men included his friends like Raja Shiv Prasad. Those were the decades of growing communalization with evident colonial prodding to the Nagri protagonists, mainly by Kempson in what is now UP, and by Campbell (1871-74) in Bihar. This embittered Sir Syed. The Benaras Commissioner, Shakespeare, noticed this in 1867. Yet, communally divisive utterances were not there. What remained there, was, particularistic concerns for one’s own community. This communitarian particularism was not the differentia specifica of Sir Syed alone. It was there with all the reformers of the 19th century.

His essentially pragmatic approach made consistency impossible to achieve.

During 1862-1882, Syed Ahmad’s views showed pro-Indian sentiments. During 1882-1884, he professed to speak for both Hindus and Muslims fundamentally in accordance with the principles upon which the Indian National Congress (INC) was founded in 1885. The Pan Islamism of Jamaluddin Afghani (1838-97), advocated that the Ummah (Muslims across the globe) should stand united to oppose British imperialism, and it also appreciated the Caliphate. Sir Syed opposed it that extra-territorial, supra-national, loyalty with caliphate at Turkey was untenable. “Attachment to the Khilafat precluded Hindu-Muslim cooperation and the development of true nationalism among Indian Muslims. Syed Ahmad‘s determined stand on this point would appear to be directed at opening the way for Hindu-Muslim cooperation, as much as to weaken the hold of the conservative Muslim leaders on the Muslim community”, underlined Denis Wright (1989).

He gave premium to Qaum for whom he had undertaken an extensive programme of educational, cultural and political reform. His objections to the authority of the Khilafat, however, leave no doubt that ‘Qaum’ referred to the Muslims of India alone. Qaum or nationality to him meant not necessarily India’s Muslims alone, as it referred also to Hindus, and to caste among Hindus, or regional groups (Bengalis). Contextually, in his usage, essentially speaking, Qaum referred mostly to the Indian Muslims. In his Gurudaspur speech (1883-84) he said, “I have used the word “nation” several times ... By this I do not mean Muslims only. In my opinion all men are one and I do not like religion, community or group to be identified with a nation”.

During 1885-1888, he spoke as a Muslim leader of north India and as an opponent of the INC; and during 1889-98, he left the public political arena, and kept persuading his Qaum even more to shun politics and concentrate on modern education. His drive for fund to raise his M A O College became more strident. Nehru, in his Discovery of India (1946: 375-85) argued that Sir Syed opposed the Congress for its radicalism and he advised Hindus also to stay away from it. Nehru attributed such response to late formation of modern middle class among Muslims---metaphorically a gap six decades (Brahmos’ Hindu College, Calcutta founded in 1817 and MAO College, Aligarh in 1877).

On his suggestion in his tract on the causes of 1857, when the Imperial Legislative Council came into being and three Indians were inducted into the Council, they were all Hindus, viz., Maharaja of Patiala, Raja of Benaras, and Dinkar Rao. Sir Syed welcomed it, without complaining as to why no Muslim was there in it.

Notwithstanding his loyalty to the British, more than once, he and his son, protested against racial arrogance of the British. It is Jinnah’s biographer (1954), Hector Bolitho, and US-based Pakistani academic, Hafeez Malik, in desperation to find antiquity for exclusionary nationalism of Pakistan, traced roots of India’s partition in Sir Syed, and it later gained currency among the Hindu communalists. Sections of nationalist historiography, despite adequate explanation by Nehru, only reinforced such misleading attributes. Surprisingly, the scholar of nationalism, like, Partha Chatterjee, discussing first phase of evolving nationalism in India---“the moment of departure”--- appreciated Bankim (1838-94), despite his pro-British and anti-Muslim storyline in Anandmath(1882). He credited Bankim’s literary outpourings to have contributed to the rise of nationalism through his articulation of India’s superiority/autonomy in spiritual domain. The same yardstick is not applied to the Muslim ‘fragment’ of the Indian nation. Sir Syed and his companions created far more progressive and voluminous literature in Urdu which decisively went on to serve as intellectual resources against the British colonial hegemony. With the turn of the century, the MAO College did become a nerve-centre of anti-British agitations. The campus, just as the rest of the society, bustled with all political trends: nationalists, leftists and dissidents. The first graduate and postgraduate of the college were Hindus, first three principals were British Christians, and first chancellor of the University was a woman. Beef remained banned in the hostel, and scholarships specifically for Hindu students, were also there.

Syed is also blamed for opposing women education. In one of his speeches he was indeed harsh on this. He said, India may have to wait for hundreds of years when it would be able to afford opening women’s colleges.

Later, he argued that he should not be misunderstood on the issue. His pragmatism about letting the agenda wait till more resources and more receptive and enabling environment come about, is often glossed over, by the scholars and commentators. His articles in the Aligarh Institute Gazette (AIG) and his travelogue of London wouldn’t satisfy today’s “feminists”, but these are not to be ignored completely. The travelogue records Sir Syed’s admiration for a maid-servant Naseeban, of Kanpur, on board the ship for 21st trip to Europe, who could speak English. Syeds showered laurels upon the maid-servants of London who unfailingly took time out to read newspapers every day. He wished India should reach this stage soon. He editorialised his praises in the AIG (September 1883) for the scholar-reformer, Pandita Ramabai (1858-1922), with whose efforts medical education and training to women made significant progress, and Kadambini Ganguly (1861-1923), the first medical graduate to have gone abroad for education. So was the case with Anandi Gopal Joshi (1865-87), the first female physician. Sir Syed particularly appreciatedRamabai’s depositions before the Hunter education Commission (1882) for being helpful in promoting Lady Dufferin’s efforts towards medical education and healthcare to women in India. Just eight years after the death of Sir Syed, his companions, mainly Sheikh Abdullah (1874-1965), did open girls’ college.

To sum up, the reforming intelligentsia of 19th century colonial India had its many limitations. It is politically useful to talk about those. Fanatic ways of admiring or denigrating/belittling such contributions would serve absolutely no purpose.

Prof. Mohammad Sajjad is with the Centre of Advanced Study in History, Aligarh Muslim University.

He has published two books: Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours (Routledge, 2014)

Contesting Colonialism & Separatism: Muslims of Muzaffarpur since 1857 (Primus, 2014)