Devoid of work, artists of Kathputli colony in Delhi turn to odd labour jobs

As part of India's first in-situ slum redevelopment project in a public-private partnership, Kathputli Colony in Shadipur, Delhi, is being developed as a mall and a set of luxury flats. The colony's residents, who are Kathputli artists, consented to be a part of the redevelopment deal after a hard struggle. In this TCN Ground Report, we look at the impact of Covid-19 on these artists, many of whom are now taking to labour work.

Shadab Farooq | TwoCircles.net

NEW DELHI – “People used to perceive us as artists, but once our homes were demolished, they began to see us as poor, and now, amid the Covid-19 pandemic, they see us as beggars,” fifty-year-old Rehman Shah, a traditional magician from Kathputli Colony, currently residing in a transit camp at Anand Parbat in West Delhi, told TwoCircles.net.

[caption id="attachment_442794" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Rehman Shah, 50, Chief Artist and street magician of over 34 folk artist families. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Rehman Shah, 50, Chief Artist and street magician of over 34 folk artist families. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Rehman Shah said that “with both comic speech and sleight of hand, street magic used to be a matter of attracting an audience and holding their attention.”

Shah said that nobody wants to see street magicians up close these days “because of the fear that coronavirus has created and the social distancing rules.”

[caption id="attachment_442795" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Rehman Shah is an internationally acclaimed artist and has performed in several countries with his team. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Rehman Shah is an internationally acclaimed artist and has performed in several countries with his team. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

As part of India's first in-situ slum redevelopment project in a public-private partnership, Kathputli Colony in Shadipur, Delhi, is being developed as a mall and a set of luxury flats. The colony's residents consented to be a part of the redevelopment deal after a hard struggle.

People living in a makeshift camp near Anand Parbat in West Delhi are awaiting their turn to be housed. The makeshift camp is a temporary home of the capital's best traditional puppet artists, magicians, acrobats, and musicians.

Rehman Shah, who has represented India in several countries, has decided to leave the colony and end his long wait for a home.

[caption id="attachment_442796" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] An overview of the Transit camp of these artists at Anand Parbat, in West Delhi. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

An overview of the Transit camp of these artists at Anand Parbat, in West Delhi. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

“It's pointless to wait if the authorities are unable to provide you with basic necessities like water and food. We are not permitted to perform on the streets. We do not have access to one-time food. How will we survive if they won't let us work?,” asks Shah. “It is preferable to depart from here then to perish,” he added.

[caption id="attachment_442797" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Makhan Bhat, 35, a puppeteer in Anand Parbat, wearing a giant puppet head. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Makhan Bhat, 35, a puppeteer in Anand Parbat, wearing a giant puppet head. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Lucky Bhat, 32, a puppetry artist from the Kathputli Colony, currently residing in Anand Parbat, is doing daily wage work to support and feed his family during these difficult times. Lucky is the son of Sangeet Natak Akademi Puraskar winner Pooran Bhat.

[caption id="attachment_442798" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Lucky Bhat, 32, practicing before his live online performance. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Lucky Bhat, 32, practicing before his live online performance. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

“My father and I perform internet shows. It isn't enough to cover our expenses,” Lucky Bhat said. "A small Facebook page's viewership is different from what we're used to seeing. I began doing labour work because I was hopeful that at the end of the day, I would have 150 rupees in my pocket.”

[caption id="attachment_442799" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Lucky Bhat performing puppetry during an online show. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Lucky Bhat performing puppetry during an online show. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

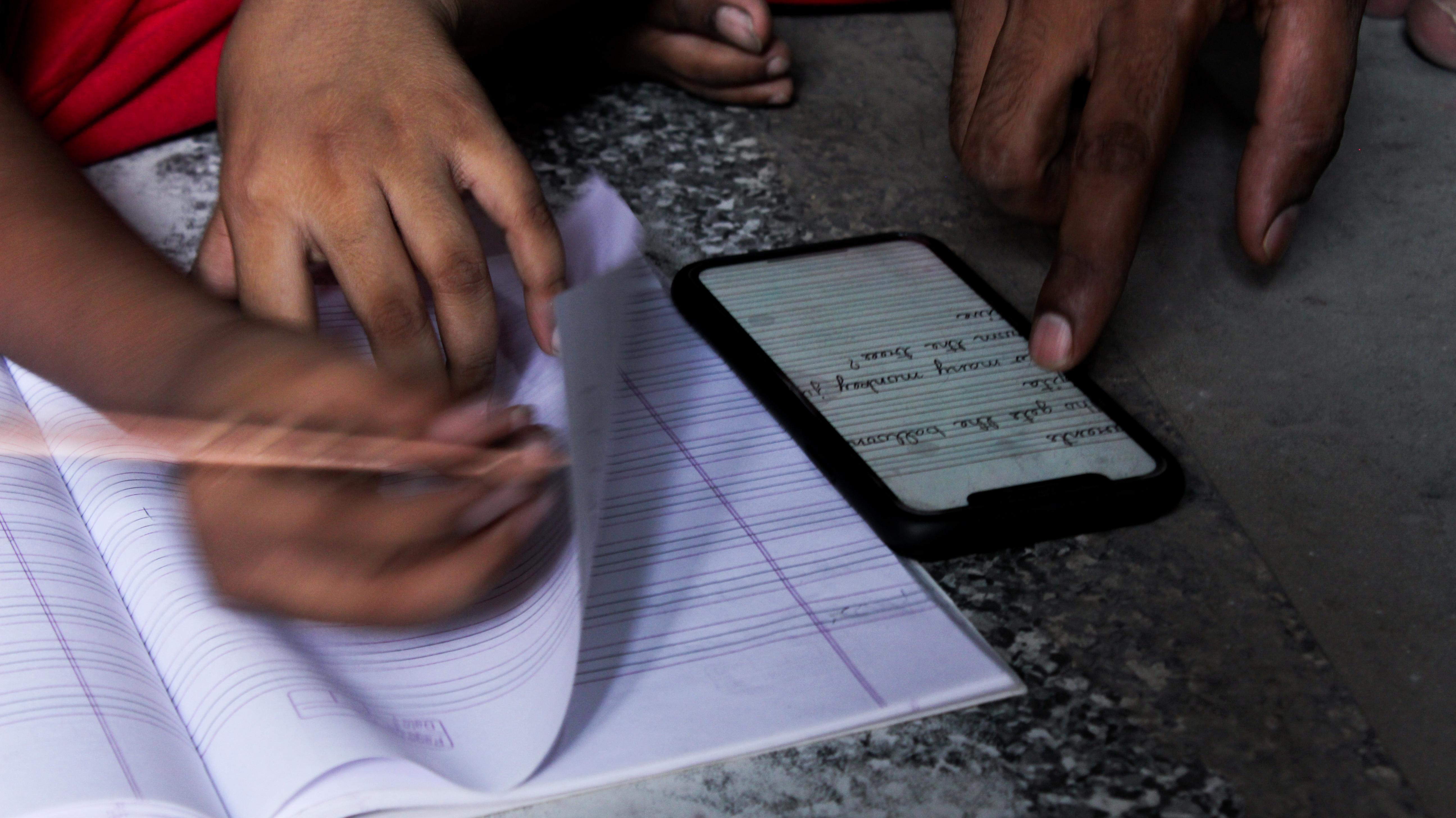

Before the Covid-19 outbreak, Lucky moved his son, Niketan Bhat, 4, from a government school to Happy Senior School, a private school in Kirti Nagar. “I dropped out of school when I was in tenth grade in order to pursue my art full-time. I have realised the penalty of being uneducated in these times. It is important for Niketan to receive the best education possible,” he said.

[caption id="attachment_442800" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Niketan Bhat, four years old, doing homework assignments from his father's (Lucky Bhat) mobile set. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Niketan Bhat, four years old, doing homework assignments from his father's (Lucky Bhat) mobile set. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_442801" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Niketan Bhat, 4, is a young ventriloquist and also a Dhol player. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Niketan Bhat, 4, is a young ventriloquist and also a Dhol player. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Ramesh Bhat, 50, used to design all of the puppets himself when the colony's puppetry artists travelled to other countries for shows. Ramesh Bhat, a designer who has been bedridden for two years due to anaemia and respiratory difficulties, hasn't been able to make a single puppet.

[caption id="attachment_442802" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Kathputli designer Ramesh Bhat, 50, resting in his one room set, at Anand Parbat. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Kathputli designer Ramesh Bhat, 50, resting in his one room set, at Anand Parbat. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Ramesh Bhat's daughter Anju, 20, a puppeteer and mehndi artist, took on the responsibility and began completing home chores through the neighbourhood. "I didn't have any other choice. We used to have two meals a day when I first started performing domestic chores. As the disease spread, others in the neighbourhood began to suspect us, and my madam fired me."

[caption id="attachment_442803" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Anju, 20, a young woman puppeteer and a Mehndi artist. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Anju, 20, a young woman puppeteer and a Mehndi artist. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

As a result of the challenges, Anju's younger brother, Sumit Bhat, 15, went to work in a tobacco factory in the Delhi suburbs. "I used to play the dhol, but I no longer do. It is preferable for me to work just in the factory,” Sumit said, adding, "I am paid Rs. 300, which provides medicines for my father and dinner for my family."

[caption id="attachment_442804" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Sumit Bhat, 15, watching his favourite Indian daily "Tarak Mehta ka ulta Chashma" on TV. Anand Parbat. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Sumit Bhat, 15, watching his favourite Indian daily "Tarak Mehta ka ulta Chashma" on TV. Anand Parbat. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Walking with high hopes through different and difficult chores, when Sumit leaves for the factory in the morning, Anju also leaves the house and roams around the nearby areas with mehndi sticks and asks people to get the mehndi done.

Anju aspires to be a fashion designer and has begun saving for admission to a private design course.

[caption id="attachment_442805" align="aligncenter" width="2560"] Anju applying mehndi on one of her clients' hands in West Delhi. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

Anju applying mehndi on one of her clients' hands in West Delhi. | Photo by Shadab Farooq[/caption]

"On good days, I am able to earn upto 100 rupees but there are days when I get no penny and only pain after the day ends", said Anju.