Matto Ki Saikil highlights everyday gendered, casteist reality of Indian villages

Aatika S., a fellow at TwoCircles.net interviews Pulkit Philip, the screenplay writer of film Matto Ki Saikil

The newly released film, Matto Ki Saikil (2022) directed by M. Gani has been garnering acclaimed reviews for its ethical portrayal of a Dalit man’s life in Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Pulkit Philip who wrote the screenplay and the dialogues, talks more about the one-of-its-kind project.

‘I had started reading and writing stories when I was in 7th standard. Though I lived in a small town, I got the rare privilege to be around progressive people, who had a good sense of why and how injustices are happening in our society. So, because of this only, I moved towards filmmaking–and not just stories, but stories which in some way or the other, refer to progressive ideas’, says Pulkit during a conversation.

A student of SRFTI, Kolkata Pulkit hails from Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. ‘I belong to a lower middle-class family. They were completely against films and filmmaking. And financial instability was a constant force. Till the 12th standard, we didn't have an inverter in our home. I remember the nights when I would read novels and write stories with a candle beside me. I remember the smell of the black smoke. Days passed like this, and after much conflict, my family gave up. They agreed to have me admitted to a film school, and luckily, I got the chance too. In film school, I developed as a person and as a cinema student, both.’

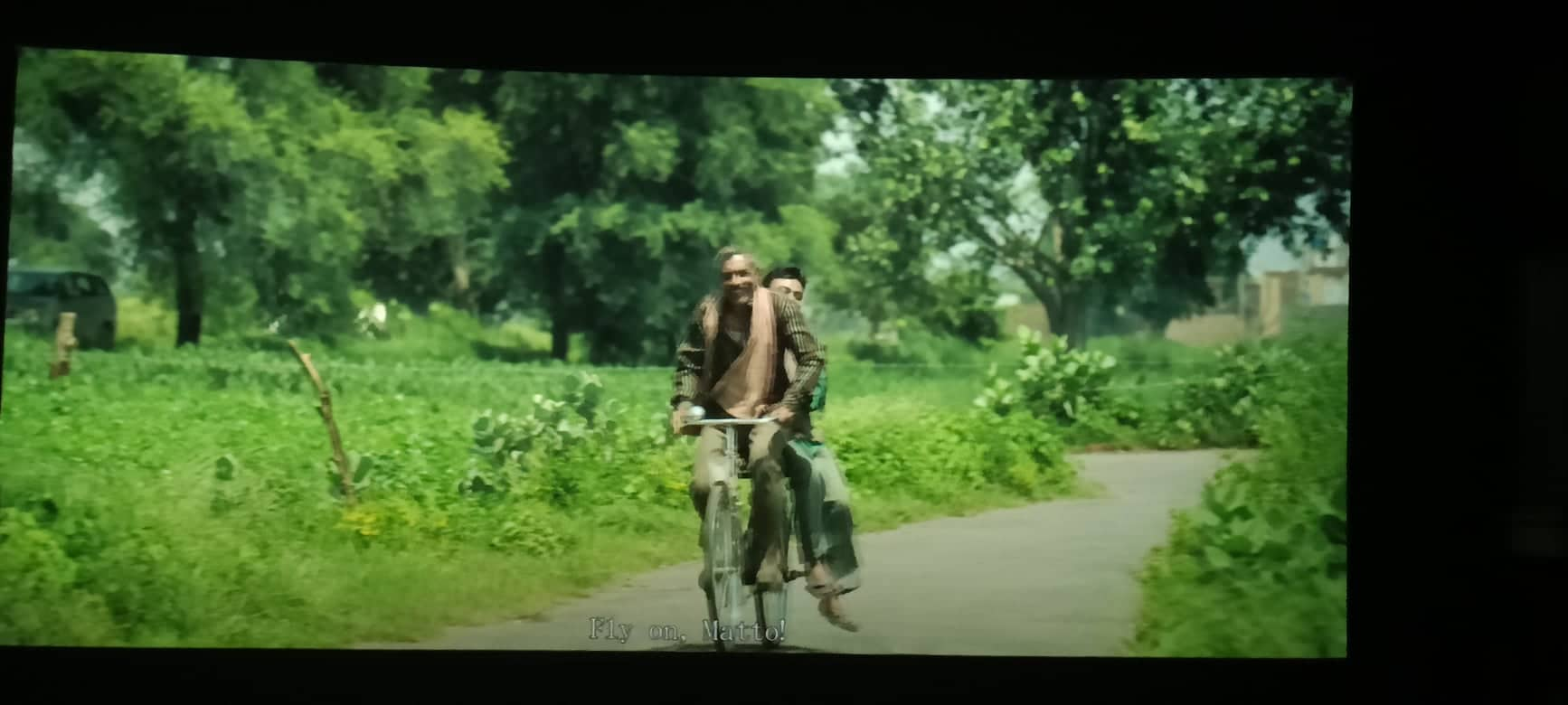

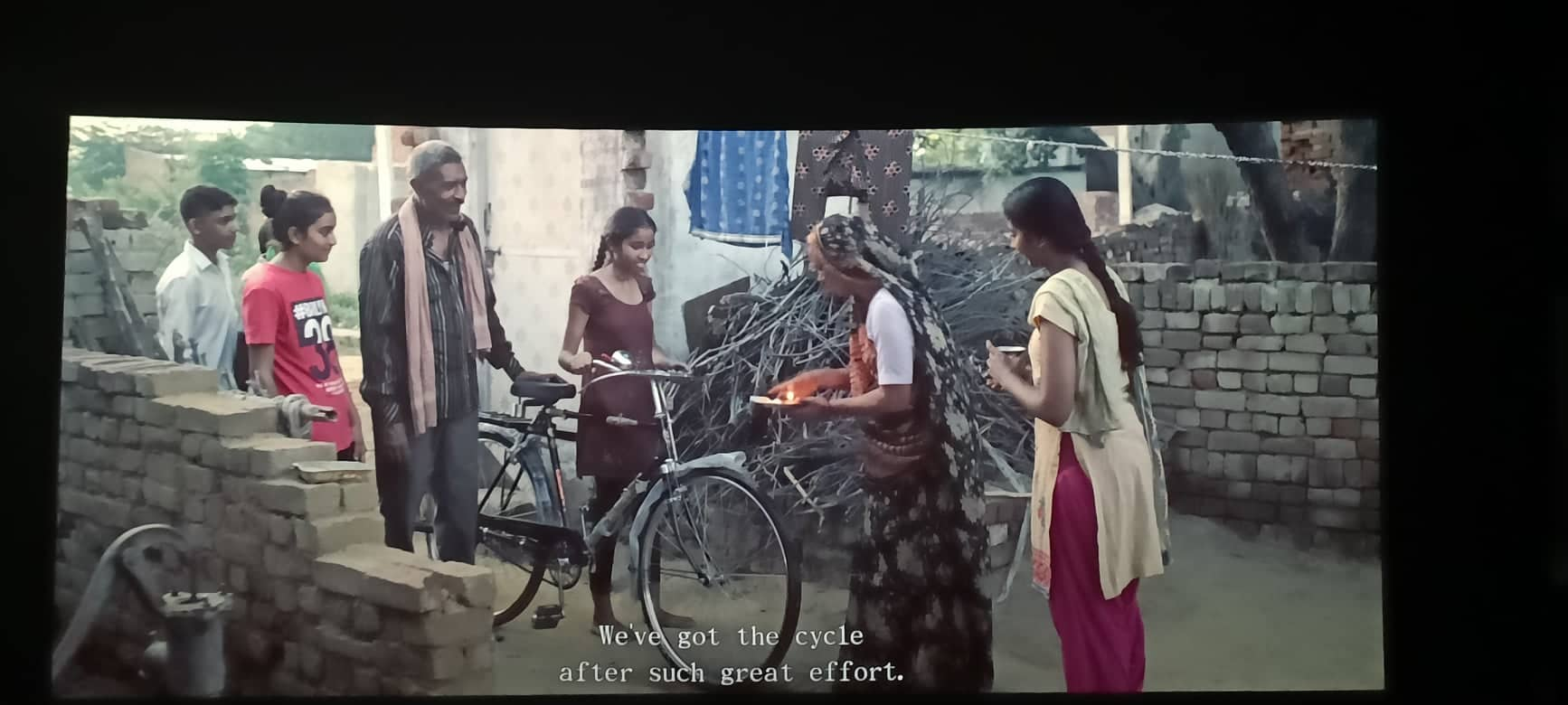

[caption id="attachment_447099" align="aligncenter" width="1734"] Screen Grabs from the film, 2022, Photos by Aatika S[/caption]

Screen Grabs from the film, 2022, Photos by Aatika S[/caption]

Matto Ki Saikil foregrounds one similar small-town story of Mahipal Matto, played by Prakash Jha, whose coveted dream is to own a cycle. A daily wage earner, his struggle drives the narrative. His house remains a constant site of grit and impoverishment. His friends and family all eagerly await the arrival of the cycle yet there’s no hope.

Pulkit says, ‘In 2014, M. Gani came up with the idea and told me to write a script. I was very young at that time. I had not seen villages and had an idealistic understanding. So, I befriended Teekam, who lived in a nearby village in Mathura. I spent two months with him. That became the research for the film. I met construction laborers, upper-caste brats, and other people. The realism of the film comes up from here. The dialogues, for which many critics have praised me, have developed from these experiences. I learned many new idioms and proverbs with them. In 2015, Prakash Jha read the script and agreed to make it. It has only been an upward journey from there.’

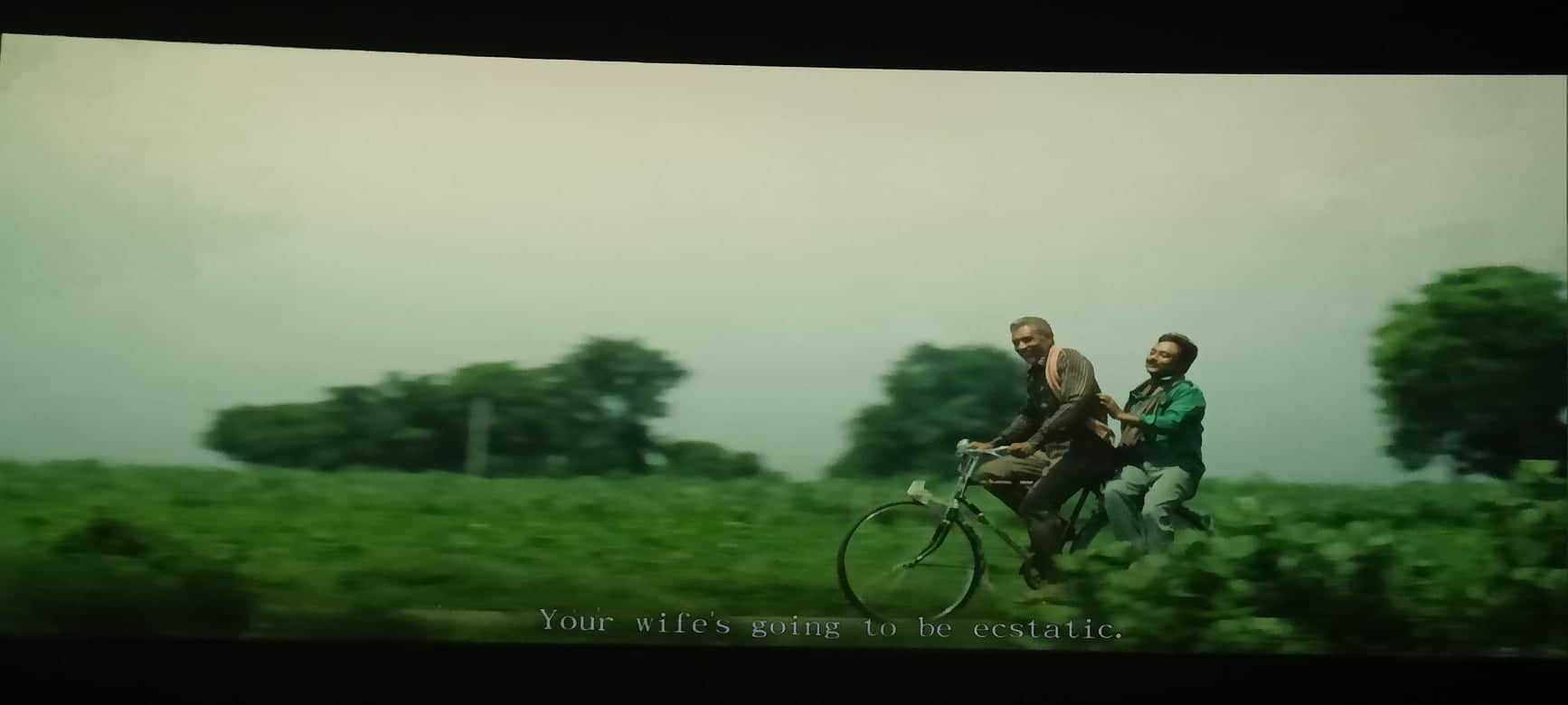

[caption id="attachment_447100" align="aligncenter" width="1734"] Screen Grabs from the film, 2022, Photos by Aatika S[/caption]

Screen Grabs from the film, 2022, Photos by Aatika S[/caption]

I ask him about the peculiar name inscribed outside Matto’s humble abode. He says, ‘The government introduced a scheme that poor villagers will be provided with a toilet in their homes. Those toilets were named Ijjat Ghar. The idea was that ghar ki izzat ghar mein hi rahegi. But Matto and his family never use the toilet as most of these don't have a proper sewage system.’ Indeed, every morning Matto goes to the farmlands to relieve himself and yet is unable to under the watchful eyes of the officials!

In many similar ways, Matto’s every day journey overshadows the film. It is his labor, dreams, and story that form the main issue. The portrayal of the female characters remains tokenistic. To this, Pulkit says, ‘Matto's dialogues are his way of seeing things. His wife, Devki, doesn't succumb to him and rebels. She, I would say is a powerful character in comparison to what would be expected of a wife in a north Indian village. However, it is also true that the film doesn’t adequately address the issue of lesser screen time and no character nuance or representation of the labor of Dalit women.’

The film does succeed in highlighting the everyday gendered and casteist reality of Indian villages, though through its songs and dialogues. For Matto and his male friends, the cycle is a female heroine to be mounted upon and ridden every day.

Pulkit says, ‘The conversations when Matto has got a new bicycle and is working with other laborers–they tell him to do the construction work fast as the wife must be waiting. This is said with a subtle sexual undertone. These things were deliberately done to highlight the ingrained patriarchy among the oppressed class. In some films, the oppressed class is seen as pure and crystal. But it's different in everyday life. The casual sexism was hence deliberately placed.’

Pulkit further talks about the depiction of caste in the film. ‘Whenever I used to cross the labour chowk, I felt a sense of shame and anger. Then, this script happened which is about a construction laborer. The director and I were sure that there has to be a scene about the labor chowk.’ Additionally, ‘Rajesh's character, who is a Dalit lawyer, is inspired by a real person, who is also into the business of pig rearing. When he started practicing law, he didn't get clients as he didn't have the social connections that an upper-caste lawyer would have. And even if he got clients, if they came to know about his caste, they would never return to him. We immediately decided to have one such character in our film. We felt his voice must be heard.’

As the film progresses it strips naked the village as a den of ignorance and oppression. There is no romantic nostalgia for the rural homeland. Matto is caught in the perpetual cycle of marginality and so is the next generation.

The stark end is deliberate, remarks Pulkit. ‘We spent months layering this film with the politics of everyday life. We wanted to emphasize how every mundane conversation is political. Be it the politics of caste or the so-called development or gender politics. The theft of the bicycle in the end was placed so that Matto comes in direct conflict with the system. Till then, the system is suppressing him, but Matto is never in conflict with it. He almost accepts everything. But the theft makes him angry. The film could have taken many other shapes however this is my first film. I intend to only improve in my upcoming work.’

(Aatika S is a fellow at the SEEDS-TCN mentorship program.)