A conversation with GN Saibaba’s wife AS Vasantha Kumari

In a conversation with TwoCircles.net, the wife of jailed scholar-activist GN Saibaba AS Vasantha Kumari talks about his new book, the situation of prisoners in jails and her hopes and dreams.

Aatika S | TwoCircles.net

I still stubbornly refuse to die

The sad thing is that

They don't know how to kill me

because I love so much

The sound of growing grass

— GN Saibaba, Why Do You Fear My Way So Much-Poems and Letters from Prison

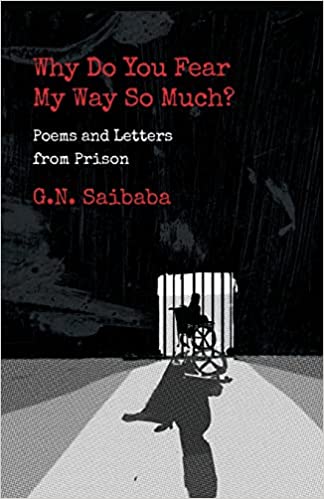

NEW DELHI — I first met AS Vasantha Kumari on the evening of May 4 this year. She had come to Jawahar Bhawan in Delhi along with friends, comrades, workers and students of her partner GN Saibaba, the jailed activist-scholar. The evening was a heavy one as a wide variety of emotions filled the air. There was remorse but also a strong feeling of solidarity amidst us. The gathering was to mark the launch of Saibaba’s book Why Do You Fear My Way So Much-Poems and Letters from Prison.

Professor Saibaba has been imprisoned in the Anda cell of Nagpur jail since May 2014 under the draconian anti-terror law Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA). He was sentenced to life imprisonment in March 2017. Vasantha, Saibaba and their friends have exchanged several letters and poetry since his arrest, which have been compiled in the form of this book. The letters are difficult to read. They are marked by an overpowering sorrow, helplessness and repression. The poetry is annotated with everyday incidents of longing, separation and grief. The communication yet remains steadfastly bound by a sense of strength, hope and love.

Vasantha spoke to the small yet diverse audience gathered that day before the book launch. She recollected her first meeting with Sai and their years of growing up together while teaching each other Maths, English and literature. Her quivering voice betrayed her strength and passion as she recounted all those years of struggle and solitude. She narrated incidents of love from their life and how the companionship shaped her intellect. There were moments of every hue — fun, laughter, gravity and misery. Her indomitable spirit was remarkably visible that evening. She spoke of Saibaba’s mass struggles and social movements, the fight for reservation, and other similar lifelong battles. The other speakers, Meena Kandasamy, D. Raja and Arundhati Roy nodded in agreement to Vasantha’s tale of grit.

She writes in the book, “It was the strength of what you wrote and the intellect that carried you across the world.” The affectionate sentence reminds one of all the political prisoners currently under incarceration for no criminal fault or evidence.

[caption id="attachment_446943" align="aligncenter" width="324"] Cover page of GN Saibaba's new book[/caption]

Cover page of GN Saibaba's new book[/caption]

Over a conversation, Vasantha told me that the book is an expression of Sai’s communication with all of them in the form of letters written from prison. Her voice is in despair with a palpable sense of trauma. We struggle with the language yet find our way to each other through a shared understanding of grief. She told me that Saibaba never wrote much poetry before his painful incarceration. She is fluent with words that must have been repeated frequently over these years— incarceration, poetry, draconian, innocent, distance. The list is long.

At this point, I try to conjure her, the colour of her saree, the shape of her room, the plants outside, and her evergreen smile. She reminds me of many women I know with similar characteristics. She remembers each ache surrounding Saibaba and enlists them. She questions how he spends his day worrying about his health, feelings and the inability to express. It seems an insurmountable challenge to just see two individuals talk and meet each other without any restrictions. At one point in the book, Saibaba concurs, “I live in your dreams awaiting your letter.”

Saibaba’s hope is infectious, she remarks, especially in the current times of distress and depression. She also remembers how the book launch was full of new youthful faces. His absence is surmounted by more people joining the cause of his release. Although the need for a larger dialogue on the rights of political prisoners, violation of human rights and international laws, abolition of prison, and the issue of everyday injustice looms large over the conversation.

As we continue to talk, she says that her experience fighting the state, judiciary and the police can form another book in itself. Her unique subjectivity emerges at such high points in the conversation. I feel glad to have received a peek into her own life. Yet we both hesitate at moments of abject pain and oppression that both of them have been subjected to along with their family. Vasantha inevitably recounts the horror of Saibaba’s arbitrary arrest and his daily struggle with disability. “I have to suppress these emotions and fight for his release. The struggle is even for minor facilities like medicine, water bottle, books, etc,” she told me.

Vasantha’s fight is reflective of larger socio-political issues governing the country. She was not allowed to meet Saibaba on her first mulaqat (visit) to the prison as she didn’t share his surname. Hence, the prison guards refused to believe her as the wife. I remember a line from the book, “…now the times are so rigid and murky that the word ‘love’ has been enlisted as a crime.”

She talked about how prisons are filled with people who have no understanding of the legal system. “What my experience has taught me is that the fight should be for everyone’s release, along with the implementation of progressive laws for political prisoners and the repeal of all repressive laws,” she said.

GN Saibaba was given life imprisonment along with six others, out of which three are Adivasis and the other two are the journalist Prashant Rahi along with the former JNU student Hem Mishra. Vasantha told me about the nameless three co-accused Adivasis: Mahesh Tirkey, Vijay Tirkey and Pandu Narote for whom no committee, book or conversation has taken place.

Narote passed away on August 25 this year due to swine flu and the consequent non-availability of treatment and negligence of the jail authorities as well the state government. “But who remembers Pandu Narote,” she asks. Her memory is filled with many other custodial deaths of marginalized persons.

“We need to move beyond Saibaba as the fight cannot be confined to any one individual. The fight is for all of us to implement the constitutional rights for the sake of equality,” she said.

The book talks about the increasing inability of Saibaba to write, coming down to less than a page per week. Yet at the same time, Vasantha has been trying to concentrate and write to compensate for the non-availability of information about Saibaba.

She has also been trying for better legal coordination and building a larger human rights defence. Besides writing on daily issues for Telegu magazines, she also does part-time work to sustain herself.

“I don’t remember earlier how the days just flew by with Sai at my side. Now, I feel stressed and sadness but I also try to be hopeful. Pandu’s untimely demise depressed me for days. So did the death of Kanchan Nanaware.” She lamented the injustice perpetrated against journalists, human rights defenders, academicians, intellectuals, poets, writers, and cultural activists in the country under the garb of law and order.

I ask her about her message of solidarity to the friends and family of other political prisoners. Vasantha corrects me and says that her message is for all innocent prisoners and not just political prisoners. “We cannot lose in front of oppression. We have to keep hope alive in ourselves and continue to fight together. Our task is to instil faith in others and pave a way for a larger struggle. We have to carry the spirit of our incarcerated friends with us and continue the battle,” she said.

She stressed the need to resort to democratic methods to fight the injustices of the state.

“UAPA along with other anti-terror laws and the various prison manuals have been continuing since the colonial era,” she remarks. “Prisons cannot be torture cells since their purpose is rehabilitation. Compared to political prisoners, politicians get parole and bail and all the other facilities as well. Justice Krishna Iyer also stated, ‘Bail is the rule and jail is the exception.’”

She continues, “Today 80% of undertrials in Indian jails continue to perish in extremely exploitative conditions, most of them hailing from marginalised backgrounds. The Covid-19 induced pandemic only made the situation worse.”

The next day she shares a message about a press conference from Sanjeeda, wife of Atikur Rahman. The tone is clear that the battle is long. As she waits for the release of GN Saibaba and other prisoners, Vasantha is yet to receive all of his letters and poems. As the book launch culminated, it began pouring. The miserable heat of the day was drenched within seconds. Our hope is likewise. As Kabir says, "He’s a messenger of love for people, Why do you fear my way so much?"

Aatika S is a fellow at SEEDS-TCN Mentorship Program.