By Inder Bisht, TwoCircles.net

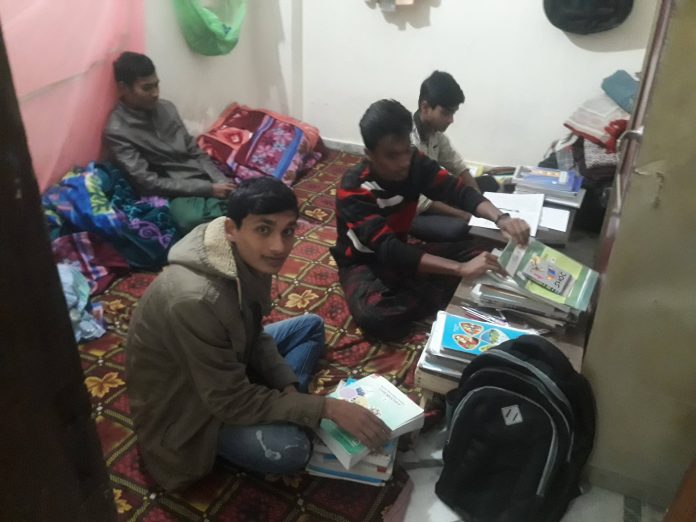

For the last one year, the three Rohingya teenagers along with seven other community members have been living in a two-BHK apartment in Delhi’s congested Jamia Nagar under the Hostel Literacy Project, run by 23-year-old Ali Johar, a fellow Rohingya.

Handpicked out of hundreds of schoolgoing Rohingya children from around the country, these boys stand a much better chance to clear their exams compared to their peers in the refugee camps thanks to the efforts of Johar. The food, transportation, and stationery expenses at the hostel are borne by Johar through donations from sponsors.

“The hostel provides an encouraging environment to study which we often lack in a refugee camp,” says Saifful. The brunt of forced migration from Myanmar has been felt by Rohingya children who have lost the opportunity to be educated.

“Those Rohingya children who finished their primary education in Myanmar are facing difficulty in adjusting to Indian education system due to a different language of instruction and also because education here is more advanced than Myanmar,” says Zohar.

“Only 25 Rohingya children study in ninth and tenth standards in India while only 13 students are studying in 12th standard in India,” says Johar, adding, “Only two Rohingyas are presently studying in Indian colleges.”

Around 20,000 Rohingya are currently living in India according to the UNHCR while the government pegs the number higher. The students staying in the hostel in Jamia Nagar had little hope of a good future until about a year ago, but now they dream of a respectable profession in India or in their native country after finishing their graduation.

Some of the students are interested in starting their own business while others want to become doctors. One of the students wants to become a journalist to better represent his community’s issues.

“Often, other people raise the issues of our community. I think that someone from the community can highlight its problems in a better way,” says 17-year-old Hussain.

A quiet and shy science student, Fayyaz, 18, is all geared up for his Board exams scheduled for later this year for which he also takes private tuition in Physics. After some persuasion, he opened up about his life and said that he had arrived in Hyderabad from Myanmar in 2017 after his village Renohali was engulfed in ethnic violence.

He worked in Hyderabad as a waiter initially and then tried to enrol in the local schools. However, due to insufficient documents, he couldn’t get admission in the 11th standard.

One day, Fayaz heard about the hostel programme for Rohingya students in Delhi which promised free accommodation. He applied for it and got selected.

“Earlier, I used to just hope to survive somehow but thanks to this hostel now I can dream of achieving my goal of becoming a doctor,” says Fayaz. The idea to start the hostel struck to Johar in 2015 when he was working as an interpreter at the UNHCR office in Delhi.

“We did a survey of our community children in India and found out that only two of them were going to school for secondary education although around 80 such children had completed their primary education in Myanmar,” says Johar.

First, they opened a hostel in Vikaspuri in 2016 however due to financial constraint it had to be shut after three months.

Then Johar met a person at a refugee camp while he was donating food packets to the people.

“I asked him to help the Rohingya children for their education as education would last longer than food packets. Convinced by my argument, he gave one of his apartments to us to move in,” said Johar.

Shortly after, an NGO came forward and offered to take care of the grocery bills of the hostel. Johar then crowd-sourced the funds for transportation, stationary and other expenses to run the hostel with the help of students from St. Stephens College, Delhi, and from Jindal and Ashoka University in December 2017 and successfully managed the hostel for one year.

In January 2019, however, the NGO which had been providing funds for grocery items for the hostel backed out citing a dearth of funds causing uncertainty over the future of the hostel and its residents. “The students are preparing for their annual exam in April but we have funds for this month only. I am worried if I don’t manage to collect the money all the efforts of us could go to waste,” Johar rues.

Most of the Rohingya children in India have enrolled into National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS) where classes take place during the weekend. However, due to their financial condition, they are unable to afford tuition classes and clear their exams.

In Delhi, a non-profit-organisation Don Bosca in partnership with UNHCR runs five-day-a-week tuition classes for refugee students which the Rohingya students term crucial to clear their annual exams.

However, the classes are held only in the national capital leaving the refugees in other parts of the country in a disadvantageous position.

In the absence of a proper educational framework for the children of Rohingya refugees in India, thousands of children fritter away into child labour with few of them are even gravitating towards criminal activities in the absence of proper guidance and opportunities.

“A 16-17-year-old teenager who has studied only till fifth or sixth standard in Myanmar and is unable to study in India has nothing else to do but to work as a labourer or rag-picker here. We have noticed that some of these kids have become drug addicts and commit petty crimes like pick-pocketing and theft to sustain their addiction,” says Johar.