By Abdul Basith, TwoCircles.net,

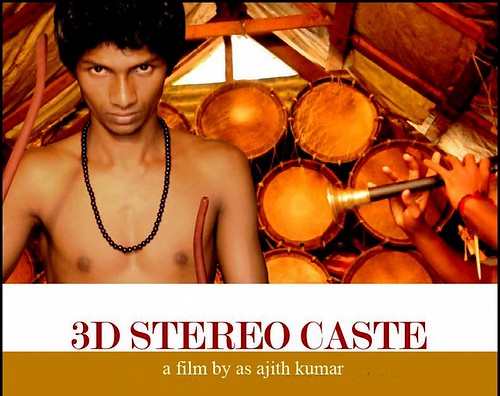

Kozhikode: 3D-Stereo Caste – a video documentary by AS Ajith Kumar on the caste discriminations prevalent in the musical arena of Kerala, is an advanced form of resistance against the mainstream mediated stereotyping of lower caste music.

“Unlike earlier documentaries which handled this topic, it is not all about putting forward a claim with regards to the glorious past of lower caste music and instead emphasises on reinventing these musical forms in the modern context”, says DR K.Satyanarayana (Associate Professor ,Cultural Studies department,EFLU, Hyderabad).

Director AS Ajith Kumar interacting with the audience after screening organised by Other Books at Nalanda auditorium, Kozhikode [Photo Courtesy: Abid Aboobacker]

The documentary has been screened in universities and colleges throughout Kerala, Bangaluru, EFLU Hyderabad, University of Hyderabad, among others.

Most audience shared an opinion that no other documentaries handling similar Dalit issues had this critical energy the documentary possessed. The documentary is a three part video covering the field of Chenda (a drum like percussion instrument), cinematic dance and folk music performances.

Speaking to TCN Ajith Kumar said, “My documentary is not all about addressing the discriminations against low castes, their music and art and instead it is about the politics of classification of music, politics in the sound and the body movements and the politics of the place where these low caste art forms have their roots based and are found flourishing.”

Promotional still from the documentary featuring Praseetha

“The ‘classical’ music discourses asks you to control your body and voice ,it tries to separate the voice from the body, it prevents you from shaking your body while singing; but in Dalit music, body and voice are not separated. They dance while they sing, they are loud and full of energy. So my documentary is about the politics of sound as well” says Ajith.

He adds, “We chose Chenkal Choola of Thiruvananthapuram district as venue for the premiere because this was a place where a lot of artists, singers, drummers, dancers and ganamela artists came up but went unacknowledged in the musical map of Kerala.”

The boys here, love playing football and they are part of film star fans associations but these colony has been a victim of the mainstream branding that such colonies inhabited by the lower castes, lacks culture and is a haven for drug addicts, drunkards and other anti-social elements.

Shots at Chenkal Choola are intentional attempts to break these types of mainstream branding regarding Dalit colonies, by focussing on their art, music and passion, he informs.

The mainstream considers Mylapore and Thanjavur as divine places because they are the hubs of classical music like Karnatic whereas Chenkal Choola has a “polluted” image because it disturbs many elite class minds, being the haven of Dalit music and cinematic dance, says the Director.

So Ajith’s documentary is all about smashing many prisons erected by the vested interests within the still prevailing caste hierarchy in Kerala, which injects elite class art forms as mainstream through their influence in musical/art institutions like Kalamandalam and by even influencing the program organising and judging panels of govt organised school youth fests.

Nideesh, a documentary character and drum percussionist at Chenkal Choola

Ajith says that the high bass/volume music in the low caste majority areas have a politics to put forward and it is the same politics that works out with regard to the percussion instrument ‘chenda’ (drums).

The Shinkari melam performed with a high volume, bass and energy by low castes using drums is considered a secondary type of percussion music compared to the Panchari melam which finds acceptance in temples and school youth fests. Though Shinkari melam is allowed in school fests, none until now in the history of school youth festivals were neither given ‘A’ grades on performing it nor were they allowed entering the temple premises.

The documentary features a boy named Nideesh hailing from Chenkal Choola region of Thiruvananthapuram district. Though he belonged to a lower caste, he got admitted into the Kalamandalam. He was, however, forced to abandon the ‘elite’ institution as he couldn’t withstand the harassments. Nideesh thus was a victim of humiliation than discrimination.

But he contested in the school youth fest this time and scored ‘A’ grade. This was a sweet revenge for him because he turned successful in the very same category and place from where he was once forced to elope.

He got ‘A’ grade because he was able to learn and perform Panchari melam (the elite class drum percussion), the school youth fest manual mentions that the contesting item is ‘Chenda melam’ (drum percussion) and it is an unwritten law that Shinkari melam (the low caste drum percussion) will not be awarded good grades.

3D Stereo Caste Promo featuring Nideesh

It is because of this unwritten law and prejudiced approach that around 19 teams who contested the Chenda melam chose Panchari melam over Shinkari melam in the last school youth fest, notes the documentarian who is a musician himself.

The low caste drum percussionists, folk singers and cinematic dancers featured in this documentary wears jeans and other trendy casuals while performing; their agile and vibrant moves while dancing for cinematic songs and performing folk songs are quite capable of putting forward a question, which music/art form actually deserves to be called by the name main stream?

Is it the institutionalised elite class Karnatic music, traditional upper class dance forms like Kadhakali, Mohiniyattam, Bharathanatyam, insistent on regulating a performer/audience with clear cut restrictions on how to even tap his fingers and often ends up boring for most? Or is it the folk songs, shinkari melam (high bass drum percussion mostly performed by lower castes) and vibrant moves in a cinematic dance which enables the celebration of ones body to its full?

The director feels that cinematic dance is very well represented by the lower castes and it doesn’t prevent anyone from performing or excelling in it, citing nasty reasons like ‘keeping up the divine aspects of art or music’ and none dare to regulate the performers saying that it should be sung this way or that way.

Interaction with director at EFLU Hyderabad

Men or women who has a passion for it can perform cinematic dance and it is this equality in the opportunities, which resulted in the exemption of this widely accepted art form from the school youth festivals. Most schools ‘brain washed’ by the elite class interests too take care to associate cinematic dance as something vulgar whereas the fact is that it is the art forms like Kuchipudi, Bharathanatyam and Mohiniyattam having vulgar postures while being performed.

Even when the mainstream accommodates Dalit music or folk song, it is like a few people have vested interests in attributing tradition, age old costumes etc to these lower caste art forms thus conveying a message that their lives are still primitive and secluded from the mainstream.

This documentary is a major step in overcoming such agendas against folk songs and lower caste music as it features men and women wearing trendy costumes; innovating folk songs and their dancing steps to meet the tastes of the present day audience, not quite insistent on clinching on to the past.

This indeed is a major resistance because the elite class traditional art forms are losing their grounds clinching on to the past and thus turning out dated before the audience and their only zones of survival are school fests and such governmental programs where they are successful in giving an impression that, these art forms are very much inherent to the Kerala culture.

This is the reason, why they want folk songs and Dalit music too to stay the way it has been for centuries. They fear the Dalit artists coming up with fast numbers, wearing attractive costumes, interacting with the audience while performing folk songs and thus reinventing the lower caste music to fit the needs of the modern context.

The elite class hence insists on preserving the tradition of folk songs and Dalit music, which actually is out of the fear of losing the supremacy of their art forms than out of sheer love for the lower caste art forms, and the documentary is a sophisticated form of resistance against mainstream agendas on this regard.

The energy conveyed through these Dalit musical/art forms as portrayed in this documentary is quite capable of challenging the dominant discourses on music and those elite class cultural spaces associated with it.

Praseetha, a folk singer featured in the documentary, rightly says, “Folk songs always have a story, an idea and politics; If we can convey that politics precisely through our eyes, voice and the body, that ensures success of the song, the singer and the performance.”