“Even if 100 people from my community of scavengers exit from this inhumane occupation and move towards a dignified life, I will feel my efforts have borne fruits.”

By Yogesh Maitreya, TwoCircles.net

Mumbai: Sunil Yadav was born and brought up in Mumbai. The area of Mahalaxmi (Saat Rasta) where he grew was, nay to some extent still is, notorious for drug pushers, liquor addicts, gang-wars, violence and lots of conflicts.

Yadav’s father, who worked as a manual scavenger with the Bombay Municipal Corporation (BMC), was a liquor addict too. “In such a hopeless atmosphere, my mother wanted me to study. Babasaheb Ambedkar’s movement had a great impact on the lives of people, literate or not. Yet I did not know much about Ambedkar, caste and related issues till I was 25,” Yadav recalls.

Yadav’s three generations have been into manual scavenging, all working with BMC. His parents were barely educated. And Yadav too had failed in class 10, after which his life took a flight away from education. No education meant he went on to work. “There was no one for guidance, who could have shaped my quest for a dignified life,” he shares.

Yadav, today 36-year-old, had just crossed 14 when he started working. He travelled across the state with almost 300 kgs of bundles of paper. “I was healthy and strongly built, so I did not find it has difficult work.” Changing jobs, Yadav went on to become a security guard, an office boy and also worked at a wine shop.

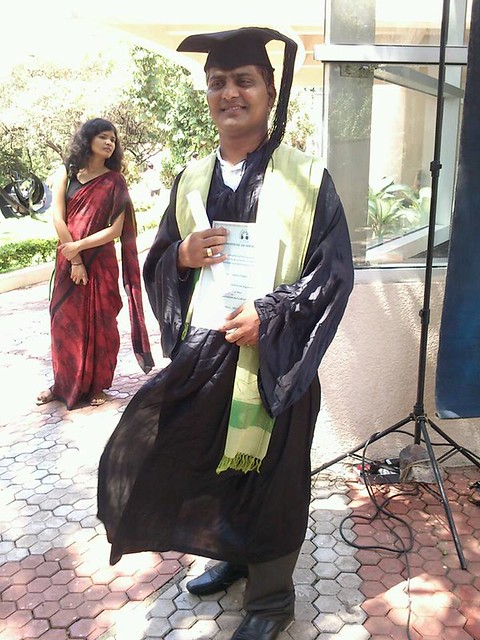

So how did he manage to get through the premier social sciences institute such as Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), passing his Masters and then getting admitted to the M Phil course?

Growing up, Yadav was fond of two things, cricket and reading newspaper. Cricket he could not afford as he could not buy anything for it. But reading he could. “I was reading newspapers. This was how I updated myself about politics, but more importantly about the violence of atrocities. In fact, this had helped me getting admission into the Yashwantrao Chavan Maharashtra Open University (YCMOU) from which I graduated.”

Before that in 2005, his father’s liquor habit led to trouble he created even during work. Around the same time, his father got ill, he also suffered paralysis and was admitted to a hospital. “When it became sure that he could not work anymore, I got my father’s position at BMC,” Yadav adds.

That was a beginning of a new chapter. Yadav went on to face the system and experience the horrors of the caste. “On the first day, I thought that the work wouldn’t be much difficult. I was assigned the work at ‘house gully’, a narrow place between two buildings in which people put garbage at Grant Road. That day, as I returned home, my entire body was stinking. I was unable to eat because of the horrible stench. My body was aching too. I washed my body several times but the stench did not go,” he shivers even at the thought of that day.

Slowly he got the sense of the system. “I decided to exit from this hell of scavenging. So I somehow managed to find information about open universities and their correspondence course. I got myself admitted into B Com, which I completed in 2008.”

He wanted to study further. He came to know that TISS offered a promising teachings/course in social work. When his search for this kind of course was on, obstacles did not leave him. “For 14 months, I was not given study leave – one of the provision which the BMC gives its employees if they want to study. For 14 months, I studied keeping the rigorous schedule of TISS during the day and worked at night. During this, my health slightly deteriorated since I had to travel a lot, work and also take care of my family responsibilities,” Yadav, the eldest son of the family, says.

But he managed, and managed well. Sunil was also selected for student exchange programme during his MA in TISS and was sent to South African University for three months.

But despite proving his ability for better and dignified life, his struggle with BMC for a better position did not stop. In 2014, there was a walk-in interview at the BMC for the post of ‘Labour Welfare Office (LWO)’. “The panel even refused to take my interview and gave some reason about minute technical detail,” he claimed and added, “I am the first manual scavenger in the 150 years history of BMC who even applied for a study leave. Although I am eligible and deserve better/dignified post now, I had to continue working as a manual scavenger. This is the tragedy with this country.”

Even this adversity did not deter Yadav. He knew, his struggle is much bigger and longer. On the basis of what he achieved, he got admission to the M Phil course at TISS. He still attends his course during day time and works at night.

But there is a positive flipside to his struggle. “People within the BMC, especially scavengers, those who used to mock me about my going to a college and study, now understand the importance of education. In fact, I have helped 27 people – my colleagues – to get admission into various correspondence courses.”

His wife too is studying now, pursuing law and his brother is also studying. Although Yadav is clear that he still has a lot to struggle ahead, yet he is optimistic. “Even if 100 people from my community of scavengers exit from this inhumane occupation and move towards a dignified life, I will feel my efforts have borne fruits.”

Yadav is now planning doctoral study and then a post-doctorate too, aiming to work on the issues of women manual scavengers.