By Somnath Mukherji,

Rajkunwar’s Gond’s slender frame looks taller than the actual 5 feet 4 inches she measures. This is because she is light. Very light. Exactly 31Kg and 700gm. Ten days ago she was only 31Kg. She was sliding down a steep slope in her forest village of Katami in Bilaspur district of Chhattisgarh. Noticing her condition, the village level healthworker of Jan Swasthya Sahayog (JSS) immediately took Rajkunwar to the nearby JSS subcenter in Bahmni where she was diagnosed with Tuberculosis beyond reasonable doubt but was sent to JSS rural hospital in Ganiyari, a 2 hour ride over some rough roads for more confirmatory tests and treatment.

Rajkunwar and her husband are landless and earn their living through agricultural labour and the few days of work that is available through MGNREGA. I followed Reena, a social worker with JSS, who was visiting Rajkunwar in her home to follow up. Home visit! Had it not been JSS explicit aim to reach out to the most marginalized, about 55 forest villages in this area would not have expected any access to healthcare, much less a home visit. In the early days of the sickness, Rajkunwar had gone to a Jholachaap (quack) who treated her for malaria and gave a bottle of saline intravenously. Five hundred Rupees of their hard earned money was wasted!

Reena located the home at the edge of the village overlooking a valley where the river was reduced to a trickle in this winter month. Bright yellow fields of mustard swayed in the gentle breeze in the small valley. It is hard to imagine such beauty can coexist with the cruel deprivation that Rajkunwar’s family lives with – 1.5 Kg of rice and 500g of potatoes is the average daily diet of this family of 5 adults. The death of 2 grandchildren in the recent past adds to the heaviness inside their home.

As we settled in the courtyard, Rajkunwar briefly disappeared into a room and brought out a plastic bag with substantial number of medicines in them. At Reena’s urging, she began explaining which medications she has been taking and at what time of the day. The drugs are aptly colour-coded and the time when they should be taken is marked on a small paper with the position of the sun indicating the time of the day. Really? Can modern healthcare be made so poor-friendly? Can socio-economic status and the cultural context play such an important role in taking healthcare to the marginalized people of India?

The first thing that strikes a visitor to JSS is the respect and compassion with which a poor person (or any person for that matter) is treated – for human dignity should not have to calibrate itself to appearances, economic backgrounds, and the ability to read. What makes the efforts of JSS unique is not its medical expertise alone, but its ability to read the pulse of a society. In JSS, modern science has not been able to induce contempt for a people living with a different worldview. JSS puts significant efforts in improving agriculture, in developing technology appropriate for the region and people, in understanding social processes that lead to illnesses. JSS operates with about 100 village level health workers centered around 3 remote sub-centres that are finally backed by the rural hospital in Ganiyari with the capacity to perform complex surgeries and an in-patient facility of 60 beds. Ambulances travel daily to the subcenters and one is stationed in Bahmni, the furthest sub-centre, at night for any emergency.

“Your urine might turn red due to the medication,” Reena patiently explained Rajkunwar sitting on her haunches, “But do not be alarmed. Don’t stop taking the medicines. You have to continue them for 9 months to get well completely”.

Rajkunwar reported a slightly improved appetite which was corroborated by the marginal increase in her weight; marginal yet trend-reversing. Her BMI is a precarious 11.8 (<18.5 is considered to be a state of chronic undernourishment). Reena wamted to see the bag of 2kg Kala Chana (Black Gram) that is given to TB patients on a monthly basis as protein supplement. Barely 100gms were left – it had just been 7 days. Reena understands that even in her condition it is not possible for Rajkunwar to eat the Chana by herself.

Rajkunwar being accompanied to the sub-centre

“How do you feel?”

“Not too well. I am still very weak to do any work at home,” Rajkunwar says.

Ill-health steals the most precious belonging of the poor – their capacity to labour.

“Come with us to the Bahmni sub-centre, the doctor is here today. We will bring you back to the road in a vehicle,” Reena tries to persuade Rajkunwar.

The Bahmni sub-centre is a miracle of appropriate technology that defies all limitations of remoteness from urban centres. It is completely powered by solar energy including a refrigerator to store anti-venom and other emergency medicines, UV purified drinking water, WLL phone, and is staffed round the clock by a senior healthworker. On Tuesdays a doctor from Ganiyari is here and so is a mobile diagnostic laboratory that can turn around blood, urine and sputum samples the same day. Most importantly, the adivasis don’t feel out of place at Bahmni sub-centre.

Sub-centre at Bahmni

Rajkunwar like a large percentage of the people who come to JSS will not have to pay anything, but her care will be determined by her condition alone and nothing else. Others pay a very nominal fee. In 2010 JSS treated 470 cases of TB which increased to 587 in 2012.

Dr Ramani talks to Rajkunwar while Sr. healthworker Santosh examines another patient

If the message of JSS is not understood, the poor will continue to be deprived of rational healthcare while the rich will be sick of hospitals.

Some More Examples of App. Technology at JSS

Baby sized sleeping bags: To save newborns from hypothermia in the mountain villages. The bag has a pocket where a big packet of palm oil can be heated in boiling water and inserted for additional heat.

Handwashing station for village homes: The plastic pipe is fitted with an iron strip which when lifted is held by the magnet eliminating the need for a tap.

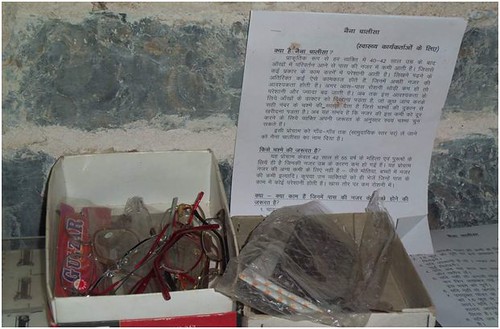

Naina Chalisa: A set of reading glasses over a range of power from which villagers can choose on their own without having to go to an ophthalmologist. This has been very popular with the people.

UV filter for drinking water: The lid for a 20 litre steel container is fitted with a UV lamp which can run either on 220V AC or 15V DC from solar power.

—–

Somnath Mukherji is a volunteer with Association for India’s Development (http://www.aidindia.org )